In the fashion industry a second is an item with a few defects that can still be worn or used. If there are seconds, then there are firsts though we don't call them that. We may call them first quality, though I rarely hear that term either. The word quality, all by itself, is a controversial term with various meanings attached to it. If there are firsts and seconds, then there are also thirds.

The goal of any company is to produce goods without any defects for the least amount of money possible. But as we all live in the real world, defects happen. I've worked for three different companies and how each handled defects were roughly the same. Each company came up with a ranking system to evaluate product during production and as it came off the line. Each ranking was called something a little different though they conveyed the same meaning. The qualification for each ranking varied and the product that fell into each ranking was handled differently. Here is a brief break down.

First - top quality goods with no obvious defects

Second - goods with X number of defects that may or may not be repaired, but still wearable or usable and can be sold on a secondary market.

Third - goods with sufficient number of serious defects to render the item unwearable or usable. These goods may be sold for scrap and may be called rejects.

Quality can be subjective and that can cause problems not only in production but in the retail sector. A first quality item can be rendered second or third after it's first wearing and washing. In that case, was the item truly a first quality item? Perhaps not. Likewise, a second can be repaired sufficiently to make it a first quality item. But is it financially feasible to repair a second to make it a first? These are all questions that individual companies must deal with as they develop and sell product. In order to not get too long-winded on this subject, let's look at something I recently purchased at the thrift store.

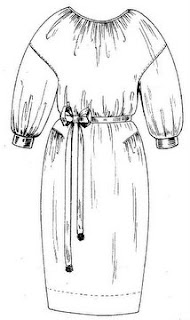

This is a cute knit top that I found at a thrift store for a few dollars. It looked pretty good when I tried it on in the dressing room, but as usual the lighting was bad and I missed some obvious problems. Once home I tried it on again and immediately saw a problem with the gathers on the neckband. I also noticed the brand label and content tag were off center. Also the elastic on one of the sleeve hems was pulling away. It is true that most thrift store clothes are previously worn and I have no doubt this shirt fit that category. But because of the defects, I think this shirt started life as a second and was likely sold at an outlet store or other secondary market.

A closer look reveals the problem on the neckline. There is some fabric caught in the seam. Unfortunately, I did not take any pictures of the problem from the other side, but the fabric caught in the stitching is more obvious.

This style of neckline would be difficult to sew, especially in a factory. First, each gathered area was pre-gathered by applying 1/4 inch clear elastic - stretched between notches. Next, the operator prepares the neck band. The tie and neckband are one piece. The tie portion is sewn and turned out and the rest of the neckband is folded in half. Hopefully there were notches to help the operator position the neck band on the neck, otherwise it would be easy to skew the neckband. Anyway, the operator matches up the neckband to the neckline, starting the sewing on the left side neck. The neckband would be on top and the neckline on bottom. The operator has to match the pre-gathered section from underneath to meet a match point on the band, catch enough of the seam under the

foot securely and then stitch the pre-gathered section to the neckband. Hopefully there is another notch to indicate where the pre-gathered section should end. The sewing continues around the neck to the right side, where there is hopefully another notch to indicate where the next pre-gathered section should start. The neckline is then finished off, overedging the center front neck which is left unattached from the neckband. This small section is later topstitched down. Finally, the next operator would place the brand and size label to the back neck with a single needle machine within the seam allowance of the neckband/neckline.

The most difficult part of this whole sequence of steps would be where the operator starts attaching the neckband on the left side. The pre-gathered section is not stable and will move around as the pieces are placed under the foot. This is what happened here. Some additional fabric worked its way under the foot as the sewing began. The label placement would be difficult because the operator would have to guess where center back is and place the labels on a knit top that likes to move around.

This type of defect would have been difficult to repair in a factory. The elastic and two rows of stitching would be time consuming to undo and redo and look good. The poor placement of the brand labels would have been a second strike. The top was still wearable though and likely sold as a second or at a steep discount. I imagine there were quite a few seconds on this style....

Anyway, I was able to repair this top. I carefully unpicked the band with my fingers crossed that none of the shirt was cut when it was stitched. Luckily it wasn't. I removed some of the elastic in the affected area (it wasn't worth redoing the whole gathered area with the elastic), and regathered the neckline with a needle and thread. I then basted the neckband and neckline together to double check it was all right and stitched it back together. Almost as good as new - at least you can't tell there had ever been a problem.

Showing posts with label Analysis. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Analysis. Show all posts

October 13, 2014

February 25, 2013

A blouse refashion and study

I seem to be a woman obsessed with blouses. Ever since I set out to create a basic blouse pattern for myself, I've kept my eyes open to study many RTW blouses. I've made many purchases from the thrift store with varying types of details and construction. I purchased this blouse a few months ago. As it usually goes, there were many things I liked about this blouse while I tried it on in the fitting room but I did note it was a little too big.

The refashion part of this post is probably the least interesting and so I don't have any before photos. I pulled out my basic blouse pattern and measured across the back at the base of the armholes. I compared that measurement with the blouse and did some math. The blouse needed to come in 1.5 inches on each side seam. Hmmm. The blouse was much bigger than I realized and made me recognize that our perceptions of body shape and size are definitely skewed when in a store fitting room. Anyway, the sleeves are set in flat so I just sewed up each side, taking it in the needed amount.

As I worked on the alterations, I took some construction notes. The front button band is a cut 2 (or 4, 2 for each side). A ruffle is gathered to the band that faces out on the long inner edge. The bands are sewn together on the outside edge and then stitched to the front bodice on the reverse side. The band is then turned to the front and topstitched down. I suspect the ruffle is not pressed down prior to topstitching. I think the operator used the ruffle to pull the band flat, turning the seam allowance to the inside. There is probably some interfacing on the band piece with the ruffle. The whole operation leads to a neat, clean finished button band. The operator who made this is probably very skilled, especially with dealing the bias area near the neck band. Still, this process is easier than it looks.

The only problem with this style is the ruffle. Despite a good ironing with some starch, the ruffle wants to stand up and fall over the buttons. The blouse is still cute, but perhaps a narrower ruffle would solve that problem?

While the sleeves were set in flat, the sleeve cuff was set in the round. The cuff was attached from the reverse side and turned out and topstitched down. I don't believe there was any pre-pressing because you can see the operator used a stripe of the fabric as a guide to turn the seam allowances in. If I were making this, I probably would pre-press just because I don't have the practice. The collar neckband was constructed in the same manner.

The refashion part of this post is probably the least interesting and so I don't have any before photos. I pulled out my basic blouse pattern and measured across the back at the base of the armholes. I compared that measurement with the blouse and did some math. The blouse needed to come in 1.5 inches on each side seam. Hmmm. The blouse was much bigger than I realized and made me recognize that our perceptions of body shape and size are definitely skewed when in a store fitting room. Anyway, the sleeves are set in flat so I just sewed up each side, taking it in the needed amount.

As I worked on the alterations, I took some construction notes. The front button band is a cut 2 (or 4, 2 for each side). A ruffle is gathered to the band that faces out on the long inner edge. The bands are sewn together on the outside edge and then stitched to the front bodice on the reverse side. The band is then turned to the front and topstitched down. I suspect the ruffle is not pressed down prior to topstitching. I think the operator used the ruffle to pull the band flat, turning the seam allowance to the inside. There is probably some interfacing on the band piece with the ruffle. The whole operation leads to a neat, clean finished button band. The operator who made this is probably very skilled, especially with dealing the bias area near the neck band. Still, this process is easier than it looks.

The only problem with this style is the ruffle. Despite a good ironing with some starch, the ruffle wants to stand up and fall over the buttons. The blouse is still cute, but perhaps a narrower ruffle would solve that problem?

December 12, 2011

T-shirt pattern quest pt. 1 : Create a rub-off of an existing t-shirt

My favorite t-shirt company went out of business and I really loved the fit of their t-shirts. The best solution I could come up with was to recreate the pattern by doing a rub-off of one of the t-shirts. This pattern is for my own personal use, but you will find many pattern makers who do rub-offs of existing styles as a starting point. This is one way to study how another pattern maker developed their pattern. I have done this in the industry too, but the resulting style was not an exact copy and bore no resemblance to the initial style. Copying a style in this way for the sake of reproducing an identical product to sell is another thing entirely.

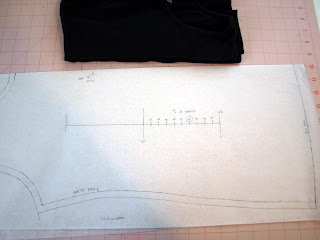

You can see the resulting shape of the pattern that I rubbed-off or traced. The armhole is symmetrical for the front and back bodices, which is fairly typical for t-shirts. Technically, the armhole should be different front to back and if you have fit issues, this would be one place to adjust. For now, I'm leaving it alone.

The original pattern also had binding on the neck and sleeves. I wasn't sure how to accomplish that and have it look neat on a home sewing machine. I think there may be a way that I'll play with later. At this point, I added seam allowances for a narrow neck ribbing.

Patterns for knits are designed with the amount of stretch AND recovery. The original t-shirt had some spandex, which means it stretches and recovers a bit better than a 100% cotton jersey. The original t-shirt is pretty slim fitting because of the spandex and because it is meant as a layering t-shirt to wear under other tops. I wanted to have a pattern I could use with 100% cotton jerseys, so I plan on adding a bit of extra wearing ease.

I noted the amount of stretch for the original knit fabric on the pattern. The stretch ruler is found in the Armstrong pattern drafting book. I'll target my knit fabric shopping for between 50-60% stretch - just have to remember to take a copy of the stretch ruler. I do have some stash knits but it has taken me over a week to find it. More on that later...

You can see the resulting shape of the pattern that I rubbed-off or traced. The armhole is symmetrical for the front and back bodices, which is fairly typical for t-shirts. Technically, the armhole should be different front to back and if you have fit issues, this would be one place to adjust. For now, I'm leaving it alone.

The original pattern also had binding on the neck and sleeves. I wasn't sure how to accomplish that and have it look neat on a home sewing machine. I think there may be a way that I'll play with later. At this point, I added seam allowances for a narrow neck ribbing.

Patterns for knits are designed with the amount of stretch AND recovery. The original t-shirt had some spandex, which means it stretches and recovers a bit better than a 100% cotton jersey. The original t-shirt is pretty slim fitting because of the spandex and because it is meant as a layering t-shirt to wear under other tops. I wanted to have a pattern I could use with 100% cotton jerseys, so I plan on adding a bit of extra wearing ease.

I noted the amount of stretch for the original knit fabric on the pattern. The stretch ruler is found in the Armstrong pattern drafting book. I'll target my knit fabric shopping for between 50-60% stretch - just have to remember to take a copy of the stretch ruler. I do have some stash knits but it has taken me over a week to find it. More on that later...

September 02, 2008

Comparing pattern shaping and children's sizes

As many children's wear designers know, children's clothing has a lot of sizes. It can become quite the dilemma when trying to decide which sizes to offer. Some DE's offer their styles in as many as 21 sizes. Way back in 2006 I suggested a theory to reduce the number of sizes by combining or eliminating some of them. You may want to go back and review the entry Too Many Sizes and other related entries to see how I have arrived at today.

Anyway, I have tried to put the theory into practice and I have made some progress. I only offer my styles in sizes 3M to 6x. I am still working on the grades for the 4-6x styles, so I am nearly there. My sizes break down like this:

3M, 6M, 9M*, 12M, 18M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4

5, 6, 6x

I don't really consider the 9M as a true size. It is a half size between the 6M and 12M and is graded by splitting the grade between the 6M and 12M. The 24M and 2T are essentially the same as are the 4T and 4 - those sizes have been combined for grading purposes. My website still delineates the combined sizes as separate sizes.

This blog entry is not a discussion on the why and wherefores of children's sizing - a surprisingly complex and controversial topic. Instead, I wanted to show a possible grading/pattern problem that shows up now and then. I have been grading and comparing my basic bodice blocks. You should do this too because someone will eventually see the problem and it will be more difficult to fix.

I have drafted my basic bodice block three times, in each of my sample sizes for each of my size ranges - 12M, 3T, 5. (BTW, you can't use the same pattern piece and grade it in all the sizes. Believe me, that is one large headache). The next step is to grade each range separately. Keep in mind that each sample size will have slightly different shaping, but the general shape and proportion should be related.

Before getting too far, the outer fringes of each size range should be compared. For example, the size 18M should be smaller than the 24M/2T and the size 4T/4 should be smaller than the 5. Originally, I had graded the size 4T and 4 separately. In other words the 4T was based off the 3T sample and the 4 was based off the 5. The reason I combined the 4T and 4 was because the shape and overall size was so similar it was a duplication in effort, and I also ran into the problem where the 4T was actually larger than the 4. If you do separate out the sizes than the 4T must be smaller than the 4. If you don't check your grades, someone will bring two dresses to you and say the patterns are wrong, size labels are switched or some other problem.

In the photos below you can see the problem more clearly. In the top picture, the size 4 is laying on top of the 4T. You can see the 4 is smaller than the 4T. In the bottom picture the 4T is on top of the 4 and it is clearly longer with a larger armhole.

To solve this problem, I have been reworking my toddler patterns. I started by combining sizes 4T and 4 so I have one less size to grade. Next my toddler bodices were redrafted to have a shape similar to the 5 (less boxy, smaller armhole). Finally, I regraded the toddler patterns. This is still a work in progress, but the results are much better - each size is progressively larger.

I had the same problem with my size 18M and 24M/2T. In this case it wasn't a grading problem. Instead my infant patterns were proportionally too long compared to the toddler. I fixed this by shortening the bodice slightly.

Anyway, the point is that you should make sure and check the sizes on the outer fringes of each size range and make adjustments so that each size is progressively larger. You can adjust the grade rules (much easier in CAD, btw) or change the shape of the patterns.

(I am ignoring the idea that in the real world an 18M child could be larger than a 24M child. If that is the case, a parent would buy a larger size than 18M and just complain about the craziness of US sizing standards. When I did private label programs for the big box retailers their grade/POM charts progressively got larger with each size. Logically it makes sense even if reality is very different. Anyway, you can allow your sizes to overlap if you want, you'll just need to have an explanation as to why when a sewing contractor becomes confused.).

Anyway, I have tried to put the theory into practice and I have made some progress. I only offer my styles in sizes 3M to 6x. I am still working on the grades for the 4-6x styles, so I am nearly there. My sizes break down like this:

3M, 6M, 9M*, 12M, 18M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4

5, 6, 6x

I don't really consider the 9M as a true size. It is a half size between the 6M and 12M and is graded by splitting the grade between the 6M and 12M. The 24M and 2T are essentially the same as are the 4T and 4 - those sizes have been combined for grading purposes. My website still delineates the combined sizes as separate sizes.

This blog entry is not a discussion on the why and wherefores of children's sizing - a surprisingly complex and controversial topic. Instead, I wanted to show a possible grading/pattern problem that shows up now and then. I have been grading and comparing my basic bodice blocks. You should do this too because someone will eventually see the problem and it will be more difficult to fix.

I have drafted my basic bodice block three times, in each of my sample sizes for each of my size ranges - 12M, 3T, 5. (BTW, you can't use the same pattern piece and grade it in all the sizes. Believe me, that is one large headache). The next step is to grade each range separately. Keep in mind that each sample size will have slightly different shaping, but the general shape and proportion should be related.

Before getting too far, the outer fringes of each size range should be compared. For example, the size 18M should be smaller than the 24M/2T and the size 4T/4 should be smaller than the 5. Originally, I had graded the size 4T and 4 separately. In other words the 4T was based off the 3T sample and the 4 was based off the 5. The reason I combined the 4T and 4 was because the shape and overall size was so similar it was a duplication in effort, and I also ran into the problem where the 4T was actually larger than the 4. If you do separate out the sizes than the 4T must be smaller than the 4. If you don't check your grades, someone will bring two dresses to you and say the patterns are wrong, size labels are switched or some other problem.

In the photos below you can see the problem more clearly. In the top picture, the size 4 is laying on top of the 4T. You can see the 4 is smaller than the 4T. In the bottom picture the 4T is on top of the 4 and it is clearly longer with a larger armhole.

To solve this problem, I have been reworking my toddler patterns. I started by combining sizes 4T and 4 so I have one less size to grade. Next my toddler bodices were redrafted to have a shape similar to the 5 (less boxy, smaller armhole). Finally, I regraded the toddler patterns. This is still a work in progress, but the results are much better - each size is progressively larger.

I had the same problem with my size 18M and 24M/2T. In this case it wasn't a grading problem. Instead my infant patterns were proportionally too long compared to the toddler. I fixed this by shortening the bodice slightly.

Anyway, the point is that you should make sure and check the sizes on the outer fringes of each size range and make adjustments so that each size is progressively larger. You can adjust the grade rules (much easier in CAD, btw) or change the shape of the patterns.

(I am ignoring the idea that in the real world an 18M child could be larger than a 24M child. If that is the case, a parent would buy a larger size than 18M and just complain about the craziness of US sizing standards. When I did private label programs for the big box retailers their grade/POM charts progressively got larger with each size. Logically it makes sense even if reality is very different. Anyway, you can allow your sizes to overlap if you want, you'll just need to have an explanation as to why when a sewing contractor becomes confused.).

Labels:

Analysis,

Clothing for Children,

Comparison,

Grading,

Patternmaking,

Size Charts,

Sizing,

Tutorials

July 17, 2008

Product Review: Jacket and Pants set for a child pt. 1

Do you like these product reviews? Maybe I should call it product analysis? I like to look at how other people are making their products. Children's products, in particular, require a little bit different construction because they are so small.

Up next is part 1 of a 2 part series on a 2 piece set consisting of a yellow jacket and casual pants. It is picture intensive and I didn't want to post it all in one super long post. I won't tell you the size yet. Maybe you can guess in comments? The fabric is what I call a "popcorn" knit. I think the correct classification is pointelle, but I am not sure. Anyway, it is a textured knit and there are some surprising details that I wouldn't expect in a bulkier knit or in this size.

First up is the jacket. Raglan sleeves, pocket with welts, lined hood, separating zipper, and a screen printed image. I wonder how the screen printed image will hold up in the wash? It is probably tricky to get it to "stick" on a textured knit. All of the sleeve seams and hems have a decorative stitch from a coverstitch machine.

Here is a close-up of the pocket. I am not entirely sure how to do this in this knit fabric and have it come out so nice. There is no interfacing or reinforcement stitching that I can see. There is the top-stitching around it though.

BTW, the pocket is functional.

The inside of the jacket with the back of the pocket. You can see the pocket extends into the hem but comes just short of where the zipper is located. You can see the zipper is covered with a facing too.

The back neck has a facing in a striped knit fabric. Look at that nice curve on the bottom edge of the facing. Hard to do in a knit. BTW, the facing is not necessary. It is purely for hanger appeal. The neck is finished with a "bias" finish out of the striped knit. The hood is nicely lined too.

The sleeves are set in flat. The sleeves would have been hemmed first, set into the body and closed under the arm. This is typical in this size range and price point.

The seam end of the underarm is tacked down with a straight stitch machine. This is also typical. It prevents the seam from opening back up during wash and wear. You can backstitch with the overlock seam and eliminate this step, but tacking the seam down provides another benefit. It reduces a point of irritation.

Next time I will show the pants. If you have a guess on the size, submit it into comments. I think I left enough clues, so it shouldn't be too hard. I welcome any other questions or comments about the review....

Up next is part 1 of a 2 part series on a 2 piece set consisting of a yellow jacket and casual pants. It is picture intensive and I didn't want to post it all in one super long post. I won't tell you the size yet. Maybe you can guess in comments? The fabric is what I call a "popcorn" knit. I think the correct classification is pointelle, but I am not sure. Anyway, it is a textured knit and there are some surprising details that I wouldn't expect in a bulkier knit or in this size.

First up is the jacket. Raglan sleeves, pocket with welts, lined hood, separating zipper, and a screen printed image. I wonder how the screen printed image will hold up in the wash? It is probably tricky to get it to "stick" on a textured knit. All of the sleeve seams and hems have a decorative stitch from a coverstitch machine.

Here is a close-up of the pocket. I am not entirely sure how to do this in this knit fabric and have it come out so nice. There is no interfacing or reinforcement stitching that I can see. There is the top-stitching around it though.

BTW, the pocket is functional.

The inside of the jacket with the back of the pocket. You can see the pocket extends into the hem but comes just short of where the zipper is located. You can see the zipper is covered with a facing too.

The back neck has a facing in a striped knit fabric. Look at that nice curve on the bottom edge of the facing. Hard to do in a knit. BTW, the facing is not necessary. It is purely for hanger appeal. The neck is finished with a "bias" finish out of the striped knit. The hood is nicely lined too.

The sleeves are set in flat. The sleeves would have been hemmed first, set into the body and closed under the arm. This is typical in this size range and price point.

The seam end of the underarm is tacked down with a straight stitch machine. This is also typical. It prevents the seam from opening back up during wash and wear. You can backstitch with the overlock seam and eliminate this step, but tacking the seam down provides another benefit. It reduces a point of irritation.

Next time I will show the pants. If you have a guess on the size, submit it into comments. I think I left enough clues, so it shouldn't be too hard. I welcome any other questions or comments about the review....

July 10, 2008

Product Review: Corduroy Pants for a toddler

I haven't done a product review in a long time. This is an item randomly pulled from my stash, a pair of elastic waist corduroy pants in size 18 months.

There was a time when this heavy-weight corduroy was popular. Is it still popular for boys? Even though this is a heavy weight corduroy, I don't know that this would be very durable. 18 month old kids spend a lot of time on their knees and bums crawling and scooting around. Most are probably walking, but not all the time. Anyway, you can see it has a pieced front leg with a bias piece over the knee. The waist has tunneled elastic.

Here is a close-up of the knee. Stitching this fabric can pose challenges because it is a thick fabric. BTW, the fabric is cut nap up (smooth toward the waist). Doing this gives a richer, more luxurious look, but also turns the clothing into a giant lint trap.

Here is the inside view of the front leg. One thing you could do to add extra value is to line, possibly interface, the knee piece. It would add some extra durability. But maybe people don't care about that when the pants are $5.

This last picture shows the elastic. I imagine the pattern maker and sample sewer spent a lot of time figuring out the correct cut elastic measurement. The fabric weight and tunnel stitching can cause the elastic to stretch out and not recover properly unless you compensate. The elastic is attached to the waist with an overlock stitch, turned to the inside and topstitched. I don't think there is any other way to do an elastic waist in this fabric. Too bulky otherwise.

November 29, 2007

Aldrich vs. Armstrong pattern drafting books

The two most useful (IMO) books for children's pattern making are by Winifred Aldrich

From Tiki:

I've been doing the same, pouring over measuring charts and re-working patterns. My 4 y.o. is my fit model, though, so I do have the luxury (ha!) of dressing her up when I need a fit, but it's by no means easier than having a dress form that won't want to dance around the room while I'm trying to check the fit.If you draft your own versions from each method, I would be interested in hearing your comments. I agree with a lot of what Tiki has said about the ease of drafting Aldrich over Armstrong. Though I prefer Armstrong for some things. I am fairly certain that Aldrich created all of the drafts in her book. I think the points of reference are unique to each draft and can't be used for comparison between drafts. It may make things simpler if they were consistent. Also some of the differences may come down to European vs. American fit and expectations. Europeans tend to fit closer to the body - Americans have a boxier fit.

Thank you so much for your explanation below about the flat patterns. I meant to respond earlier, but then got caught up in the holiday madness. Anyway, after much pondering conceptually over the "right" pattern method, I was encouraged by your explanation, especially that it's the fit that matters, not so much the method for getting there. I know that probably sounds simple and obvious, but since I have no formal patternmaking training, everything is a learning experience and I sometimes get stymied because I want to do everything "right." So I finally put pencil to paper to draft Aldrich's and Armstrong's patterns and compare them to mine. My patterns are a more like Aldrich's classic, although my armhole shape isn't quite as cut out (so my armhole is somewhat in between her flat and classic). I think the shoulder width on her flat block is too wide, but I guess that's part of what creates a boxier fit versus the slimmer fit of her classic block.

I did notice that Aldrich seems to modify the front armhole and lowers the front shoulder slope even in her "flat" blocks for wovens (on the infant woven on p. 25 and on the body/shirt block on p. 39), although it's not as pronounced as in her classic block (on p. 89). And when I cut out my front and back patterns for the classic block and woven flat block, the shape and contrast between the front and back of each are not that different. In other words, the difference in the armhole shape between the front of the classic and the back of the classic is very similar to the difference in the armhole shape between the front woven flat block and the back woven flat block (I laid the fronts over the backs and compared). Of course, the armhole shaping between the front classic block and the front woven flat block are significantly different, as are the back classic and back woven flat. I'm not sure exactly what that means, really, except that she seems to apply the "true" flat (meaning identical front and back except for the neckline) as you suggested to casual knit boxy styles like t-shirts (which she drafts also for older children on p. 45).

One more thing about Aldrich's book that I find confusing. I do prefer her drafting method to Armstrong's (for children, I haven't done anything with either of their adult patterns)--it seems simpler because it uses fewer complicated measurements (I suppose because she makes certain educated assumptions about the slope of the shoulder, etc rather than using actual measurements).

However, her book seems a bit schizophrenic, like several people drafted different patterns and she compiled them into one book. For example, the points (0,1,2,3, etc) are not in the same places in her various patterns--sometimes point 0 is center front and sometimes it is a point just above center front that lines up with the inner shoulder. Then her patternmaking steps are not consistent throughout. Sometimes she measures the width from this point 0 and then squares down and sometimes she measures the width from the center chest and then squares from there. Her patterns all end up with the same basic shape and I found following her drafting instructions for each pattern very straightforward. But I think comparing one pattern to another is difficult because in one pattern point 3 is at center chest and on another pattern point 7 is at center chest and point 3 is somewhere else. Maybe it's just my inexperience, but I found it more difficult when trying to compare, say, the chest width ease from one pattern to another, than if she followed the same drafting steps for each bodice.

I do love both books as they are great at explaining how/where to modify patterns for different styles. And I like having two resources to compare--they are both a wealth of knowledge.

Anyway, here is a brief run down of the highlights (positive & negative) of each book:

Aldrich (third edition)

- Backs up measurement charts with her own measurement studies

- Simpler drafting, though some instructions may be difficult to follow

- Includes Infant sizing and basic infant drafts

- Draft instructions for flat and classic blocks

- The only book that comes close to how things are done in the industry

- The only nitpick I had was the shaping of some of her basic blocks. I agree with Tiki on the shoulder slope, shoulder width and the neckline circumference. These are easy things to adjust once you have a draft to work with. I also did not like her cap sleeve shaping - another thing that was easy to fix.

- Design variations are laid out on separate pages and not squished together like Aldrich.

- Step by step draft instructions

- Easy to read measurement chart, though her chart starts at size 3

- Chapter on knitwear

- Ignores infants

- Sleeve drafts have too much ease

October 18, 2007

Stewart Girl's Dress Patent of 1922

From the USPTO comes a patent filing for a girl's dress in 1922. The claim made by Gladys Matson Stewart is for the ornamental design of the dress, which I found rather difficult to see. Perhaps the ribbon belt? I guess the claim depends on the definition of ornamental design and I find her claim rather dubious. Perhaps if she filed the claim on the basis of how the dress is constructed, then perhaps her claim may be more legitimate. The design of the dress is structural and also very intriguing. I would like to sit down with designer and see how she constructed it. The gather details on the upper skirt sides would be especially difficult to sew in an industrial setting. I have tried in the past to come up with an easy way to do it, but haven't yet. The pattern itself is rather easy to create, its the construction that is the challenge.

The difficulty would be in getting the gathers to start right at the end of the slit and have them evenly distributed across the length of it. The next difficulty is overcasting or serging the seam so there are no raw edges while avoiding unsightly tucks. There is a physical/space limitation in inserting the skirt piece under a gather foot on a sewing machine. The detail would almost certainly require some kind of hand manipulation and would be too expensive for modern manufacturing.

The gather detail on the skirt would not be very attractive on an adult woman unless done in a certain way. It would add weight and attention to an area that most women choose not to emphasize. But a girl's dress could certainly get away with it. As a design idea, the detail could show up in lots of different ways and locations on a piece of clothing. The only road block is coming up with an easy mass construction technique.

The difficulty would be in getting the gathers to start right at the end of the slit and have them evenly distributed across the length of it. The next difficulty is overcasting or serging the seam so there are no raw edges while avoiding unsightly tucks. There is a physical/space limitation in inserting the skirt piece under a gather foot on a sewing machine. The detail would almost certainly require some kind of hand manipulation and would be too expensive for modern manufacturing.

The gather detail on the skirt would not be very attractive on an adult woman unless done in a certain way. It would add weight and attention to an area that most women choose not to emphasize. But a girl's dress could certainly get away with it. As a design idea, the detail could show up in lots of different ways and locations on a piece of clothing. The only road block is coming up with an easy mass construction technique.

Labels:

Analysis,

Design,

Dresses,

Intellectual Property,

Manufacturing,

Patents,

Sewing Techniques

July 26, 2007

Toddler Sweater Update

I started this sweater project over a year ago and it is still not finished. I finally blocked the pieces -- I doubt it was helpful when the sweater is made of synthetic yarn. One thing I noticed during the blocking process is how different the pieces looked from regular toddler patterns. There are several things I noticed that made me wonder...

The front piece has a t-shirt, boxy shape. The shoulder length looks too narrow and the front neck drop and width too big. I need to take measurements to see what toddler size this compares too.

The front piece has a t-shirt, boxy shape. The shoulder length looks too narrow and the front neck drop and width too big. I need to take measurements to see what toddler size this compares too. The back piece has no curve on the back neck. It is straight. I imagine a back neck curve is difficult to achieve in a knitted sweater. I wonder if this is typical in knitted garments? I don't knit enough sweaters to know. It could account for why the front neck is so big.

The back piece has no curve on the back neck. It is straight. I imagine a back neck curve is difficult to achieve in a knitted sweater. I wonder if this is typical in knitted garments? I don't knit enough sweaters to know. It could account for why the front neck is so big. The sleeve shaping seems fine, although they do bow out on the sides.

The sleeve shaping seems fine, although they do bow out on the sides.I have read books on knitwear design. One of these days I will draft my own basic knitwear design and try to knit up a sweater. In any event, all that's left on this sweater is to sew the pieces together and knit the neckband. I still haven't decided on the embellishment. Any ideas?

July 24, 2007

Boy's dress pants - an analysis

Here is a look at a pair of budget dress pants sized 24M. These were most likely sold by a big box retailer as part of a set that included a dress shirt and vest. They are 65% polyester, 35% rayon, made in Taiwan. Since these were likely sold as a set, it probably is not necessary for them to have all of the same details as an adult pair of pants. I call these pants budget because they would have sold for a low price point and were made from an inexpensive fabric. Still, there are some nice quality features.

The pants have 4 pleats in the front. 1" cuffs on pant legs. There are no pockets or other trimming details. (Click on the images for bigger close-ups). The front waist band is flat.

The pants have 4 pleats in the front. 1" cuffs on pant legs. There are no pockets or other trimming details. (Click on the images for bigger close-ups). The front waist band is flat. The back waistband has 1.25" stitch through elastic. Most infant/toddler pants or skirts have an elasticized back waist. This age group has a longer front waist than back waist. Combine this with a large seat (padded with a diaper) and it becomes necessary to take up the extra back width of the pant waist with elastic. The elastic is applied with a specialized machine that stretches the elastic while it is stitched on. Be sure to spec out the finished elastic measurement (the measurement of the elastic after it has been stitched). If you don't, the elastic will end up being too big or too small. A quality auditor (or you) should do in-line inspections during production. This is the one area that is the easiest to mess up.

The back waistband has 1.25" stitch through elastic. Most infant/toddler pants or skirts have an elasticized back waist. This age group has a longer front waist than back waist. Combine this with a large seat (padded with a diaper) and it becomes necessary to take up the extra back width of the pant waist with elastic. The elastic is applied with a specialized machine that stretches the elastic while it is stitched on. Be sure to spec out the finished elastic measurement (the measurement of the elastic after it has been stitched). If you don't, the elastic will end up being too big or too small. A quality auditor (or you) should do in-line inspections during production. This is the one area that is the easiest to mess up. You can see the nice neat finish of the waist side seam. The front waist band is stitched onto the front pant. The back waist has the elastic applied, turned to the inside and top stitched down. Some manufacturers will have a separate back waistband piece, but I like the nice smooth back waistband of this pant. The side seam is stitched by folding the front waistband to the front over the back elastic waist band. When the front band is turned out, the back waist is enclosed. Lower quality pants do not enclose this seam. Even though these pants are budget, the topstitching of the front waist band runs even with the lowest line of stitching for the elastic.

You can see the nice neat finish of the waist side seam. The front waist band is stitched onto the front pant. The back waist has the elastic applied, turned to the inside and top stitched down. Some manufacturers will have a separate back waistband piece, but I like the nice smooth back waistband of this pant. The side seam is stitched by folding the front waistband to the front over the back elastic waist band. When the front band is turned out, the back waist is enclosed. Lower quality pants do not enclose this seam. Even though these pants are budget, the topstitching of the front waist band runs even with the lowest line of stitching for the elastic. This is the only place where I could find the manufacturer truly skimped. The inside leg hem has a 1/2" hem which is topstitched down. This is a quicker finish than a blind hem and it can be hidden underneath the 1" cuff. To allow for future growth, you can add to the hem depth and do a blind hem instead. I wonder if there are many that would actually take the time to let the hem and cuff down, as simple as it is. Most parents would probably just buy another pair of pants.

This is the only place where I could find the manufacturer truly skimped. The inside leg hem has a 1/2" hem which is topstitched down. This is a quicker finish than a blind hem and it can be hidden underneath the 1" cuff. To allow for future growth, you can add to the hem depth and do a blind hem instead. I wonder if there are many that would actually take the time to let the hem and cuff down, as simple as it is. Most parents would probably just buy another pair of pants.

May 12, 2007

Neckline Finishes Examples

A friend asked me about the typical neckline finishes on childrenswear. There is a difference in the type of finish between adult and children's clothing. Adult clothing utilizes either linings, facings, and occasionally a bias binding finish. Children's clothing eliminates most facings, unless they are top-stitched down. Facings get in the way of dressing a child and roll out frequently. Another option is to have a full, flat lining usually seen on special occasion dresses. The majority of neckline finishes on children's clothing consists of bias binding.

There are several advantages to using bias binding. It is inexpensive and relatively easy to apply - you eliminate extra pattern pieces and reduce fabric usage. A bias facing is relatively flat and smooth, which may increase comfort. A bias facing can be made of self-fabric or contrasting. It can become a design element.

Here are just a few examples:

This is a typical example. This button-front, velveteen dress has a bias facing made of the same fabric as the collar. Usually the facing is made of the same fabric as the collar, rather than the body of the garment. This is so the facing appears to blend with the collar and not show from the front. If there were no collar, the neckline would still be finished with a bias facing, but the color would match the dress instead.

This is a typical example. This button-front, velveteen dress has a bias facing made of the same fabric as the collar. Usually the facing is made of the same fabric as the collar, rather than the body of the garment. This is so the facing appears to blend with the collar and not show from the front. If there were no collar, the neckline would still be finished with a bias facing, but the color would match the dress instead.

This is a sweatshirt style jacket. The bias facing is made of a cotton broadcloth that matches the decorative stitching. This is a good example of how the facing can be a design element. It also disguises an otherwise unsightly seam.

This is a sweatshirt style jacket. The bias facing is made of a cotton broadcloth that matches the decorative stitching. This is a good example of how the facing can be a design element. It also disguises an otherwise unsightly seam.

A bias facing used on a knit style top that has a back zipper opening. The end of the bias is turned under near the top of the zipper. No need for a special facing pattern to deal with the zipper.

A bias facing used on a knit style top that has a back zipper opening. The end of the bias is turned under near the top of the zipper. No need for a special facing pattern to deal with the zipper.

This is an example of a poorly executed use of a regular facing. The facing is much too narrow and floats up. The seam is bulky because of the ruffle sandwiched between the facing and the neck. This is a size 3-6M top and the facing and bulky neckline seam could be an irritant. The neckline seam should be serged together to reduce bulk and the facing should be top-stitched down. A bias facing would probably work better.

This is an example of a poorly executed use of a regular facing. The facing is much too narrow and floats up. The seam is bulky because of the ruffle sandwiched between the facing and the neck. This is a size 3-6M top and the facing and bulky neckline seam could be an irritant. The neckline seam should be serged together to reduce bulk and the facing should be top-stitched down. A bias facing would probably work better.

There are several advantages to using bias binding. It is inexpensive and relatively easy to apply - you eliminate extra pattern pieces and reduce fabric usage. A bias facing is relatively flat and smooth, which may increase comfort. A bias facing can be made of self-fabric or contrasting. It can become a design element.

Here are just a few examples:

This is a typical example. This button-front, velveteen dress has a bias facing made of the same fabric as the collar. Usually the facing is made of the same fabric as the collar, rather than the body of the garment. This is so the facing appears to blend with the collar and not show from the front. If there were no collar, the neckline would still be finished with a bias facing, but the color would match the dress instead.

This is a typical example. This button-front, velveteen dress has a bias facing made of the same fabric as the collar. Usually the facing is made of the same fabric as the collar, rather than the body of the garment. This is so the facing appears to blend with the collar and not show from the front. If there were no collar, the neckline would still be finished with a bias facing, but the color would match the dress instead. This is a sweatshirt style jacket. The bias facing is made of a cotton broadcloth that matches the decorative stitching. This is a good example of how the facing can be a design element. It also disguises an otherwise unsightly seam.

This is a sweatshirt style jacket. The bias facing is made of a cotton broadcloth that matches the decorative stitching. This is a good example of how the facing can be a design element. It also disguises an otherwise unsightly seam. A bias facing used on a knit style top that has a back zipper opening. The end of the bias is turned under near the top of the zipper. No need for a special facing pattern to deal with the zipper.

A bias facing used on a knit style top that has a back zipper opening. The end of the bias is turned under near the top of the zipper. No need for a special facing pattern to deal with the zipper. This is an example of a poorly executed use of a regular facing. The facing is much too narrow and floats up. The seam is bulky because of the ruffle sandwiched between the facing and the neck. This is a size 3-6M top and the facing and bulky neckline seam could be an irritant. The neckline seam should be serged together to reduce bulk and the facing should be top-stitched down. A bias facing would probably work better.

This is an example of a poorly executed use of a regular facing. The facing is much too narrow and floats up. The seam is bulky because of the ruffle sandwiched between the facing and the neck. This is a size 3-6M top and the facing and bulky neckline seam could be an irritant. The neckline seam should be serged together to reduce bulk and the facing should be top-stitched down. A bias facing would probably work better.

Labels:

Analysis,

Clothing for Children,

Finishes,

Samples,

Sewing Techniques,

Trims,

Tutorials

April 10, 2007

Country of Origin labeling examples

One comment from a reader on my Designers hate care/content labeling blog made a good point. Labels can be very irritating to the end user. Rest assured, it is perfectly legal to remove labels after purchase. The size and placement of labels should concern designers because it is all related to your brand. I searched through my stash to find examples of how other designers deal with US labeling requirements. I could not find any pieces that did not comply with labeling requirements. I guess I tend to buy product that is honest in their labeling. Clothing that leave off labels or fail to place them properly says something about your company (and it isn't good IMO). All of these examples have the labels correctly placed near the back neck with the country of origin prominently displayed.

Country of origin as part of the brand label. This is also one of my rare Made in USA pieces.

Country of origin as part of the brand label. This is also one of my rare Made in USA pieces.

A size tag/country of origin label stitched to the bottom of the brand label.

A size tag/country of origin label stitched to the bottom of the brand label.

A separate size/country of origin label placed next to the brand label.

A separate size/country of origin label placed next to the brand label.

This is a typical example. The brand label is stacked on top of the care/content tag. The country of origin clearly shows below the brand tag.

Country of origin as part of the brand label. This is also one of my rare Made in USA pieces.

Country of origin as part of the brand label. This is also one of my rare Made in USA pieces. A size tag/country of origin label stitched to the bottom of the brand label.

A size tag/country of origin label stitched to the bottom of the brand label. A separate size/country of origin label placed next to the brand label.

A separate size/country of origin label placed next to the brand label.

This is a typical example. The brand label is stacked on top of the care/content tag. The country of origin clearly shows below the brand tag.

Labels:

Analysis,

Care/Content Tags,

FTC,

Labels,

Regulations,

Technical Design

April 03, 2007

Designers hate care/content labels

I was shopping a week ago or so in one of my favorite discount stores, Ross Dress for Less. As I was working my way through the blouse rack, I noticed a significant problem with most of the blouses on the rack. The blouses did not have a proper notification of country of origin (I would of counted how many were not in compliance, but DH was getting bored). According to FTC recommendations, items with a neckline must have a label stating the country of origin at or near the inside center back neck. These blouses only had a small brand label. A separate care label was attached to a side seam, with country of origin disclosed there.

I have read the FTC recommendations dozens of times and I am always surprised of the amount of non-compliance that exists in the marketplace. Some companies must be ignoring (or are ignorant) of the requirement. Further, many of the items in this store are imports. This means they had to pass custom inspections. I don't get it.

I follow the rules, and yet I have seen many designers insist they don't have to place a label at the back neck. After all, it is ugly and takes away from hanger appeal. If no one else is doing it, why should they. Children's clothing poses an additional challenge - there is only so much space in the back neck.

Here is a picture of an infant girl's dress. The label is correctly placed near the back neck. This placement requirement creates consistency across a broad range of products. Customers can know where to find basic product information. If I wanted to purchase Made in USA product, then it would be simple to find out.

Here is a picture of an infant girl's dress. The label is correctly placed near the back neck. This placement requirement creates consistency across a broad range of products. Customers can know where to find basic product information. If I wanted to purchase Made in USA product, then it would be simple to find out.

It is only required that country of origin information be placed in a reasonable, accessible place (generally the back neck in items with a neck). Care information may be placed in a side seam, or elsewhere. Generally, children's items have the information combined on one tag. Think about your customers. Do you really want them to have to fish through an entire item of clothing to see where it was made and how it should be cleaned?

I have read the FTC recommendations dozens of times and I am always surprised of the amount of non-compliance that exists in the marketplace. Some companies must be ignoring (or are ignorant) of the requirement. Further, many of the items in this store are imports. This means they had to pass custom inspections. I don't get it.

I follow the rules, and yet I have seen many designers insist they don't have to place a label at the back neck. After all, it is ugly and takes away from hanger appeal. If no one else is doing it, why should they. Children's clothing poses an additional challenge - there is only so much space in the back neck.

Here is a picture of an infant girl's dress. The label is correctly placed near the back neck. This placement requirement creates consistency across a broad range of products. Customers can know where to find basic product information. If I wanted to purchase Made in USA product, then it would be simple to find out.

Here is a picture of an infant girl's dress. The label is correctly placed near the back neck. This placement requirement creates consistency across a broad range of products. Customers can know where to find basic product information. If I wanted to purchase Made in USA product, then it would be simple to find out.It is only required that country of origin information be placed in a reasonable, accessible place (generally the back neck in items with a neck). Care information may be placed in a side seam, or elsewhere. Generally, children's items have the information combined on one tag. Think about your customers. Do you really want them to have to fish through an entire item of clothing to see where it was made and how it should be cleaned?

February 22, 2007

A CEO's experience is important - the Difficulty at The Gap in 2007

I love BabyGap. I think the designers do an incredible job. The product looks fresh and cute, and it is priced reasonably. I read a very interesting article in February's 26th Business Week, Paul Pressler's Fall From The Gap. My first reaction was here is someone who didn't read Kathleen's book . Reading through the article (and if you can believe everything in it), one can see he clearly didn't understand the fashion business. It would be easy to put all of the blame on him because he was the new guy. The truth is that GAP has corporate culture issues not unlike any large company.

. Reading through the article (and if you can believe everything in it), one can see he clearly didn't understand the fashion business. It would be easy to put all of the blame on him because he was the new guy. The truth is that GAP has corporate culture issues not unlike any large company.

I met an assistant designer for GAP years ago. The impression she left was not very favorable. At least I decided I would not work there, if given the choice. It was a pretty cut throat environment with people climbing the corporate ladder rather quickly because of constant turn over. She left the impression that she could be become one of the head designers within a few years. Success like that does not happen without a lot of back-stabbing.

So I don't blame him entirely for his failure to turn things around at GAP. It would not have been an easy task to walk into a difficult corporate culture, with little fashion experience. Some of his decisions illustrated in the article were indeed poor, others just missed the mark. I think design entrepeneurs can learn from him. Here are my thoughts on some of his decisions:

1. Combining fabric purchases. He made the mistake of combining denim sales for all four divisions of GAP, including Old Navy, Banana Republic, and Forthe and Towne. The result was that all divisions ended up with exactly the same denim to use in all of their denim styles. There is no point in having four divisions if there is not some kind of difference in the clothing. Why buy denim jeans at Banana Republic when you can get the same thing at Old Navy for less money?

The idea is not without merit. I have had corporate execs suggest the same in the past. The goal is to negotiate a lower price for the raw materials by buying in bulk. A small company can combine fabric purchases to also negotiate a lower price. The point is that you shouldn't buy only one fabric, or one style of fabric. Large fabric mills will push you in that direction because it is less expensive for them to run 10,000 yards of the same denim fabric. But what are you going to do with 10,000 yards of denim?

A small business is more likely going to need, say, 300 yards of denim, which will cost more than what GAP will pay. But you can still negotiate a lower price. Sometimes, your order can be combined with an order from another company. Both companies could benefit with a lower price. Perhaps, you could up your order to 500 yards and you can use the extra fabric the next season or in another style. If the fabric company has more than one type of fabric, perhaps you could combine your fabric needs with one company. A long term relationship between supplier and buyer can lead to lower prices.

A small business should never buy ALL of their fabric from one source. You never know what could happen, so make sure to have back-up choices.

2. Outsourcing development. Pressler required his designers to create their patterns in the states and then have the samples made in Asia. Sample making in Asia is cheaper. The problem is time. It takes time to mail samples and patterns back and forth. Even with internet technology, there are many barriers to the ease of communication. Language differences is the biggest. This kind of product development can take as long as 3-4 months for final product approval, especially on a new style. Pressler would not give approval for expedited shipping.

You can outsource product development. It should be something to consider, especially for childrenswear designers. A lot of children's clothing is made overseas - just shop the competition and you will see very few USA labels. Because competition is so stiff, you can save a lot in labor by moving overseas.

If you decide to take this road, give yourself plenty of time. Time to find a reputable manufacturer. Time to find a manufacturer that will run smaller lots (small is a relative term, but expect 500-1000 pc runs to be termed "small"). Time to teach the manufacturer and their technical people your product and quality standards. You can do a lot of things long distance. One Chinese manufacturer preferred that designers actually come and spend a few weeks in China working directly with a patternmaker to develop samples. Not only was it faster, but it ensured the designer got what they wanted.

3. Market Research. Pressler tried to use traditional market research tactics to predict the next big trend. The problem is that customers look to their favorite brands to lead on the next trend. This means that designers predict or envision what should happen next. Fashion companies rely on their designers for this.

Market research is important for building a better brand and better product. Designers do need to listen to their customers. I have seen a few online fashion companies add product reviews and customer comments on their sites. This type of system can help a company improve problems faster. Inspect returns for product defects. Learning from the past can help you move forward.

What will happen at the GAP next? They are now on the hunt for a CEO with apparel experience. I don't see the death of GAP, but I do see some serious growing problems.

I met an assistant designer for GAP years ago. The impression she left was not very favorable. At least I decided I would not work there, if given the choice. It was a pretty cut throat environment with people climbing the corporate ladder rather quickly because of constant turn over. She left the impression that she could be become one of the head designers within a few years. Success like that does not happen without a lot of back-stabbing.

So I don't blame him entirely for his failure to turn things around at GAP. It would not have been an easy task to walk into a difficult corporate culture, with little fashion experience. Some of his decisions illustrated in the article were indeed poor, others just missed the mark. I think design entrepeneurs can learn from him. Here are my thoughts on some of his decisions:

1. Combining fabric purchases. He made the mistake of combining denim sales for all four divisions of GAP, including Old Navy, Banana Republic, and Forthe and Towne. The result was that all divisions ended up with exactly the same denim to use in all of their denim styles. There is no point in having four divisions if there is not some kind of difference in the clothing. Why buy denim jeans at Banana Republic when you can get the same thing at Old Navy for less money?

The idea is not without merit. I have had corporate execs suggest the same in the past. The goal is to negotiate a lower price for the raw materials by buying in bulk. A small company can combine fabric purchases to also negotiate a lower price. The point is that you shouldn't buy only one fabric, or one style of fabric. Large fabric mills will push you in that direction because it is less expensive for them to run 10,000 yards of the same denim fabric. But what are you going to do with 10,000 yards of denim?

A small business is more likely going to need, say, 300 yards of denim, which will cost more than what GAP will pay. But you can still negotiate a lower price. Sometimes, your order can be combined with an order from another company. Both companies could benefit with a lower price. Perhaps, you could up your order to 500 yards and you can use the extra fabric the next season or in another style. If the fabric company has more than one type of fabric, perhaps you could combine your fabric needs with one company. A long term relationship between supplier and buyer can lead to lower prices.

A small business should never buy ALL of their fabric from one source. You never know what could happen, so make sure to have back-up choices.

2. Outsourcing development. Pressler required his designers to create their patterns in the states and then have the samples made in Asia. Sample making in Asia is cheaper. The problem is time. It takes time to mail samples and patterns back and forth. Even with internet technology, there are many barriers to the ease of communication. Language differences is the biggest. This kind of product development can take as long as 3-4 months for final product approval, especially on a new style. Pressler would not give approval for expedited shipping.

You can outsource product development. It should be something to consider, especially for childrenswear designers. A lot of children's clothing is made overseas - just shop the competition and you will see very few USA labels. Because competition is so stiff, you can save a lot in labor by moving overseas.

If you decide to take this road, give yourself plenty of time. Time to find a reputable manufacturer. Time to find a manufacturer that will run smaller lots (small is a relative term, but expect 500-1000 pc runs to be termed "small"). Time to teach the manufacturer and their technical people your product and quality standards. You can do a lot of things long distance. One Chinese manufacturer preferred that designers actually come and spend a few weeks in China working directly with a patternmaker to develop samples. Not only was it faster, but it ensured the designer got what they wanted.

3. Market Research. Pressler tried to use traditional market research tactics to predict the next big trend. The problem is that customers look to their favorite brands to lead on the next trend. This means that designers predict or envision what should happen next. Fashion companies rely on their designers for this.

Market research is important for building a better brand and better product. Designers do need to listen to their customers. I have seen a few online fashion companies add product reviews and customer comments on their sites. This type of system can help a company improve problems faster. Inspect returns for product defects. Learning from the past can help you move forward.

What will happen at the GAP next? They are now on the hunt for a CEO with apparel experience. I don't see the death of GAP, but I do see some serious growing problems.

February 13, 2007

Another Care/Content Label Example

It's time to look at another care/content label. These labels were found in a 12M knit top that is part of a two-piece set.

It's time to look at another care/content label. These labels were found in a 12M knit top that is part of a two-piece set.The first thing that caught my eye was the placement of the country of origin. Country of origin information must be placed so that it can be seen without flipping the label over. Nothing can cover the country of origin information, like a brand label. It should be placed in an easily accessible area, like the back neck or waistband.

Another interesting observation is the style number and lot number information included on the front of the label. The lot number probably refers to the production lot and corresponds to a date of manufacture (lot numbers are unique to each company, so it could mean almost anything). Generally, this information is found elsewhere, like the reverse of the tag or even on a separate tag stuck into a side seam. It is certainly not anything that a customer is going to care about. I like the inclusion of this info for easy back-tracking, but it should be placed elsewhere.

This tag contains both an RN and CA numbers. The CA number is the Canadian equivalent to the the US RN number. This product was most likely sold in both Canada and the US, thus the need for two numbers.

The reverse side of the label contains all relevant information. My only nit-pick is the overall formatting. I generally prefer the content information first, followed by the care info. This label is just the opposite. Further, the content information is a different font, font size, and right-aligned compared to the care instructions. It makes the whole reverse side appear sloppy.

My final nit-pick is that the label should say "2 piece set" somewhere. Inevitably, the two pieces will be separated. This helps the shipping and store employees on the retail end realize there should be two pieces on the hanger.

Labels:

Analysis,

Care/Content Tags,

FTC,

Labels,

Regulations,

Technical Design,

Tracking

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)