I picked up this t-shirt on clearance at Wal-mart. The embroidery caught my attention and at only $5 it was worth taking a chance. The style is meant to be loose, so the t-shirt itself is boxy. There is a drawstring casing at the high hip level to cinch it in. I did get compliments when wearing this, but it was not comfortable. The fit was just too sloppy for my tastes.

So I pulled out my TNT t-shirt pattern that I made a few years ago. My initial thought was to just cut down the shirt to match the fit of my pattern. Essentially using the t-shirt as a fabric rather than a shirt.

There are a few problems that stopped me. First is the casing. I debated on cutting out the casing and just having a band on the bottom hem but I was concerned the seam would be in a weird place. The next problem was the sleeve. There really isn't enough fabric to recut the sleeve.

Looking now at the picture, I wonder if I should take in the sides and call it good? What do you think?

Showing posts with label Fitting. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Fitting. Show all posts

March 10, 2015

June 16, 2014

Sleeve cap ease to fit around your shoulder is a myth

My most popular blog entry is Tutorial: Reduce/Remove Sleeve Cap Ease. Excessive ease in set-in sleeves continues to be a source of frustration for many. Still, there are those that continue to insist that sleeve cap ease is necessary in order for a sleeve to fit over the curve of your shoulder. Another well meaning sewist claimed my tutorial only worked for children's clothing (my specialty) because children are smaller, but adults definitely need ease.

Kathleen has written a now classic blog entry, Sleeve Cap Ease is Bogus (including a sequel). She even did a series on how to draft an armhole and sleeve correctly so that no ease is needed (partially gated). It would be worth your time to go back and reread those blog entries.

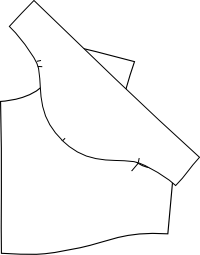

This idea that ease is needed for proper fit is interesting. Unfortunately, it is a false concept. A sleeve should not fit over the curve of a shoulder. Instead, the sleeve should hang straight down from the shoulder. The shoulder seam needs to extend long enough that it reaches to the widest part or tip of the shoulder. In the picture below you can see the shape of both the shoulder and armhole. This draft will allow the sleeve to hang from the shoulder.

Kathleen goes into greater detail about this in her blog entries. If you draft a sleeve as instructed by many pattern making manuals with the recommended 1-2 inches of ease, you will not be able to get beautiful looking sleeves like the ones found being worn by the actors of His Girl Friday. Notice the placement of the armhole seams.

Instead, you will get a sleeve that looks something like this:

|

| Photo courtesy of Kelly Hogaboom and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. |

Sleeve caps with ease amount to lazy pattern making, or at the very least pattern making without knowing better.

Children are really not much different when it comes to fit and pattern design. They do have fewer overall curves, so in many ways pattern making and fit are simpler. What curves they do have though, are smaller. Sewing a set-in sleeve in an infant sized bodice is in many ways more difficult. There is less length to work with and tighter curves. If ease is included it is just enough to allow the operator to get around that smaller circumference easier. The amount of ease is very small (1/4 to 1/2 inch) and is entirely dependent on the fabric. In many cases, it is not needed at all because the differential of a machine can be adjusted.

I can understand if this seems unbelievable. It certainly goes against the grain of conventional sewist wisdom. The best way to know, is to try it for yourself. Try using a pattern with sleeve cap ease and one without. Which sleeve is easier to sew in? Which looks better? At the end of the day, you choose which sleeve you prefer to work with.

January 23, 2014

Shoulder slope pattern correction

LisaB asked me to explain:

Not everyone will need to make this adjustment. This was a problem inherent in my own patterns to fit me. The drawing below, I hope more clearly shows how the shoulder seam was laying.

Raise the shoulder at the neckpoint 3/8" on front bodice to correct shoulder slope problem. I need to apply this correction to my t-shirt pattern too.I tried my first cardigan sample on several times and noticed the shoulder seam was not pointing in the right direction. The seam at the neck point was pointing toward the front rather than laying right on top of my shoulder. I also looked at my t-shirt pattern and observed the same problem. This indicates a possible shoulder slope problem or shoulder to hem length problem on either the front or the back bodice or both. To figure this out, I ran a basting thread in my cardigan shoulder seam area and looked in the mirror to see where I needed to make the adjustment (no fitting buddy or dressform at my house, unfortunately). I also pulled out my blouse pattern and compared the shoulder seam. In the end, I needed to move the shoulder up at the neckpoint 3/8" on the front bodice. This increased the shoulder to hem length on the front just enough to allow the back bodice to relax backward and position the shoulder seam right on top of the shoulder.

Not everyone will need to make this adjustment. This was a problem inherent in my own patterns to fit me. The drawing below, I hope more clearly shows how the shoulder seam was laying.

December 11, 2013

Adapting a block pattern into something else pt. 7 : Pattern modifications

Have you ever had a project bug you? I had my first sample hanging in the Design Loft almost taunting me. Originally I wanted a neckband on my cardigan. Then during construction, I changed to a rolled fabric edge along the neckline. The longer I stared at it, the less I liked it. Still unsure how a folded neckband would look, I whipped up a small sample, and what do you know? It worked just fine. It could be improved with a bit of interfacing, but not too bad.

So I pulled out the seam ripper and set to work. In addition, I removed some of the extra ease I had previously added for a closer fit.

You'll notice there are still a few minor adjustments that need to be made. The sleeves are too long. Yep, I over compensated there. The shoulder needs to be brought back up. And the back neckline needs to be raised. Despite all that, I am fairly pleased with the results. This is the style of cardigan that I really like. It looks sloppy in the photo because I used a rayon/poly jersey knit that is just too lightweight and drapey for the style. The next version will be even better. And yes I do plan to wear this, even in public. It is very, very comfortable.

November 21, 2013

Adapting a block pattern into something else pt. 6 : Sewing a fitting sample

You can easily spend a lot of time creating a pattern on paper but at some point, it needs to be sewn up. It is while sewing that you'll see your design take shape and lead you to make modifications as needed. I changed the design a bit by eliminating the folded neckband. The neckband is instead a single layer that is allowed to roll. I made this change because the fabric is pretty light and it would need some kind of stabilizer, which I didn't have. The cardigan is very comfortable and fits pretty well. Even so, I added just a bit too much wearing ease. So I need to reduce some of the body width. The upper back is a tad long and the sleeves need shortened.

It's pretty hard to get everything just right on the first attempt. I've done enough girls dress patterns that I don't usually have to do many iterations. Adult clothing takes a bit more tries because I lack experience with it. Industry pattern makers and sample makers will sometimes make many iterations of a design before they get it just right. This is a slightly different approach than home sewists might take. But once the pattern is nailed down, I won't have to worry about it anymore. It will be much easier to create variations on this style too.

Before I could tackle the pattern adjustments, I needed to stop and get organized. I assigned a style number, created a style and cutting spec sheet, and assigned pattern numbers. I explain how to do this along with providing printable blank forms to fill out in my book. If you prefer keeping a digital record, you can use the examples in the book to create your own spreadsheets. In many ways I still prefer paper and pencil. It forces your brain to think differently - perhaps more analytically. I have used both paper and pencil and spreadsheets. There are advantages to both.

It's pretty hard to get everything just right on the first attempt. I've done enough girls dress patterns that I don't usually have to do many iterations. Adult clothing takes a bit more tries because I lack experience with it. Industry pattern makers and sample makers will sometimes make many iterations of a design before they get it just right. This is a slightly different approach than home sewists might take. But once the pattern is nailed down, I won't have to worry about it anymore. It will be much easier to create variations on this style too.

Before I could tackle the pattern adjustments, I needed to stop and get organized. I assigned a style number, created a style and cutting spec sheet, and assigned pattern numbers. I explain how to do this along with providing printable blank forms to fill out in my book. If you prefer keeping a digital record, you can use the examples in the book to create your own spreadsheets. In many ways I still prefer paper and pencil. It forces your brain to think differently - perhaps more analytically. I have used both paper and pencil and spreadsheets. There are advantages to both.

April 11, 2012

T-shirt pattern quest pt. 6 : How to correct the fit of the armhole of a fitted t-shirt

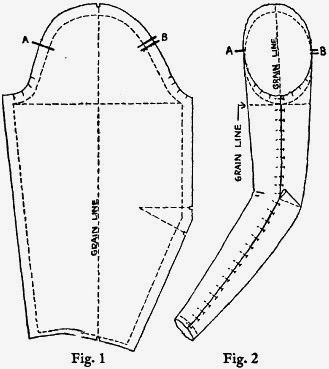

I created some drawings to further explain the armhole problem on my t-shirt pattern. Nearly all drafting instructions that I've seen for t-shirts are pretty much the same. First you enlarge the armhole and drop the shoulder. Then the front and back bodice are traced off with identical bodice shaping and armhole shaping. The only difference might be the neck. If you lay the pattern pieces on top of each other, you will get something like this.

This kind of pattern works ok for a boxy, loose fitting t-shirt. If you want a more fitted t-shirt, then it simply won't work. In my case, the symmetrical armholes caused the front of the shirt to be pulled toward the back. The closer the fit, the less symmetry in general. When you look at the human body, you can see there is no symmetry between the front and back so patterns should reflect this. (Most people are not truly symmetrical left to right either). Children generally are more symmetrical than adults and the patterns for them reflect this. But, even there, the more fitted the style, the less symmetry though the differences are smaller. Anyway, the patterns above resulted in a fit that looked like below. The red arrows help emphasize the shape and length differences of the front and back armholes.

To correct this problem, I needed to lengthen the back armhole. I compared the armhole of my blouse pattern, which was not symmetrical, to the t-shirt armhole to determine how much longer it should be. Slash and spread and the pattern should look like something below.

With a result that looks much improved.

The next thing on my list is to make adjustments for front versus back body width.

This kind of pattern works ok for a boxy, loose fitting t-shirt. If you want a more fitted t-shirt, then it simply won't work. In my case, the symmetrical armholes caused the front of the shirt to be pulled toward the back. The closer the fit, the less symmetry in general. When you look at the human body, you can see there is no symmetry between the front and back so patterns should reflect this. (Most people are not truly symmetrical left to right either). Children generally are more symmetrical than adults and the patterns for them reflect this. But, even there, the more fitted the style, the less symmetry though the differences are smaller. Anyway, the patterns above resulted in a fit that looked like below. The red arrows help emphasize the shape and length differences of the front and back armholes.

To correct this problem, I needed to lengthen the back armhole. I compared the armhole of my blouse pattern, which was not symmetrical, to the t-shirt armhole to determine how much longer it should be. Slash and spread and the pattern should look like something below.

With a result that looks much improved.

The next thing on my list is to make adjustments for front versus back body width.

March 06, 2008

Tutorial: Reduce/Remove Sleeve Cap Ease

I have written an additional entry on sleeve cap ease. After reading this entry be sure to check out Reduce/Remove sleeve cap ease pt. 2.

Melissa wrote some comments on my blog entry A Problem with Cap Sleeves:

Just a few more words before you get to the drawings. This is just my method - Armstrong's is similar. My hope is to just illustrate the principle and not hard fast rules. You can have ease, if you choose, thus the tutorial is on how to reduce or remove the ease. You can use this same method to fix the patterns from the Big 4 - which notoriously have too much sleeve cap ease.

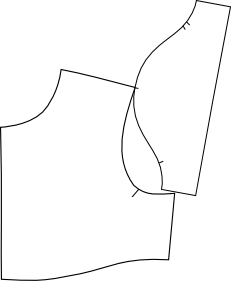

Before you can remove/reduce sleeve cap ease, you need to know how much ease the sleeve already has. To do this you need to "walk" the sleeve cap along the armscye - without seam allowances. This is one of the few times I actually remove seam allowances when pattern making because they actually might get in the way. Align the center sleeve notch with the shoulder seam and walk the pattern along until you get to the underarm seam. Armstrong does this procedure just the opposite by starting at the underarm seam and moving toward the shoulder. Either way will work and her method is probably better. I usually do this in a CAD environment and my brain says start at the shoulder. It doesn't really matter so do what you think is right.

Before you can remove/reduce sleeve cap ease, you need to know how much ease the sleeve already has. To do this you need to "walk" the sleeve cap along the armscye - without seam allowances. This is one of the few times I actually remove seam allowances when pattern making because they actually might get in the way. Align the center sleeve notch with the shoulder seam and walk the pattern along until you get to the underarm seam. Armstrong does this procedure just the opposite by starting at the underarm seam and moving toward the shoulder. Either way will work and her method is probably better. I usually do this in a CAD environment and my brain says start at the shoulder. It doesn't really matter so do what you think is right.

More walking.

More walking.

Still walking. You can see at this point that my underarm notches meet up. This won't be true in the real world - this is just how my drawing ended up. When I am done altering the sleeve, I move the notches where I need them to be. Right now my goal is to get the sleeve cap and armscye to be the same distance. This is where the Armstrong method might work better for you as the underarm notches don't move.

Still walking. You can see at this point that my underarm notches meet up. This won't be true in the real world - this is just how my drawing ended up. When I am done altering the sleeve, I move the notches where I need them to be. Right now my goal is to get the sleeve cap and armscye to be the same distance. This is where the Armstrong method might work better for you as the underarm notches don't move.

Finally done walking. Now measure any of the sleeve cap that is left over. This is how much ease you have on the front. Yes, sleeves have a front and a back and I only walked my sleeve along the front armscye. You will need to repeat the procedure since most of you will have assymetric sleeves. My sleeves tend to be symmetric for children so I only have to walk the pattern on one side. Make sense? Now that you know how much ease you have, you can decide how much to remove.

Finally done walking. Now measure any of the sleeve cap that is left over. This is how much ease you have on the front. Yes, sleeves have a front and a back and I only walked my sleeve along the front armscye. You will need to repeat the procedure since most of you will have assymetric sleeves. My sleeves tend to be symmetric for children so I only have to walk the pattern on one side. Make sense? Now that you know how much ease you have, you can decide how much to remove.

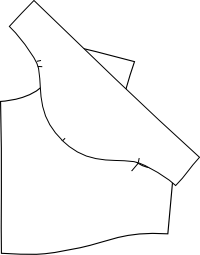

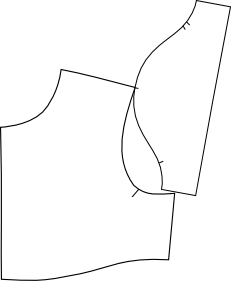

This is where things can get a little fiddly... There are a few different ways to remove sleeve cap ease. I usually use a combination of these methods because I want to maintain a nice sleeve cap shape. Not too flat and not too round. My eyes have been trained to recognize a good sleeve cap shaping and it is not something I can pass along to you. You will have to experiment a little bit to see what works best. Try to keep the convex and concave curves balanced (again, how to explain that?). In this drawing I show two places to reduce ease. The first is to shorten the bicep line by moving in the underarm seam. Armstrong's extra 2 inches is too much for children. It may be too much for adults too. It all depends on your desired fit. The next place to remove ease is to lower the sleeve cap height. With my cap sleeve, I lowered the sleeve cap height at least 1/2 inch and re-drew the cap. Again it depends on your fit and the shape of your sleeve to begin with.

This is where things can get a little fiddly... There are a few different ways to remove sleeve cap ease. I usually use a combination of these methods because I want to maintain a nice sleeve cap shape. Not too flat and not too round. My eyes have been trained to recognize a good sleeve cap shaping and it is not something I can pass along to you. You will have to experiment a little bit to see what works best. Try to keep the convex and concave curves balanced (again, how to explain that?). In this drawing I show two places to reduce ease. The first is to shorten the bicep line by moving in the underarm seam. Armstrong's extra 2 inches is too much for children. It may be too much for adults too. It all depends on your desired fit. The next place to remove ease is to lower the sleeve cap height. With my cap sleeve, I lowered the sleeve cap height at least 1/2 inch and re-drew the cap. Again it depends on your fit and the shape of your sleeve to begin with.

Another way to reduce sleeve cap ease is to split the pattern and overlap it - similar to these drawings (remember I am only working on the front side so don't forget to do the back). Redraw the sleeve cap. This method reduces the bicep but may help preserve the cap shaping.

Another way to reduce sleeve cap ease is to split the pattern and overlap it - similar to these drawings (remember I am only working on the front side so don't forget to do the back). Redraw the sleeve cap. This method reduces the bicep but may help preserve the cap shaping.

As I stated before, I probably did a combination of these three methods so that I didn't do anything too drastic. It will take subtle changes to distribute the ease reductions to retain a nice sleeve cap shaping. Finally, check your notch placement on the sleeve and move it to where it should be.

As I stated before, I probably did a combination of these three methods so that I didn't do anything too drastic. It will take subtle changes to distribute the ease reductions to retain a nice sleeve cap shaping. Finally, check your notch placement on the sleeve and move it to where it should be.

Any questions?

Melissa wrote some comments on my blog entry A Problem with Cap Sleeves:

I was really excited when I found your blog on the children's sleeve draft from Armstrong's book. I have been working on a project for weeks now and I'm having a lot of trouble with the sleeve. Starting with the Basic Sleeve Draft, I found there was too much ease and took 2cm off the bicep measurement when I read that you take the ease out. But my worry is the shaping of the sleeve cap, it just doesn't look right to me. Even before I took out the ease, it looked like the under arm shaping was really short. When I compare it to bought patterns and the pictures in the book, it just looks like the notches are really low, and there is a very small amount left to go under the arms. I have tried a zillion things and it's been driving me crazy and I hope you might be able to shed some light on my sleeve shaping problem. Thanks so much!I responded:

One thing that is probably causing you trouble is the placement of your notches. The notches should match up with the notches on your bodice. They don't necessarily imply that is where you should start easing. Home sewing patterns use those notches to indicate the start and end of easing and thus some of the confusion.This is my promised tutorial. Even though I prefer the Armstrong shaping for cap sleeves, it still leaves too much ease. If you draft the sleeve exactly as outlined in her book, you will have to correct your draft by reducing or removing that ease. On page 68 (second edition) she explains that a sleeve should measure 2 inches bigger than the bicep and have an average of 1.5 inches of sleeve cap ease. On pages 69-70 she illustrates how to reduce/add ease to your sleeve. As I have stated before 1.5 inches of ease is simply too much. Some fabrics require 0.25 to 0.5 inches of ease, but not much more. Armstrong does use the notches to indicate easing. If your sleeve has no ease then the notches are just match points.

And just as an aside, There is more than one way to remove ease. You can lower the sleeve cap, fold out extra (like a tuck), or shorten the bicep at the underarm seam. I'm sure I did some combination of the above.

Just a few more words before you get to the drawings. This is just my method - Armstrong's is similar. My hope is to just illustrate the principle and not hard fast rules. You can have ease, if you choose, thus the tutorial is on how to reduce or remove the ease. You can use this same method to fix the patterns from the Big 4 - which notoriously have too much sleeve cap ease.

Before you can remove/reduce sleeve cap ease, you need to know how much ease the sleeve already has. To do this you need to "walk" the sleeve cap along the armscye - without seam allowances. This is one of the few times I actually remove seam allowances when pattern making because they actually might get in the way. Align the center sleeve notch with the shoulder seam and walk the pattern along until you get to the underarm seam. Armstrong does this procedure just the opposite by starting at the underarm seam and moving toward the shoulder. Either way will work and her method is probably better. I usually do this in a CAD environment and my brain says start at the shoulder. It doesn't really matter so do what you think is right.

Before you can remove/reduce sleeve cap ease, you need to know how much ease the sleeve already has. To do this you need to "walk" the sleeve cap along the armscye - without seam allowances. This is one of the few times I actually remove seam allowances when pattern making because they actually might get in the way. Align the center sleeve notch with the shoulder seam and walk the pattern along until you get to the underarm seam. Armstrong does this procedure just the opposite by starting at the underarm seam and moving toward the shoulder. Either way will work and her method is probably better. I usually do this in a CAD environment and my brain says start at the shoulder. It doesn't really matter so do what you think is right. More walking.

More walking. Still walking. You can see at this point that my underarm notches meet up. This won't be true in the real world - this is just how my drawing ended up. When I am done altering the sleeve, I move the notches where I need them to be. Right now my goal is to get the sleeve cap and armscye to be the same distance. This is where the Armstrong method might work better for you as the underarm notches don't move.

Still walking. You can see at this point that my underarm notches meet up. This won't be true in the real world - this is just how my drawing ended up. When I am done altering the sleeve, I move the notches where I need them to be. Right now my goal is to get the sleeve cap and armscye to be the same distance. This is where the Armstrong method might work better for you as the underarm notches don't move. Finally done walking. Now measure any of the sleeve cap that is left over. This is how much ease you have on the front. Yes, sleeves have a front and a back and I only walked my sleeve along the front armscye. You will need to repeat the procedure since most of you will have assymetric sleeves. My sleeves tend to be symmetric for children so I only have to walk the pattern on one side. Make sense? Now that you know how much ease you have, you can decide how much to remove.

Finally done walking. Now measure any of the sleeve cap that is left over. This is how much ease you have on the front. Yes, sleeves have a front and a back and I only walked my sleeve along the front armscye. You will need to repeat the procedure since most of you will have assymetric sleeves. My sleeves tend to be symmetric for children so I only have to walk the pattern on one side. Make sense? Now that you know how much ease you have, you can decide how much to remove. This is where things can get a little fiddly... There are a few different ways to remove sleeve cap ease. I usually use a combination of these methods because I want to maintain a nice sleeve cap shape. Not too flat and not too round. My eyes have been trained to recognize a good sleeve cap shaping and it is not something I can pass along to you. You will have to experiment a little bit to see what works best. Try to keep the convex and concave curves balanced (again, how to explain that?). In this drawing I show two places to reduce ease. The first is to shorten the bicep line by moving in the underarm seam. Armstrong's extra 2 inches is too much for children. It may be too much for adults too. It all depends on your desired fit. The next place to remove ease is to lower the sleeve cap height. With my cap sleeve, I lowered the sleeve cap height at least 1/2 inch and re-drew the cap. Again it depends on your fit and the shape of your sleeve to begin with.

This is where things can get a little fiddly... There are a few different ways to remove sleeve cap ease. I usually use a combination of these methods because I want to maintain a nice sleeve cap shape. Not too flat and not too round. My eyes have been trained to recognize a good sleeve cap shaping and it is not something I can pass along to you. You will have to experiment a little bit to see what works best. Try to keep the convex and concave curves balanced (again, how to explain that?). In this drawing I show two places to reduce ease. The first is to shorten the bicep line by moving in the underarm seam. Armstrong's extra 2 inches is too much for children. It may be too much for adults too. It all depends on your desired fit. The next place to remove ease is to lower the sleeve cap height. With my cap sleeve, I lowered the sleeve cap height at least 1/2 inch and re-drew the cap. Again it depends on your fit and the shape of your sleeve to begin with. Another way to reduce sleeve cap ease is to split the pattern and overlap it - similar to these drawings (remember I am only working on the front side so don't forget to do the back). Redraw the sleeve cap. This method reduces the bicep but may help preserve the cap shaping.

Another way to reduce sleeve cap ease is to split the pattern and overlap it - similar to these drawings (remember I am only working on the front side so don't forget to do the back). Redraw the sleeve cap. This method reduces the bicep but may help preserve the cap shaping. As I stated before, I probably did a combination of these three methods so that I didn't do anything too drastic. It will take subtle changes to distribute the ease reductions to retain a nice sleeve cap shaping. Finally, check your notch placement on the sleeve and move it to where it should be.

As I stated before, I probably did a combination of these three methods so that I didn't do anything too drastic. It will take subtle changes to distribute the ease reductions to retain a nice sleeve cap shaping. Finally, check your notch placement on the sleeve and move it to where it should be.Any questions?

January 21, 2008

Grading Pants Notes pt. 3

The following is my final entry on grading infant-toddler pants. Having a copy of the Jack Handford grading manual will be helpful in understanding what these notes mean, especially for this last entry. Hopefully you have at least read the introduction and the instructions for grading a bodice. If you don't have a copy of the book, save these notes anyway - they may come in handy. Part 1 contains an explanation of direction arrows, Part 2 explains notation.

My infant-toddler pants are between knee and mid-calf length. I designed them to peek out just below the skirts of my dresses without distracting from the overall look of the dress. I wanted the trim of the pants barely visible below the skirt hem. So what should be the length grade of my pants?

At the top of the page for the pant grade (i.e., pg 218), Handford states that the grade for various lengths can be determined by studying the grading chart and diagram. The grading chart contains instructions for grading ankle length pants. I don't know why, but it wasn't obvious to me what grade steps to alter. I ended up doing the ankle length grade and decided it was grading to much. Did I mention that I ended up grading my toddler pants three times? Anyway, if you want to grade shorts, or any other length, these are the steps to alter:

Move #5 and #9 (up) is the knee length grade.

Move #6 and #8 is the ankle length grade.

If you want knee length shorts, skip moves #6 & #8. If you want mid-calf length, you could try splitting the difference between the knee length and ankle length grade. Any other lengths will be some variation on the above mentioned moves. If the length is closer to the ankle, follow the ankle grade and vice versa for shorter styles. In other words, these moves are flexible and depend on the style you are grading. It also depends on the personal preference of the individual grader. I graded my pants using the knee-length grade.

One reason I had a little bit of difficulty with determining the length grade has to do with my computerized grading experience. Moves 5 & 6, for example, can be combined in one grading point. The grading of children's patterns can be simplified because the shapes and growth is simpler in some ways. Since you can select an individual grading point and put in relative changes, the moves are interpreted a little bit differently. I am a self-taught grader and it takes me a bit more effort to determine my approach.

Any other question on grading pants? I hope these notes are helpful.

My infant-toddler pants are between knee and mid-calf length. I designed them to peek out just below the skirts of my dresses without distracting from the overall look of the dress. I wanted the trim of the pants barely visible below the skirt hem. So what should be the length grade of my pants?

At the top of the page for the pant grade (i.e., pg 218), Handford states that the grade for various lengths can be determined by studying the grading chart and diagram. The grading chart contains instructions for grading ankle length pants. I don't know why, but it wasn't obvious to me what grade steps to alter. I ended up doing the ankle length grade and decided it was grading to much. Did I mention that I ended up grading my toddler pants three times? Anyway, if you want to grade shorts, or any other length, these are the steps to alter:

Move #5 and #9 (up) is the knee length grade.

Move #6 and #8 is the ankle length grade.

If you want knee length shorts, skip moves #6 & #8. If you want mid-calf length, you could try splitting the difference between the knee length and ankle length grade. Any other lengths will be some variation on the above mentioned moves. If the length is closer to the ankle, follow the ankle grade and vice versa for shorter styles. In other words, these moves are flexible and depend on the style you are grading. It also depends on the personal preference of the individual grader. I graded my pants using the knee-length grade.

One reason I had a little bit of difficulty with determining the length grade has to do with my computerized grading experience. Moves 5 & 6, for example, can be combined in one grading point. The grading of children's patterns can be simplified because the shapes and growth is simpler in some ways. Since you can select an individual grading point and put in relative changes, the moves are interpreted a little bit differently. I am a self-taught grader and it takes me a bit more effort to determine my approach.

Any other question on grading pants? I hope these notes are helpful.

Labels:

Clothing for Children,

Directions,

Fitting,

Grading,

Pants,

Patternmaking,

Proportion,

Sizing

November 09, 2007

Standard Pattern Blocks- Flat vs. Classic

Tiki left some questions in comments and I thought I would address them in a separate blog entry.

My basic blocks are a variation of the flat method. The armholes and shoulders of the front and backs pieces are identical. The body widths match (the long vertical line indicates the center back/front). The flat fit is a little more boxy and loose. My fit is not too boxy, but it does allow for some growth. You can see the fit of this bodice on one of my dresses. The patterns are not too boxy because the side seams do taper inward and my front waist has some curve. Aldrich's patterns have a straight side seam and waistline. BTW, I am not done refining the shape of this pattern - I am considering narrowing the shoulders and reducing the armhole. You have to start somewhere with your patterns, and they will evolve as you refine your fit.

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes.

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes.

This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.

This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.

There is a relationship with children's body shapes and the flat method. Young children are simple round cylindrical shapes until about the age of 5 and it makes sense to keep the patterns simple.

This is a topic I am still researching and trying to understand. I hate to label flat blocks as a standard because there are several possible methods that may be considered "right" or the "standard". Pattern making is considered a technical, rigid system, but don't be afraid to do things your way. I learn things from those who do not have formal training and are not afraid to do things a little different. Sure there are certain accepted standards for labeling patterns or placing notches. Acceptable shaping and fit is open to interpretation.

I am reworking some of my patterns and have both Aldrich's and Armstrong's books as well. As you mentioned, I have noticed that my own kids' clothes from various manufacturers are drafted "flat" as Aldrich describes it, with the front and back patterns basically identical except for the neckline, but was wondering if you could explain more why that is the standard.Here is a picture of what Tiki is talking about. Aldrich is the only other person I know of that addresses this topic. It is true that most childrenswear manufacturers work off of flat blocks, especially for infants. Aldrich only presents it for infant casual clothing. But I have seen variations of the idea spanning all children's sizes.

My basic blocks are a variation of the flat method. The armholes and shoulders of the front and backs pieces are identical. The body widths match (the long vertical line indicates the center back/front). The flat fit is a little more boxy and loose. My fit is not too boxy, but it does allow for some growth. You can see the fit of this bodice on one of my dresses. The patterns are not too boxy because the side seams do taper inward and my front waist has some curve. Aldrich's patterns have a straight side seam and waistline. BTW, I am not done refining the shape of this pattern - I am considering narrowing the shoulders and reducing the armhole. You have to start somewhere with your patterns, and they will evolve as you refine your fit.

I have read the discussion of armhole and sleeve shaping from Kathleen's blog and book and was wondering if the standard in the children's wear industry is due to simplicity in drafting, etc (perhaps because there is more ease built into the design of the garment itself) or if there is a specific anatomical/physical reason that makes drafting the asymmetrical sleeve/armhole unnecessary in children's wear. I guess, in other words, is that only the standard in loose children's garments or would drafting a more fitted children's garment with the same symmetrical sleeve still be correct/standard?I can't say for sure why this is the standard. It is definitely not something I learned in school, but rather on the job. Tiki's instincts are probably right. There is a simplicity in the drafting of flat pattern blocks, and it does save some time. There is a physical limitation too. The smaller the size, the less practical it becomes to draft a classic block. A flat block gives some wearing ease and allows for growth. Children, after all, grow and a little extra ease allows the clothing to be worn longer. And yes, you can draft a more fitted bodice block with symmetrical armholes/sleeves. That is what I did with my patterns because it is what looked right to me. Here are some pictures of a classic, fitted block with asymmetric armholes (click on images for a better view).

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes.

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes. This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.

This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.There is a relationship with children's body shapes and the flat method. Young children are simple round cylindrical shapes until about the age of 5 and it makes sense to keep the patterns simple.

I'm having difficulty understanding from Aldrich's book what makes the "flat" block or "classic" block more appropriate for a particular style, so I wondered what was standard practice here in the industry. I hope this makes sense.I look at it this way. Flat blocks are good for casual styles, like t-shirts. Classic blocks are good for more formal looks. Flat blocks are good for infant sizes, classic for older. Your fit and look defines your design and you can opt for either method. Usually I see a modified classic block for fit, but with symmetrical armholes and shoulders (perhaps more of a convention rather than a standard). I have seen some designers use only classic blocks and others only flat. Really, the decision is up to you.

This is a topic I am still researching and trying to understand. I hate to label flat blocks as a standard because there are several possible methods that may be considered "right" or the "standard". Pattern making is considered a technical, rigid system, but don't be afraid to do things your way. I learn things from those who do not have formal training and are not afraid to do things a little different. Sure there are certain accepted standards for labeling patterns or placing notches. Acceptable shaping and fit is open to interpretation.

November 01, 2007

A Problem With Cap Sleeves

Over the last couple of months I have struggled with drafting a toddler cap sleeve. For whatever reason, my infant cap sleeve came off without a hitch. I tried some quick and dirty pattern making by grading the infant sleeve up to 24M and using it as my toddler base. The shaping just didn't work and I had to actually draft a 3T sleeve. I used the opportunity to compare draft instruction between Aldrich and Armstrong

and Armstrong and these are my results.

and these are my results.

The actual draft instructions for either cap sleeve are fairly simple and easy to draft. Even so, I didn't like the shaping and resultant styles of either sleeve. I'll try to explain the differences of each. I had a stronger preference for the Armstrong version, but I still modified hers considerably.

The top sleeve is the Aldrich version, the bottom my modified Armstrong sleeve. The Aldrich sleeve is very straight - such a sleeve results in a large sleeve cuff opening. Her sleeve is not a fitted cap sleeve. The instructions were easy to follow, I just had a styling disagreement.

I much prefer a fitted cap sleeve. The basis of the sleeve draft must start with a regular sleeve block. Just draw in a style line similar to what you see in the photo for the shaping at the hem. There are some minor refinements detailed in the Armstrong book. The problem with the Armstrong draft is that the sleeve cap height was too high for a toddler. I decreased the cap height by about a good 1/2". Walk the sleeve cap along the armscye and adjust any length differences. Armstrong states there should be 1-1 1/2" of ease in the sleeve cap, which is simply too much. My sleeves have virtually no ease because I removed it. Sometimes the fabric calls for 1/4-1/2" of ease, but not anymore. A sewing operator will return a bundle with too much sleeve cap ease. It is just too difficult to sew in an industrial sewing. And in IMO, it doesn't do anything for fit or wearing ease. Armstrong's draft instructions are easy to follow and you can make any adjustments you prefer after you have the shape you want.

If you look closely, you will notice that my sleeves are symmetrical. This is because my bodice armhole shapes are identical for the front and back. This is typical in the industry for infant and toddler styles. In older children, this is not true and Aldrich's basic sleeve drafts illustrate the differences very well. Kathleen Fasanella has blogged much on the proper shaping of sleeve caps.

Here is a sewn sample. On the right is the Aldrich cap sleeve and my modified Armstrong sleeve is on the left. Can you see the difference in the sleeve shaping and cuff openings? The sleeve on the right is good for t-shirts and casual styles. The sleeve on the left is better for more formal, fitted styles. I have a few minor refinements to make and at least one more sew test and I will have my toddler cap sleeve done! (I am debating on adding 1/4" back to the sleeve cap height, overall I like it).

Here is a sewn sample. On the right is the Aldrich cap sleeve and my modified Armstrong sleeve is on the left. Can you see the difference in the sleeve shaping and cuff openings? The sleeve on the right is good for t-shirts and casual styles. The sleeve on the left is better for more formal, fitted styles. I have a few minor refinements to make and at least one more sew test and I will have my toddler cap sleeve done! (I am debating on adding 1/4" back to the sleeve cap height, overall I like it).

Either book will get you a basic cap sleeve. My eyes prefer the fitted style. Any questions? Anyone need draft instructions?

The actual draft instructions for either cap sleeve are fairly simple and easy to draft. Even so, I didn't like the shaping and resultant styles of either sleeve. I'll try to explain the differences of each. I had a stronger preference for the Armstrong version, but I still modified hers considerably.

The top sleeve is the Aldrich version, the bottom my modified Armstrong sleeve. The Aldrich sleeve is very straight - such a sleeve results in a large sleeve cuff opening. Her sleeve is not a fitted cap sleeve. The instructions were easy to follow, I just had a styling disagreement.

I much prefer a fitted cap sleeve. The basis of the sleeve draft must start with a regular sleeve block. Just draw in a style line similar to what you see in the photo for the shaping at the hem. There are some minor refinements detailed in the Armstrong book. The problem with the Armstrong draft is that the sleeve cap height was too high for a toddler. I decreased the cap height by about a good 1/2". Walk the sleeve cap along the armscye and adjust any length differences. Armstrong states there should be 1-1 1/2" of ease in the sleeve cap, which is simply too much. My sleeves have virtually no ease because I removed it. Sometimes the fabric calls for 1/4-1/2" of ease, but not anymore. A sewing operator will return a bundle with too much sleeve cap ease. It is just too difficult to sew in an industrial sewing. And in IMO, it doesn't do anything for fit or wearing ease. Armstrong's draft instructions are easy to follow and you can make any adjustments you prefer after you have the shape you want.

If you look closely, you will notice that my sleeves are symmetrical. This is because my bodice armhole shapes are identical for the front and back. This is typical in the industry for infant and toddler styles. In older children, this is not true and Aldrich's basic sleeve drafts illustrate the differences very well. Kathleen Fasanella has blogged much on the proper shaping of sleeve caps.

Here is a sewn sample. On the right is the Aldrich cap sleeve and my modified Armstrong sleeve is on the left. Can you see the difference in the sleeve shaping and cuff openings? The sleeve on the right is good for t-shirts and casual styles. The sleeve on the left is better for more formal, fitted styles. I have a few minor refinements to make and at least one more sew test and I will have my toddler cap sleeve done! (I am debating on adding 1/4" back to the sleeve cap height, overall I like it).

Here is a sewn sample. On the right is the Aldrich cap sleeve and my modified Armstrong sleeve is on the left. Can you see the difference in the sleeve shaping and cuff openings? The sleeve on the right is good for t-shirts and casual styles. The sleeve on the left is better for more formal, fitted styles. I have a few minor refinements to make and at least one more sew test and I will have my toddler cap sleeve done! (I am debating on adding 1/4" back to the sleeve cap height, overall I like it).Either book will get you a basic cap sleeve. My eyes prefer the fitted style. Any questions? Anyone need draft instructions?

Labels:

Cap sleeve pattern,

Clothing for Children,

Fashion,

Fitting,

Patternmaking,

Sleeve,

Style

June 13, 2007

Resizing Vintage Patterns versus Grading

The same reader from the previous post also asked:

Also, I found some info on resizing vintage patterns http://www.sensibility.com/pattern/resizepattern.htm thought it might be of interest.I checked out the link and I do like the website. However, Jenny's pattern resizing tutorial is mis-named. She actually is describing a grading process. It is not a very precise method, but perhaps it would work for a custom or one-time project. I would still encourage my readers to learn a better method, especially for preparing patterns for production.

The idea of re-sizing patterns implies there is an inherent sizing problem which should be solved. If you buy a commercial pattern and you need a longer waist, then you would resize the pattern by slashing and spreading it longer to the required measurement. Jenny does describe such a process at the end of her tutorial.

Jenny goes one step further and shows how to alter an adult pattern into a children's pattern. The method probably will work, but it will require too much fiddling. Why not take a basic block the size you need and draft the same style?

I don't think I am being too hard on Jenny. She does have a nice website. Just realize her perspective is geared more to costumers and others who don't want to be bothered with details.

Labels:

Fitting,

Grading,

Measurement charts,

Patternmaking,

Refashion,

Sizing

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)