In the fashion industry a second is an item with a few defects that can still be worn or used. If there are seconds, then there are firsts though we don't call them that. We may call them first quality, though I rarely hear that term either. The word quality, all by itself, is a controversial term with various meanings attached to it. If there are firsts and seconds, then there are also thirds.

The goal of any company is to produce goods without any defects for the least amount of money possible. But as we all live in the real world, defects happen. I've worked for three different companies and how each handled defects were roughly the same. Each company came up with a ranking system to evaluate product during production and as it came off the line. Each ranking was called something a little different though they conveyed the same meaning. The qualification for each ranking varied and the product that fell into each ranking was handled differently. Here is a brief break down.

First - top quality goods with no obvious defects

Second - goods with X number of defects that may or may not be repaired, but still wearable or usable and can be sold on a secondary market.

Third - goods with sufficient number of serious defects to render the item unwearable or usable. These goods may be sold for scrap and may be called rejects.

Quality can be subjective and that can cause problems not only in production but in the retail sector. A first quality item can be rendered second or third after it's first wearing and washing. In that case, was the item truly a first quality item? Perhaps not. Likewise, a second can be repaired sufficiently to make it a first quality item. But is it financially feasible to repair a second to make it a first? These are all questions that individual companies must deal with as they develop and sell product. In order to not get too long-winded on this subject, let's look at something I recently purchased at the thrift store.

This is a cute knit top that I found at a thrift store for a few dollars. It looked pretty good when I tried it on in the dressing room, but as usual the lighting was bad and I missed some obvious problems. Once home I tried it on again and immediately saw a problem with the gathers on the neckband. I also noticed the brand label and content tag were off center. Also the elastic on one of the sleeve hems was pulling away. It is true that most thrift store clothes are previously worn and I have no doubt this shirt fit that category. But because of the defects, I think this shirt started life as a second and was likely sold at an outlet store or other secondary market.

A closer look reveals the problem on the neckline. There is some fabric caught in the seam. Unfortunately, I did not take any pictures of the problem from the other side, but the fabric caught in the stitching is more obvious.

This style of neckline would be difficult to sew, especially in a factory. First, each gathered area was pre-gathered by applying 1/4 inch clear elastic - stretched between notches. Next, the operator prepares the neck band. The tie and neckband are one piece. The tie portion is sewn and turned out and the rest of the neckband is folded in half. Hopefully there were notches to help the operator position the neck band on the neck, otherwise it would be easy to skew the neckband. Anyway, the operator matches up the neckband to the neckline, starting the sewing on the left side neck. The neckband would be on top and the neckline on bottom. The operator has to match the pre-gathered section from underneath to meet a match point on the band, catch enough of the seam under the

foot securely and then stitch the pre-gathered section to the neckband. Hopefully there is another notch to indicate where the pre-gathered section should end. The sewing continues around the neck to the right side, where there is hopefully another notch to indicate where the next pre-gathered section should start. The neckline is then finished off, overedging the center front neck which is left unattached from the neckband. This small section is later topstitched down. Finally, the next operator would place the brand and size label to the back neck with a single needle machine within the seam allowance of the neckband/neckline.

The most difficult part of this whole sequence of steps would be where the operator starts attaching the neckband on the left side. The pre-gathered section is not stable and will move around as the pieces are placed under the foot. This is what happened here. Some additional fabric worked its way under the foot as the sewing began. The label placement would be difficult because the operator would have to guess where center back is and place the labels on a knit top that likes to move around.

This type of defect would have been difficult to repair in a factory. The elastic and two rows of stitching would be time consuming to undo and redo and look good. The poor placement of the brand labels would have been a second strike. The top was still wearable though and likely sold as a second or at a steep discount. I imagine there were quite a few seconds on this style....

Anyway, I was able to repair this top. I carefully unpicked the band with my fingers crossed that none of the shirt was cut when it was stitched. Luckily it wasn't. I removed some of the elastic in the affected area (it wasn't worth redoing the whole gathered area with the elastic), and regathered the neckline with a needle and thread. I then basted the neckband and neckline together to double check it was all right and stitched it back together. Almost as good as new - at least you can't tell there had ever been a problem.

Showing posts with label Definitions. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Definitions. Show all posts

October 13, 2014

April 29, 2014

Grading vocabulary - Nest and stack point

As I have attempted to learn how to code (computer programming), I have been stymied by one simple problem. Vocabulary. Most programming manuals or tutorials assume the learner has some basic knowledge about programming and skip explaining essential skills or words. This is even true of the manuals designed for complete idiots and absolute beginners. One good example in the programming world is the word compiler. I understand it on a basic level as a set of instructions that tells the computer how to link various files to create the executable software program.* There are various ways to deal with compilers depending on the programming language and platform used. I didn't know what compilers there were, which to use, how to write the instructions, etc. All I could find was some pretty lousy examples that I could copy and paste and they magically (or not) worked. I could present dozens of examples of this disconnect as I've stumbled my way through working on SodaCAD.

Grading manuals are similar, at least the ones I have used. They lack sufficient or clear explanations of the most basic of terms. Often times the manual writers skip sizing theory and jump to demonstrating their preferred grading method. This includes the much revered Jack Handford grading manual, the manual I still use and recommend today. Handford's book was the first that helped me understand grading but I recently reviewed the book and noticed the notations I made where I was confused.

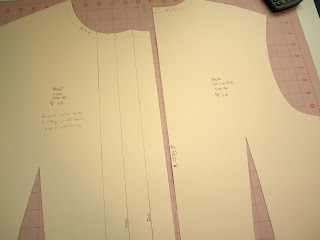

One of my goals in writing my grading manual is to include a Grading 101 section. The above drawing is the illustration for two terms.

Nest - pattern pieces within a size range that are stacked along a common point or line. Indicated here by the horizontal line and star.

Stack point - the point at which pattern pieces are aligned, generally located in the middle of the piece but may be located elsewhere (indicated by the star). In CAD grading, the stack point may also be called the point of origin and can be easily moved as needed.

I'm still working on my vocabulary list and guide. If there is a term you have heard and would like explained, please leave a comment below

*I realize I probably just used some vocabulary that the readers of this blog might not know. In any event, it illustrates the problem.

Grading manuals are similar, at least the ones I have used. They lack sufficient or clear explanations of the most basic of terms. Often times the manual writers skip sizing theory and jump to demonstrating their preferred grading method. This includes the much revered Jack Handford grading manual, the manual I still use and recommend today. Handford's book was the first that helped me understand grading but I recently reviewed the book and noticed the notations I made where I was confused.

One of my goals in writing my grading manual is to include a Grading 101 section. The above drawing is the illustration for two terms.

Nest - pattern pieces within a size range that are stacked along a common point or line. Indicated here by the horizontal line and star.

Stack point - the point at which pattern pieces are aligned, generally located in the middle of the piece but may be located elsewhere (indicated by the star). In CAD grading, the stack point may also be called the point of origin and can be easily moved as needed.

I'm still working on my vocabulary list and guide. If there is a term you have heard and would like explained, please leave a comment below

*I realize I probably just used some vocabulary that the readers of this blog might not know. In any event, it illustrates the problem.

December 02, 2011

Understanding basic block patterns : a few definitions

Shari asked me some questions about basic block patterns.

A basic block pattern is a pattern from which all other styles are based. Sometimes they are derived from the original drafts created from body measurements with instructions from a pattern making manual. Sometimes not. A basic block pattern can also be the patterns from an approved style as described above.

Just as an example, we can look at my recent blouse making venture. After a bit of testing, the pattern pieces for that blouse have become my basic block patterns for future blouse styles. I cut them out of tag board so I can trace them off, either on fabric for cutting or on paper for drafting a new style. The pieces have seam allowances and notes to help for future construction.

Pattern makers in the industry do not draft from zero every season. We trace off existing pattern pieces (blocks) and modify them. Over time we create a library of pattern pieces that can be mixed and match for a variety of styles.

So what are the options?

1. Draft your own patterns from body measurements using a pattern making manual. This is the most time consuming option, but ultimately the only way to ensure the fit you want.

2. Hire a pattern maker to do it for you. Probably the most expensive option. You will need to be prepared with a basic style, body measurements, etc. Expect a bit of back and forth as you refine fit.

3. Adapting commercial sewing patterns*. You can buy a commercial sewing pattern for a similar style but it will require a bit of fixing - actually a lot. Commercial patterns are usually sloppy and are not production ready by any stretch. One exception are Burda patterns which do not have seam allowances, so they will be easier to fix and adapt. Burda has even released their patterns as "open source", which is actually a misnomer. In other words, Burda has released their patterns with the license to use the pattern as you wish. And lest you think that I am encouraging the violation of the copyrights of commercial patterns, please know that the copyright status of patterns are in a legal quandry. In other words, in the U.S. no one can stop you from using the patterns you purchase as you wish, even though many believe they can. The only way to avoid that mess and confusion is to draft your own patterns from scratch.

4. Buy block patterns from someone else. I've never seen any production ready patterns available for sale. That doesn't mean it will never happen. I've even considered selling mine, but I haven't done it yet.

BTW, my blouse patterns were adapted from some Burda patterns and it worked well for the most part. The collar pattern pieces required a lot of work and I still don't have them right, IMO.

*If you buy a commercial pattern to take to a professional pattern maker to fix, you will probably be turned down. Commercial patterns require a lot of work to fix and it is honestly easier to draft a pattern from scratch. Some may turn you down for ethical reasons. Others may turn you down because you may give the impression that you are not ready or prepared to be a professional. I probably would turn you down too. The only way I would use a commercial pattern from a client is as a reference to match fit and styling while using my own block patterns or drafting from scratch.

So pleased I stumbled on you blog - wonderful work by the way! I am keen to start designing kiddies clothing and I am trying to find block patterns and relevant information on using/adapting them, that is not too confusing.The first thing to do is to define the term block pattern. A block pattern is a finished pattern with all seam allowances, notches, notation, etc. The pattern has been tested and approved for fit. It has been used, perhaps, in a style that has proven to be acceptable with customers.

I have got some info on-line and books out of the library but have not

found anything that I am happy with. I am wondering if you could give me any pointers on where to start looking and/or even purchasing basic block templates.

Developing a basic block pattern

A basic block pattern is a pattern from which all other styles are based. Sometimes they are derived from the original drafts created from body measurements with instructions from a pattern making manual. Sometimes not. A basic block pattern can also be the patterns from an approved style as described above.

Just as an example, we can look at my recent blouse making venture. After a bit of testing, the pattern pieces for that blouse have become my basic block patterns for future blouse styles. I cut them out of tag board so I can trace them off, either on fabric for cutting or on paper for drafting a new style. The pieces have seam allowances and notes to help for future construction.

Pattern makers in the industry do not draft from zero every season. We trace off existing pattern pieces (blocks) and modify them. Over time we create a library of pattern pieces that can be mixed and match for a variety of styles.

How to acquire basic block patterns

There is no easy way to acquire basic block patterns. These types of patterns are considered proprietary to the business that developed them so they are rarely for sell. That leaves new designers with a few options and none of them are easy. And perhaps, that is how it should be. I know that sounds harsh, but your patterns will be better if you struggle through the development process yourself. You will come to understand how things should fit and be sewn and know how your patterns work.So what are the options?

1. Draft your own patterns from body measurements using a pattern making manual. This is the most time consuming option, but ultimately the only way to ensure the fit you want.

2. Hire a pattern maker to do it for you. Probably the most expensive option. You will need to be prepared with a basic style, body measurements, etc. Expect a bit of back and forth as you refine fit.

3. Adapting commercial sewing patterns*. You can buy a commercial sewing pattern for a similar style but it will require a bit of fixing - actually a lot. Commercial patterns are usually sloppy and are not production ready by any stretch. One exception are Burda patterns which do not have seam allowances, so they will be easier to fix and adapt. Burda has even released their patterns as "open source", which is actually a misnomer. In other words, Burda has released their patterns with the license to use the pattern as you wish. And lest you think that I am encouraging the violation of the copyrights of commercial patterns, please know that the copyright status of patterns are in a legal quandry. In other words, in the U.S. no one can stop you from using the patterns you purchase as you wish, even though many believe they can. The only way to avoid that mess and confusion is to draft your own patterns from scratch.

4. Buy block patterns from someone else. I've never seen any production ready patterns available for sale. That doesn't mean it will never happen. I've even considered selling mine, but I haven't done it yet.

BTW, my blouse patterns were adapted from some Burda patterns and it worked well for the most part. The collar pattern pieces required a lot of work and I still don't have them right, IMO.

*If you buy a commercial pattern to take to a professional pattern maker to fix, you will probably be turned down. Commercial patterns require a lot of work to fix and it is honestly easier to draft a pattern from scratch. Some may turn you down for ethical reasons. Others may turn you down because you may give the impression that you are not ready or prepared to be a professional. I probably would turn you down too. The only way I would use a commercial pattern from a client is as a reference to match fit and styling while using my own block patterns or drafting from scratch.

December 15, 2009

Metric pattern cutting for children's wear and babywear - 4th Edition

Winifred Aldrich has released an updated edition of her pattern making book. Besides having a much nicer cover design, it reportedly contains a revised organization and emphasis on flat pattern making. I find this change interesting because more and more design entrepreneurs are utilizing flat pattern making today and this confirms my personal experiences in the industry.

From the abstract at Amazon:

Today’s popularity of easy-fitting styles and knitted fabrics means that basic ‘flat’ pattern cutting is used to construct the majority of children’s wear and babywear and this type of cutting is therefore emphasized in this new edition. Shaped blocks and garments, cut to fit the body form, are still included, and are placed in chapters covering some school uniform garments or more expensive fashion or formal clothes.

One primary difference between flat versus fitted pattern making is that the patterns have the same shape for the front and back pieces. For example, the armhole shaping is symmetrical. Creating patterns in this way results in a looser, more casual fit and it is appropriate for a lot of children's clothing. Even so, I see more of a modified flat method in actual use. Patterns are modified so that they aren't quite so boxy and more fitted. Yet, they retain some symmetry between front and back pieces.

October 26, 2009

Do professional pattern makers work with seams on or off the pattern?

Professional apparel pattern makers work with seam allowances on their patterns nearly all the time. It's faster. I would argue it's more precise. This practice goes counter to what most pattern making classes teach. They teach that you must remove the seam allowances and add them back later. I don't know anyone in the industry that works this way. I think the idea is that working with seam allowances one can create variations that lead to fitting problems later. That's simply not true if you check your new pattern against the original block later. (This is assuming you make a copy or rubbing of your original before you start on a new style. But I'm sure you knew that).

If you are drafting by hand, it is time consuming to remove the seam allowances. Pattern blocks are made with seam allowances on. You would have to keep a set of blocks without seam allowances. It would be so easy to mix up seamed and unseamed pattern blocks. Apparel pattern makers leave their blocks seamed and theatre pattern makers or cutters leave their blocks (or rather slopers) unseamed. In fact a block is a finished pattern piece that includes all pattern markings and is seamed.

If you are drafting in CAD, you can turn the seam allowances on and off. You can work on the cutting line or the stitching line. It's a simple matter of hitting a few buttons. BUT, I have found that CAD programs have difficulty in calculating between seamed and unseamed because it involves a complex series of mathematics. So constantly switching between cutting and stitching lines can produce some weird anomalies. (As an aside, weird things can happen with notches on stitching versus cutting lines too). I have found this is true no matter which CAD system you use. So I work with seam allowances on and directly on the cutting line nearly 99% of the time. This means that I keep the seam allowances in mind while I work.

In CAD, it is important to turn the seam allowances off and walk the pattern pieces along the stitching line in a few areas. Collars and necklines is one area that I nearly always check for matching on the stitching line. There are other situations that come up where this important. I learned this the hard way recently.

Next, I aligned the pattern pieces to make sure they match. At this point they did and I assumed all was right. Until I got complaints from the sewing machine operators that things weren't matching up. I had to go back and double check.

I took the seam allowances off the pattern pieces and realigned them. They didn't match, so I redrew the stitching line of the side piece to make sure it matched the center. I added back the seam allowances and realigned the edges.

Your pattern pieces will then look like this and match up in every way possible.

If you are drafting by hand, it is time consuming to remove the seam allowances. Pattern blocks are made with seam allowances on. You would have to keep a set of blocks without seam allowances. It would be so easy to mix up seamed and unseamed pattern blocks. Apparel pattern makers leave their blocks seamed and theatre pattern makers or cutters leave their blocks (or rather slopers) unseamed. In fact a block is a finished pattern piece that includes all pattern markings and is seamed.

If you are drafting in CAD, you can turn the seam allowances on and off. You can work on the cutting line or the stitching line. It's a simple matter of hitting a few buttons. BUT, I have found that CAD programs have difficulty in calculating between seamed and unseamed because it involves a complex series of mathematics. So constantly switching between cutting and stitching lines can produce some weird anomalies. (As an aside, weird things can happen with notches on stitching versus cutting lines too). I have found this is true no matter which CAD system you use. So I work with seam allowances on and directly on the cutting line nearly 99% of the time. This means that I keep the seam allowances in mind while I work.

One Exception

In CAD, it is important to turn the seam allowances off and walk the pattern pieces along the stitching line in a few areas. Collars and necklines is one area that I nearly always check for matching on the stitching line. There are other situations that come up where this important. I learned this the hard way recently.

In this situation, I split a jacket back pattern piece and added corresponding seam allowances along the split line.

Next, I aligned the pattern pieces to make sure they match. At this point they did and I assumed all was right. Until I got complaints from the sewing machine operators that things weren't matching up. I had to go back and double check.

I took the seam allowances off the pattern pieces and realigned them. They didn't match, so I redrew the stitching line of the side piece to make sure it matched the center. I added back the seam allowances and realigned the edges.

The pieces didn't match again. Sewing machine operators also do not like this because they do not know how to align the pieces. In this particular case, the seam allowances are small, so I left the little "dog-ear". It can be difficult to cut those "dog-ears" off by hand when they are really small. It is easier to machine cut. In any event, there are different ways of dealing with this. I show one method below.

Your pattern pieces will then look like this and match up in every way possible.

July 15, 2009

Printing your own fabric pt. 2 : Sourcing Fabric Converters and Printers

Say you are a fashion designer or retailer and you want to custom print your own fabric. You have the skills (or the funds to hire a designer) to create artwork. There are many fashion designers, and even some retailers, who print their own fabric. Off the top of my head Laura Ashley, Ralph Lauren, and Ikea all print their own fabrics, though smaller companies also do it. This is a bit different than my previous blog entry (Printing your own fabric pt. 1), as these individuals are not necessarily textile designers professionally. But as part of a brand image or look, custom prints become necessary.

There is a lot of existing artwork already out there. Freelance textile and graphic designers are available to create the artwork to complement the look of a line. You can also hire graphic designers, though it may be helpful if they have experience in preparing artwork for textile printing. You could even create your own artwork if you have the skills and inclination. You should receive a "strike off" or proof to approve prior to printing. A strike off is a sample of the print and it should represent the actual fabrics, colors, and print registration of the final goods. Make sure to evaluate the strike off thoroughly before committing to a print run.

As a fashion designer, you can contact fabric converters/printers yourself. They can help walk you through the process of preparing the artwork, setting up the repeat and printing the goods. Each printer will vary in their abilities and processes, so don't be deterred if one place is not a good fit. There will likely be a set-up charge to prepare the artwork, so don't be surprised by this.

The biggest question when printing your fabric rests on minimums. How much fabric will you be willing to carry in inventory? Typical minimums average about 3,000 yards. The smaller the quantity, the higher the price per yard. Stateside factories generally require higher minimums. Overseas factories vary - some high, some lower. Some factories may break up the 3,000 yard minimum and allow you to do different colorways of the same print. Others may require 3,000 yards per colorway. Even then, some factories will do less yardage. It is all a matter of research and asking the right questions.

Q: "Can you do custom prints?"

A: "Yes, but it will be a 3,000 yard minimum and 6-8 weeks."

July 13, 2009

Printing your own fabric pt. 1

This may be a future series. I recently talked with someone who has been custom printing his own fabric for a few years now. There are several steps involved with printing your own fabric but it isn't as hard you might think. I am talking about having your designs professionally printed by a fabric converter. There are options that have become available to home hobbyists to print their own fabric, but it is extremely expensive. If you were to take this up as a business, you would need a printer who can print hundreds of yards at an affordable price or you would never make any money.

I have to say I admire some of the up and coming print designers. I admire their skill and ability to create a cohesive collection 1-2x/year. Many of these designers have training in the arts, either the fine arts or graphic design. On top of that, they have some experience working with cloth as seamstresses and pattern makers. I wish I was more skilled at designing prints. I think I could do it but I would need to dedicate a great deal more time to it. Maybe someday I will get up enough gumption to try it and print my own designs.

Traditionally, a textile designer creates their artwork using traditional media - paint and a brush, markers, pastels. At the very least then and now, an artist carries a sketchbook around with them everywhere. They are able to capture patterns and designs in the world around them and translate them into a fabric. They can pick colors suitable for apparel or interior fabrics.

I think most modern textile designers today create their artwork using computer aided design (CAD). Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop are the primary tools. (Free versions include Paint or Gimp, Inkscape). Artwork created in Illustrator or Photoshop is not immediately ready for printing. The artwork must be made into a repeat, created by a special filter or plug-in. The idea is to offset the image 50% horizontally and vertically and fill in with the offset parts. Look for a tiling filter or tool in your program to do it automatically. Once this step is taken, the artwork is ready to be printed by some methods (Spoonflower, for example).

For mass production, the artwork goes through some additional steps though I am sure the technology has changed since I was last exposed to it. There are specialized CAD packages in the industry that some artists use directly or through a trained technician. Artwork is brought into the software and the design is fine tuned through color reduction, recoloring, etc. The design is made into a repeat. The process is rather involved because digital artwork has to be translated into the chosen printing method. And there are several methods out there - heat transfer, roller printing, block, screen printing and digital. The method chosen depends on the converter's ability and/or appropriateness for the print.

If you want to be a textile designer, there are two main approaches. You can create artwork and shop it around to existing fabric manufacturers/printers/converters. Michael Miller, Westminster, and others buy the rights or license artwork from designers. Other designers print and sell their own fabrics. In either case you don't necessarily have to understand all the ins and outs of textile manufacturing and printing. Fabric converters/printers can take your artwork and prepare it for printing (their may be an up-charge or setup fee).

Anyway, more to come as I find this to be an interesting topic....

May 15, 2008

Does your fashion clothing line tell a story?

In a previous blog entry I answered, "What is a line?". That recent blog and other things I have been reading have led me to the next logical question. Does your line tell a story? I partially addressed it in the previous blog.

Some say a line tells a story. That is the more difficult thing to interpret or even observe. Not too many customers care about your source of inspiration unless it is an integral value that they share.

There is a line story and a company story/history/values and some people confuse the two. Does the line story have to reflect the company story? Does each piece have to reflect the company values? How much do the two overlap? Or should they?

A story or narrative describes a sequence of events or parts through the written word or visual depiction. The story contains clues, pieces, or parts that the reader or observer can put together to make a whole picture or concept. At least this is the dictionary definition.

How does this apply to a line of clothes or even a clothing business? You will hear on tv shows like Project Runway that a line should tell a "story". Each piece should be part of a whole. There should be a beginning, middle, and end. If you watch a runway show, the storytelling becomes even more important because a runway show is part entertainment. The runway show of a high-end designer is an easy, not necessarily the best, example. They may start with a strong day piece, maybe some office wear, and usually end on an evening gown. It's as though their customer will be able to visualize wearing each piece as they go through their day.

In the regular old fashion business, the concept becomes more abstract. Still, each piece of your line should look like it belongs to the whole. A sales rep will merchandise your line as though it has a story. They will start with a beginning piece and end with the logical ending piece. They may start with the strongest piece, weakest, or maybe the middle and put it all together so it is most appealing to the buyer. Each buyer may get a different story. A skilled sales rep will know what will appeal best to get the buyer to buy. The entertainment value is overshadowed by the business side of buying and selling.

This why I stated above that the buyer, and even the end consumer, doesn't really care about your source of inspiration or all the blood, sweat, and tears that were shed to complete the line. You shouldn't have to tell them any of that. It isn't relevant. A customer should look at your line and pick out the pieces they like well enough to buy. The story should be subconscious.

A line sometimes has a theme, inspiration, color, style, mood that ties each piece together. If you look at Tea Collection again, you can see an apparent theme. I see beach, sand, and casual. There is a beginning, middle, and end. Do you see it too?

This is not to be confused with your company values, history or story. Now there are some design companies out there that mix their company values and history into each piece. Their story lies on the surface. It is apparent what their clothing stands for, how it was made, and why. There is nothing wrong with doing that, if you choose. But ask yourself, "How long will my story be relevant? How long will the customers care? Will they care?"

What if you create an organic cotton line of screen printed t-shirts for baby with rock star sayings made in a sweatshop free factory? Perhaps those things are part of your core company values or history. How long will this story last before it becomes stale or passe. By mixing your brand, line, and company philosophy too closely, you will limit your company's growth and creativity. If you wear your story on your shirt sleeves, people will eventually tire of you. Such a story can and should be an integral part of you as a designer, not something blasted in their face.

What do you think? How much should your line story and company values overlap?

Labels:

Apparel,

Definitions,

Design,

Fashion,

Fashion Industry,

Line,

Market Research,

Merchandising,

Portfolio,

Story

May 05, 2008

What is a clothing line?

In terms of fashion, a line is a group or collection of 5-7 related pieces. Sometimes it is more. Sometimes the pieces are actually sets because children's lines tend to be sold as sets (bringing the total pieces to around 10-20). The point is that the pieces are related. The pieces have similar colors, tones, mood, feel. From a manufacturing end, the pieces repeat fabrics to minimize and utilize fabric purchases. The clothes have a consistent fit.

Some say a line tells a story. That is the more difficult thing to interpret or even observe. Not too many customers care about your source of inspiration unless it is an integral value that they share. Usually customers care about price, fit, comfort, and finally, "Does it look good?".

To muddy the waters, newer children's designers on Ebay and Etsy do collections based around a fabric grouping. They offer up one of a kind outfits that utilize a particular theme or fabric print. They will call that one outfit or piece a collection. Some of these designers evolve and manage to present a true line. In any event, they are inspiring some RTW collections.

A good example of a well merchandised line can be found at Tea Collection. They do some things really well. They have repeated fabrics. The pieces can be mixed and matched. It has a consistent feel, colors, and look. Each piece looks like it belongs. You could even say it tells a story. Can anyone else see it?

What lines are out there that you like? Post links in comments.

Labels:

Definitions,

Design,

Fashion,

Fashion Industry,

Line,

Manufacturing,

Market Research,

Style

November 09, 2007

Standard Pattern Blocks- Flat vs. Classic

Tiki left some questions in comments and I thought I would address them in a separate blog entry.

My basic blocks are a variation of the flat method. The armholes and shoulders of the front and backs pieces are identical. The body widths match (the long vertical line indicates the center back/front). The flat fit is a little more boxy and loose. My fit is not too boxy, but it does allow for some growth. You can see the fit of this bodice on one of my dresses. The patterns are not too boxy because the side seams do taper inward and my front waist has some curve. Aldrich's patterns have a straight side seam and waistline. BTW, I am not done refining the shape of this pattern - I am considering narrowing the shoulders and reducing the armhole. You have to start somewhere with your patterns, and they will evolve as you refine your fit.

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes.

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes.

This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.

This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.

There is a relationship with children's body shapes and the flat method. Young children are simple round cylindrical shapes until about the age of 5 and it makes sense to keep the patterns simple.

This is a topic I am still researching and trying to understand. I hate to label flat blocks as a standard because there are several possible methods that may be considered "right" or the "standard". Pattern making is considered a technical, rigid system, but don't be afraid to do things your way. I learn things from those who do not have formal training and are not afraid to do things a little different. Sure there are certain accepted standards for labeling patterns or placing notches. Acceptable shaping and fit is open to interpretation.

I am reworking some of my patterns and have both Aldrich's and Armstrong's books as well. As you mentioned, I have noticed that my own kids' clothes from various manufacturers are drafted "flat" as Aldrich describes it, with the front and back patterns basically identical except for the neckline, but was wondering if you could explain more why that is the standard.Here is a picture of what Tiki is talking about. Aldrich is the only other person I know of that addresses this topic. It is true that most childrenswear manufacturers work off of flat blocks, especially for infants. Aldrich only presents it for infant casual clothing. But I have seen variations of the idea spanning all children's sizes.

My basic blocks are a variation of the flat method. The armholes and shoulders of the front and backs pieces are identical. The body widths match (the long vertical line indicates the center back/front). The flat fit is a little more boxy and loose. My fit is not too boxy, but it does allow for some growth. You can see the fit of this bodice on one of my dresses. The patterns are not too boxy because the side seams do taper inward and my front waist has some curve. Aldrich's patterns have a straight side seam and waistline. BTW, I am not done refining the shape of this pattern - I am considering narrowing the shoulders and reducing the armhole. You have to start somewhere with your patterns, and they will evolve as you refine your fit.

I have read the discussion of armhole and sleeve shaping from Kathleen's blog and book and was wondering if the standard in the children's wear industry is due to simplicity in drafting, etc (perhaps because there is more ease built into the design of the garment itself) or if there is a specific anatomical/physical reason that makes drafting the asymmetrical sleeve/armhole unnecessary in children's wear. I guess, in other words, is that only the standard in loose children's garments or would drafting a more fitted children's garment with the same symmetrical sleeve still be correct/standard?I can't say for sure why this is the standard. It is definitely not something I learned in school, but rather on the job. Tiki's instincts are probably right. There is a simplicity in the drafting of flat pattern blocks, and it does save some time. There is a physical limitation too. The smaller the size, the less practical it becomes to draft a classic block. A flat block gives some wearing ease and allows for growth. Children, after all, grow and a little extra ease allows the clothing to be worn longer. And yes, you can draft a more fitted bodice block with symmetrical armholes/sleeves. That is what I did with my patterns because it is what looked right to me. Here are some pictures of a classic, fitted block with asymmetric armholes (click on images for a better view).

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes.

This is a set of classic bodices sized three month. You can see the small armhole - there is little room to draw a nice curve. The back armhole is nearly a straight line. These drafts are based off of Aldrich's book. A classic block would be more appropriate for larger sizes. This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.

This is a corresponding sleeve with an asymmetric sleeve cap. The sleeve cap seems really high and the curves are abrupt, IMO. These blocks could certainly work, but they require more refining. I opted to modify my blocks so they were semi-fitted and flat. The curves are easier and sewing is easier.There is a relationship with children's body shapes and the flat method. Young children are simple round cylindrical shapes until about the age of 5 and it makes sense to keep the patterns simple.

I'm having difficulty understanding from Aldrich's book what makes the "flat" block or "classic" block more appropriate for a particular style, so I wondered what was standard practice here in the industry. I hope this makes sense.I look at it this way. Flat blocks are good for casual styles, like t-shirts. Classic blocks are good for more formal looks. Flat blocks are good for infant sizes, classic for older. Your fit and look defines your design and you can opt for either method. Usually I see a modified classic block for fit, but with symmetrical armholes and shoulders (perhaps more of a convention rather than a standard). I have seen some designers use only classic blocks and others only flat. Really, the decision is up to you.

This is a topic I am still researching and trying to understand. I hate to label flat blocks as a standard because there are several possible methods that may be considered "right" or the "standard". Pattern making is considered a technical, rigid system, but don't be afraid to do things your way. I learn things from those who do not have formal training and are not afraid to do things a little different. Sure there are certain accepted standards for labeling patterns or placing notches. Acceptable shaping and fit is open to interpretation.

August 03, 2007

Are you a draper or a drafter?

In design school the teachers always told us that some students are natural drapers and some are natural drafters. Some students work better with a pencil and paper and others work better with a piece of fabric on a form. I leaned toward the pencil and paper because I prefer to work with numbers. Draping was was more difficult because it seemed less precise. My brain couldn't wrap itself around the concept of turning a drape into a pattern.

Over time draping has become less difficult, but still a challenge. I am getting a good draping exercise by making a slip cover for my old couch. Newer couches have the over-stuffed arms that curve. My couch doesn't have this and I couldn't find a slip cover to fit. A custom cover is $$$. Why not do it myself (with help from a library book on slipcovers)?

I am draping the cover with a "muslin" of green broadcloth and an old sheet.

I just draped the arm and will be moving onto the deck next. This couch has the added difficulty of being a sleeper sofa. We would never have bought a sleeper sofa in a million years but it was given to us and so we use it.

This is the fabric for the couch, a great buy from Wal-Mart. Wal-mart carries upholstery fabric and the price is usually great. BTW, that is our gold rocker. Isn't it lovely?! Unfortunately, the style is too difficult to slipcover and will have to be re-upholstered by a pro.

This is the fabric for the couch, a great buy from Wal-Mart. Wal-mart carries upholstery fabric and the price is usually great. BTW, that is our gold rocker. Isn't it lovely?! Unfortunately, the style is too difficult to slipcover and will have to be re-upholstered by a pro.

Over time draping has become less difficult, but still a challenge. I am getting a good draping exercise by making a slip cover for my old couch. Newer couches have the over-stuffed arms that curve. My couch doesn't have this and I couldn't find a slip cover to fit. A custom cover is $$$. Why not do it myself (with help from a library book on slipcovers)?

I am draping the cover with a "muslin" of green broadcloth and an old sheet.

I just draped the arm and will be moving onto the deck next. This couch has the added difficulty of being a sleeper sofa. We would never have bought a sleeper sofa in a million years but it was given to us and so we use it.

This is the fabric for the couch, a great buy from Wal-Mart. Wal-mart carries upholstery fabric and the price is usually great. BTW, that is our gold rocker. Isn't it lovely?! Unfortunately, the style is too difficult to slipcover and will have to be re-upholstered by a pro.

This is the fabric for the couch, a great buy from Wal-Mart. Wal-mart carries upholstery fabric and the price is usually great. BTW, that is our gold rocker. Isn't it lovely?! Unfortunately, the style is too difficult to slipcover and will have to be re-upholstered by a pro.

Labels:

Definitions,

Draping,

Patternmaking,

Personal Projects,

Skills

July 25, 2007

When do you grade sewing patterns?

Amanda left a comment/question on a previous blog about grading. I thought the answer deserved its own blog entry.

Sloper - a basic fitting pattern used by costumers and home sewing enthusiasts. The pattern does not have seam allowances, which are added later. People who use slopers do all of their pattern making without seam allowances.

Block - A pattern used by fashion designers and pattern makers which forms the basis of future styles. A block is a perfected pattern that has seam allowances. During the pattern making process the seam allowances remain on the pattern.

Many people believe that using blocks (vs. slopers) is an advanced pattern making technique. It's not really. The pattern making process is no different when using blocks, except for not having to add seam allowances. If anything, it saves time in production settings. It is important for the pattern maker to know what the seam allowances are - which are usually drawn onto the pattern anyway. The exception might be CAD patterns which may or may not have the seam allowances drawn. My CAD patterns do not show seam allowances even though they are there. I do all of my pattern making with the seam allowances already on the pattern. Occasionally, I will turn the seam allowances off to check measurements or to match up seam lines of complex pieces. CAD has greatly simplified the manipulation of seam allowances.

Now to answer the question.... Grading should only occur after the pattern has been perfected and the seam allowances have been added. If you add seam allowances after grading you just add more work to your project and you could introduce errors. This is especially true in a factory setting.

Now in theatrical settings, I know this would never occur. A cutter (aka pattern maker) does their pattern making in the size they need and then adds seam allowances during cutting. If they need two sizes of the same style, they will grade the "slopers". Finally, they trace the pattern onto fabric and add the seam allowances while cutting. This system works in the theater but is not precise enough for apparel production.

I have what is probably a stupid question. Do you do the grading before or after you add the Seam Allowance to the sloper? Part of my brain says before because you are likely to get a better line, the other says after as it would be easier. I am loving your blog, thank you so very much.Amanda, not a stupid question at all. The only stupid question is the one not asked. There is a lot of confusion about grading and the difference between a sloper and a block. Let's throw some definitions out and then I'll answer your question.

Sloper - a basic fitting pattern used by costumers and home sewing enthusiasts. The pattern does not have seam allowances, which are added later. People who use slopers do all of their pattern making without seam allowances.

Block - A pattern used by fashion designers and pattern makers which forms the basis of future styles. A block is a perfected pattern that has seam allowances. During the pattern making process the seam allowances remain on the pattern.

Many people believe that using blocks (vs. slopers) is an advanced pattern making technique. It's not really. The pattern making process is no different when using blocks, except for not having to add seam allowances. If anything, it saves time in production settings. It is important for the pattern maker to know what the seam allowances are - which are usually drawn onto the pattern anyway. The exception might be CAD patterns which may or may not have the seam allowances drawn. My CAD patterns do not show seam allowances even though they are there. I do all of my pattern making with the seam allowances already on the pattern. Occasionally, I will turn the seam allowances off to check measurements or to match up seam lines of complex pieces. CAD has greatly simplified the manipulation of seam allowances.

Now to answer the question.... Grading should only occur after the pattern has been perfected and the seam allowances have been added. If you add seam allowances after grading you just add more work to your project and you could introduce errors. This is especially true in a factory setting.

Now in theatrical settings, I know this would never occur. A cutter (aka pattern maker) does their pattern making in the size they need and then adds seam allowances during cutting. If they need two sizes of the same style, they will grade the "slopers". Finally, they trace the pattern onto fabric and add the seam allowances while cutting. This system works in the theater but is not precise enough for apparel production.

Labels:

Definitions,

Grading,

Patternmaking,

Sewing terms,

Sizing,

Technical Design,

Tutorials

January 26, 2007

Grading Stack Points

I am going to try and get back to my grading explanations today. My head is a bit fuzzy after a long week and an especially late night. To review, just click on the grading category link to the right. Click on the picture for a bigger view.

The diagram on the left shows three possible grading examples. This is a basic front bodice pattern piece that is folded in half. Each example is called a nest meaning each size is stacked on top of each other from smallest to largest. The stars represent the point of origin for each grade. The numbers at each point correspond to a grade rule. I will briefly explain each of these items below.

By laying your graded patterns on top of each other in a nest, you can easily see if your pattern is grading proportionally. The stars not only show the point of origin, but the stack point. You can stack your patterns in three general areas and have the grade look different each time. In computerized grading, you can move your stack point anywhere you choose and the grading software will update your grades automatically. For consistency's sake, it is important to determine before you start grading where your stack point/grading point of origin will be.

Each stack point will cause your grading to look different. Most of the grading world uses Example 1. The point of origin is placed in the center of the pattern pieces and growth occurs in all directions. In Example 2, the stack point is placed at the center front waistline and growth occurs to the side and upwards to the neck. Example 3 is the same result as 2, but placed at the center front neck.

I prefer Example 3 and all of my patterns are generally graded this way. It makes the most sense to me and the grade rules are simpler. Most of the proportional changes between sizes occur this way in nature. A person's neck doesn't actually move upward in each size, but rather their waist moves down. Perhaps this is just how my mind works. In any event, you can choose which ever point makes the most sense to you.

I have been using the term grade rules rather loosely in my previous grading articles. Grade rules refer to measurement charts broken down into grade steps. Grade rules can also refer to the actual change that occurs at a point. In the drawings above, I have numbers assigned to each point. Those numbers can refer to a grade rule. For example:

Rule X,Y changes

- 0, 0

- 1/8, 1/8

You can create a chart like the one above, if you prefer. This method is used in computerized grading and each grade rule is placed in a grade library (specific to a size range). Once a style is ready to grade, you simply apply a rule to each point and the pattern pieces will stay graded regardless of pattern changes. It is less helpful when hand grading and may make things more complicated. To be honest, I rarely use grade libraries when computer grading. They can speed things up if you have consistently similar styles. However, things always need tweaking, so I prefer to manually manipulate the grade at each point. Most grading software will allow you to assign a grade rule from a library and still manually edit the point. The computer will begin a grade command by starting with rule #1 and working around through each point. Rule 1 is almost always set as (0,0) and it should always be your stack point.

When hand grading, you should start your grading at your stack point. Once that is set, you then move to the next point, say the neck-shoulder point and mark all of the changes there. Work counter-clockwise (or vice versa, if you choose), around to each point. Setting up a consistent method will help you keep things straight.

Ok. Enough explanation. Decide on your stack point and get ready to grade.

Labels:

Definitions,

Grading,

Patternmaking,

Sewing terms,

Technical Design

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)