I am currently in the process of rewriting this article for another project. A lot of what I wrote in 2006 is a reflection of my thinking back then. I have since refined my thoughts which will be published later. So please consider this article a bit out-of-date.

One designer asked me two fundamental questions. At the time I wasn't sure how to answer them. The first is really a grading question and the second a sizing standard. Both are related. To keep things simple, I will start with the sizing standard question.

"Why are there so many sizes for children's clothing?"

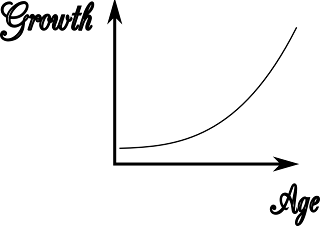

Because children grow. Ok. That is the easy way out. The truth is that children grow and manufacturers try to have a range of sizes to choose from.

The other half of the question was, "Can we have fewer sizes?"

This is a much more complicated answer. Because children's clothing can cover such a wide range, it is possible to have a lot of sizes. One company I worked for produced clothing from Preemie to a size 16 - not including the plus sizes. When you break this down it looks like this:

Preemie, NB, 3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M, 24M, 2T, 3T, 4T, 4, 5, 6, 6x, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16.

This is a whopping 21 sizes! This complicates bookkeeping and sales information incredibly. If you create a style in one colorway, then each size will have its own SKU (stock keeping unit). If you add a colorway, then each size in this style can have two SKU's - one for each color. The company wanted to try and reduce the number of SKU's each season. This particular company produced a new line every 4 months which consisted of dozens of new styles. Thinking about it can give anyone a headache.

To reduce the number of sizes, you have to either combine some of the sizes into ranges and eliminate some duplication. The duplication is the easiest to see first. There is very little difference between a 24M and a 2T. A 24 month old child is essentially a 2 year old. The

T simply means that ease is added to the pant area for a diaper.* Most 24 month old children and 2T children are still wearing diapers, so there should little to no difference in the patterns there.

*I'm not sure where the idea that the T in the size 2T implied the size included diaper ease. I repeated this idea because it was all I knew at the time. After a lot of research, I now believe this idea is a myth that has been perpetuated around the internet. I have found no size study information that supports this idea. Rather it has become a standard custom to refer to toddler sizing in this way. As a pattern maker I always included ease for a diaper in the toddler sizes because they wear diapers! The ease is not much more than what is needed for wearing pants anyway. Diapers do not add much bulk these days. Perhaps in years gone past in the age of cloth diapering, it was more of a concern.

The other likely duplication is the 4T and 4. Again these sizes overlap with only a slight difference in the pant area for a diaper. Most four year olds are potty-trained, although it is possible that some are not. In any event, if you manufacturer girl's dresses, this is another area where sizes could be combined. Some companies have started putting out a 5T, but it would be unusual to find a five year old wearing a diaper.

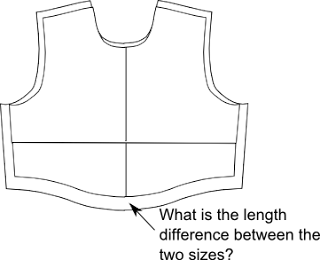

The next size duplication looks like the 6 and 6x. In this case, there is a fitting difference introduced. There should be little girth difference in the patterns, but there will be a length difference. A 6x is a taller size for a 6 year old. Some retailers combine the 6x with a 7. This is where it would be important to know your customers before eliminating or combining sizes.*

*(Please note that this paragraph has been modified. I made a big assumption that was just wrong stating that the size 6x is a plus size version of the size 6. This isn't true. It is a taller version of the size 6. In any event, the paragraph above has been edited with the correct information).

So now our sizing looks like this:

Preemie, NB, 3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M, 24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16.

And this is where I have to interject. Retailers, and especially big box retailers, do differentiate the sizing of the patterns on the sizes we just combined. A 2T is just a little bit bigger than a 24M, even though it really shouldn't be. Consumers have become accustomed to this type of sizing system and so have the technical designers in the business. In other words, don't expect any big changes anytime soon. This proposal is a way to simplify things. You are more likely to find a simplified sizing standard in boutique or specialty stores.

Ok, back on track now. The next step is to create a range of sizes. This is simplest in the infant sizes and another grey area. Every major manufacturer has come up with their own size range break-down, and it really is all over the place.

I really like how JcPenney has broken down their infant size range:

Newborn, 0-3M, 6-9M, 12M, 18M, 24M/2T

The nice thing about this sizing standard is that there are no overlapping of sizes.

Some companies will create a range like this:

Newborn, 0-3M, 3-6M, 6-9M, 9-12M, 12-18M, 18-24M

As you can see, there is a lot of overlapping. This could cause confusion for a customer because it is difficult to pick just the right size range. Also, this doesn't reduce the number of sizes carried.

If we eliminate the newborn and preemie sizes and use the size range from JcPenney, we would get this:

0-3M, 6-9M, 12M, 18M, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16.

If you look carefully, you will see that I eliminated the 24M size and the T's on the 2, 3, and 4. This is where you have to decide how the size will appear on the care/content tag or hang tag. It would be best not to confuse customers - keep things simple and logical here.

You will also notice that there seems to be a size missing in the infant sizes. The size 6-9M is often combined because either the 6M or the 9M is considered a half size between the 3M and the 12M. This is obvious when you study measurement charts, so just take my word on it for now.

The other thing to consider when generating a size standard is the patternmaker/grader. The size 0-3M, for example can be created in one of two ways. The measurements of the Newborn and 3M could be averaged out or the patternmaker could just make the patterns a true 3M. In order to fit the most children, it is best to make the patterns fit the high-end of the range. In our example, the patterns would be made in a 3M. The clothing will fit loose on the small end of the range, but kids grow fast. The only exception might be sleepwear which needs to fit snug to the body in all of the size ranges. This is another place where you need to know your product and customer well.

By following this example, we have gone from a whopping 21 sizes to 15! While this still creates a lot of sizes, it is so much simpler and easier to understand.

0-3M, 6-9M, 12M, 18M, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16.

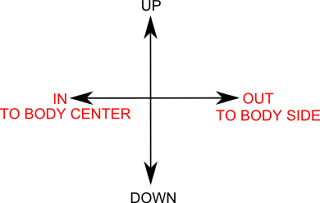

The next question to address is the grading question. And that will have to wait for tomorrow.