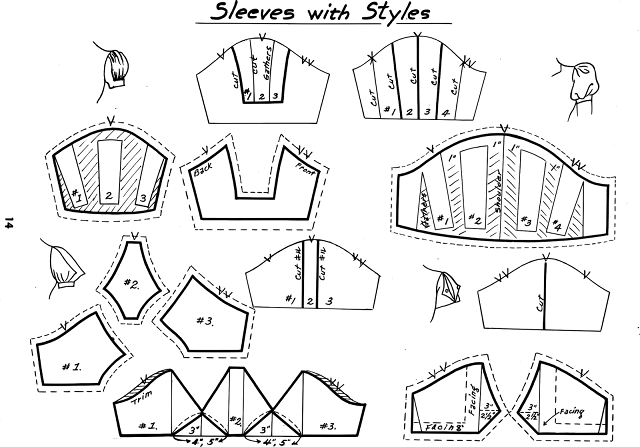

I've been hard at work on my grading book. The first half of the book explains children's sizing. The second half is a how-to manual on grading. I've been stuck on the how-to section for quite a while. I could not decide on whether I should do step-by-step photos or illustrations. I fiddled around in Inkscape and managed to pull together some pretty good how-to drawings. The drawing above is a sneak peak.

Photographs would be great but I didn't think I could pull off photographs that were good enough for print. There are some practical matters too. An eBook filled with as many photographs as I need would be enormous. Too big of a file size to process for print (fingers-crossed they turn out ok) and too big to download easily. There are photos in the book, but just a few. So yes, I am planning on an eBook version, though probably not for Kindle.

So the how-to section will be step-by-step drawings. The drawing above is the set-up for hand grading. It shows the guidelines and grading ruler placement. The shaded area represents tag board. The pattern piece is cut in tag board too, but is white for clarity.

The gridded area represents the grading ruler. My grading ruler is the rectangular gridded ruler in the middle below. I was lucky enough to find it at a thrift store stuck in the book below.

This style of hinged grading ruler is no longer available. Never fear, there are options. You can grade with any clear ruler that has 1/16" gradations like the 18 inch ruler in the picture above. You can also buy a grading ruler from Connie Crawford. The price can't be beat! I've been looking at special quilting rulers and those are tremendously over-priced in comparison.

The grading how-to section will cover hand grading in depth and a general overview of grading for CAD. CAD grading depends on the CAD software, so in depth instructions would be difficult to cover for each major system.

Because things can be lost in translation - meaning my drawings and photographs may not convey the best for everyone - there will be at least one how-to video. I'm not sure what I'm setting myself up for, but I'll give it a try.

November 03, 2014

October 13, 2014

What makes a second a second in apparel quality standards?

In the fashion industry a second is an item with a few defects that can still be worn or used. If there are seconds, then there are firsts though we don't call them that. We may call them first quality, though I rarely hear that term either. The word quality, all by itself, is a controversial term with various meanings attached to it. If there are firsts and seconds, then there are also thirds.

The goal of any company is to produce goods without any defects for the least amount of money possible. But as we all live in the real world, defects happen. I've worked for three different companies and how each handled defects were roughly the same. Each company came up with a ranking system to evaluate product during production and as it came off the line. Each ranking was called something a little different though they conveyed the same meaning. The qualification for each ranking varied and the product that fell into each ranking was handled differently. Here is a brief break down.

First - top quality goods with no obvious defects

Second - goods with X number of defects that may or may not be repaired, but still wearable or usable and can be sold on a secondary market.

Third - goods with sufficient number of serious defects to render the item unwearable or usable. These goods may be sold for scrap and may be called rejects.

Quality can be subjective and that can cause problems not only in production but in the retail sector. A first quality item can be rendered second or third after it's first wearing and washing. In that case, was the item truly a first quality item? Perhaps not. Likewise, a second can be repaired sufficiently to make it a first quality item. But is it financially feasible to repair a second to make it a first? These are all questions that individual companies must deal with as they develop and sell product. In order to not get too long-winded on this subject, let's look at something I recently purchased at the thrift store.

This is a cute knit top that I found at a thrift store for a few dollars. It looked pretty good when I tried it on in the dressing room, but as usual the lighting was bad and I missed some obvious problems. Once home I tried it on again and immediately saw a problem with the gathers on the neckband. I also noticed the brand label and content tag were off center. Also the elastic on one of the sleeve hems was pulling away. It is true that most thrift store clothes are previously worn and I have no doubt this shirt fit that category. But because of the defects, I think this shirt started life as a second and was likely sold at an outlet store or other secondary market.

A closer look reveals the problem on the neckline. There is some fabric caught in the seam. Unfortunately, I did not take any pictures of the problem from the other side, but the fabric caught in the stitching is more obvious.

This style of neckline would be difficult to sew, especially in a factory. First, each gathered area was pre-gathered by applying 1/4 inch clear elastic - stretched between notches. Next, the operator prepares the neck band. The tie and neckband are one piece. The tie portion is sewn and turned out and the rest of the neckband is folded in half. Hopefully there were notches to help the operator position the neck band on the neck, otherwise it would be easy to skew the neckband. Anyway, the operator matches up the neckband to the neckline, starting the sewing on the left side neck. The neckband would be on top and the neckline on bottom. The operator has to match the pre-gathered section from underneath to meet a match point on the band, catch enough of the seam under the foot securely and then stitch the pre-gathered section to the neckband. Hopefully there is another notch to indicate where the pre-gathered section should end. The sewing continues around the neck to the right side, where there is hopefully another notch to indicate where the next pre-gathered section should start. The neckline is then finished off, overedging the center front neck which is left unattached from the neckband. This small section is later topstitched down. Finally, the next operator would place the brand and size label to the back neck with a single needle machine within the seam allowance of the neckband/neckline.

The most difficult part of this whole sequence of steps would be where the operator starts attaching the neckband on the left side. The pre-gathered section is not stable and will move around as the pieces are placed under the foot. This is what happened here. Some additional fabric worked its way under the foot as the sewing began. The label placement would be difficult because the operator would have to guess where center back is and place the labels on a knit top that likes to move around.

This type of defect would have been difficult to repair in a factory. The elastic and two rows of stitching would be time consuming to undo and redo and look good. The poor placement of the brand labels would have been a second strike. The top was still wearable though and likely sold as a second or at a steep discount. I imagine there were quite a few seconds on this style....

Anyway, I was able to repair this top. I carefully unpicked the band with my fingers crossed that none of the shirt was cut when it was stitched. Luckily it wasn't. I removed some of the elastic in the affected area (it wasn't worth redoing the whole gathered area with the elastic), and regathered the neckline with a needle and thread. I then basted the neckband and neckline together to double check it was all right and stitched it back together. Almost as good as new - at least you can't tell there had ever been a problem.

The goal of any company is to produce goods without any defects for the least amount of money possible. But as we all live in the real world, defects happen. I've worked for three different companies and how each handled defects were roughly the same. Each company came up with a ranking system to evaluate product during production and as it came off the line. Each ranking was called something a little different though they conveyed the same meaning. The qualification for each ranking varied and the product that fell into each ranking was handled differently. Here is a brief break down.

First - top quality goods with no obvious defects

Second - goods with X number of defects that may or may not be repaired, but still wearable or usable and can be sold on a secondary market.

Third - goods with sufficient number of serious defects to render the item unwearable or usable. These goods may be sold for scrap and may be called rejects.

Quality can be subjective and that can cause problems not only in production but in the retail sector. A first quality item can be rendered second or third after it's first wearing and washing. In that case, was the item truly a first quality item? Perhaps not. Likewise, a second can be repaired sufficiently to make it a first quality item. But is it financially feasible to repair a second to make it a first? These are all questions that individual companies must deal with as they develop and sell product. In order to not get too long-winded on this subject, let's look at something I recently purchased at the thrift store.

This is a cute knit top that I found at a thrift store for a few dollars. It looked pretty good when I tried it on in the dressing room, but as usual the lighting was bad and I missed some obvious problems. Once home I tried it on again and immediately saw a problem with the gathers on the neckband. I also noticed the brand label and content tag were off center. Also the elastic on one of the sleeve hems was pulling away. It is true that most thrift store clothes are previously worn and I have no doubt this shirt fit that category. But because of the defects, I think this shirt started life as a second and was likely sold at an outlet store or other secondary market.

A closer look reveals the problem on the neckline. There is some fabric caught in the seam. Unfortunately, I did not take any pictures of the problem from the other side, but the fabric caught in the stitching is more obvious.

This style of neckline would be difficult to sew, especially in a factory. First, each gathered area was pre-gathered by applying 1/4 inch clear elastic - stretched between notches. Next, the operator prepares the neck band. The tie and neckband are one piece. The tie portion is sewn and turned out and the rest of the neckband is folded in half. Hopefully there were notches to help the operator position the neck band on the neck, otherwise it would be easy to skew the neckband. Anyway, the operator matches up the neckband to the neckline, starting the sewing on the left side neck. The neckband would be on top and the neckline on bottom. The operator has to match the pre-gathered section from underneath to meet a match point on the band, catch enough of the seam under the foot securely and then stitch the pre-gathered section to the neckband. Hopefully there is another notch to indicate where the pre-gathered section should end. The sewing continues around the neck to the right side, where there is hopefully another notch to indicate where the next pre-gathered section should start. The neckline is then finished off, overedging the center front neck which is left unattached from the neckband. This small section is later topstitched down. Finally, the next operator would place the brand and size label to the back neck with a single needle machine within the seam allowance of the neckband/neckline.

The most difficult part of this whole sequence of steps would be where the operator starts attaching the neckband on the left side. The pre-gathered section is not stable and will move around as the pieces are placed under the foot. This is what happened here. Some additional fabric worked its way under the foot as the sewing began. The label placement would be difficult because the operator would have to guess where center back is and place the labels on a knit top that likes to move around.

This type of defect would have been difficult to repair in a factory. The elastic and two rows of stitching would be time consuming to undo and redo and look good. The poor placement of the brand labels would have been a second strike. The top was still wearable though and likely sold as a second or at a steep discount. I imagine there were quite a few seconds on this style....

Anyway, I was able to repair this top. I carefully unpicked the band with my fingers crossed that none of the shirt was cut when it was stitched. Luckily it wasn't. I removed some of the elastic in the affected area (it wasn't worth redoing the whole gathered area with the elastic), and regathered the neckline with a needle and thread. I then basted the neckband and neckline together to double check it was all right and stitched it back together. Almost as good as new - at least you can't tell there had ever been a problem.

August 11, 2014

Knitting: Myrtle Cardigan pt. 6

I'm not sure if it is an error in the pattern or my interpretation. I just joined the sleeves by knitting across the row and following the lace pattern. At this point I think the pattern is telling me I should be on row 2 of the lace repeat where I start the armhole decreases. I'm on row 3. I did not know how to join the sleeves into the work without knitting across. This means I will work row 3 and begin sleeve decreases on row 4 (decreases are supposed to occur on the pattern rows). I don't think it will make much difference but the instructions left me a bit perplexed. I read through everything twice more and I followed everything right up until the join sleeves instruction.And then I had a head slapping moment. You CAN do decreases on the same row as joining sleeves to the body. So I ripped back - thank goodness for that lifeline that I put in just prior to adding the sleeves - and followed the instructions in the pattern on joining the sleeves. And then because it had been so long since I had worked on this, I worked the lace charts in the wrong order. I had to rip back again and start over.

I can safely say that I am on my way. I can also confirm that working only one repeat of the lace up the middle of the sleeves was also the right move. It makes doing the sleeve decreases so much easier. I have worked far enough that I have one extra repeat of the lace in the body. Now to do one more before decreasing for the neck. Fingers-crossed that I have enough yarn.

After working on this for over a year, I think I can see myself actually finishing this.

July 29, 2014

Experts and craftsmanship : who do you trust in the era of slick packaging and presentation?

The age of the Internet has fundamentally changed how we access information. It has changed the way we learn and share. In the sewing community we share projects, ideas, techniques. Some have even found ways to make money doing what they love.

There is a phrase I learned from someone, "You don't know what you don't know."

If you don't know what you don't know, how do you learn what you need to know? How do you even ask the right questions?

Perhaps I'm a bit thoughtful as I struggle to write my book on grading. How do I present a technical skill in an easy to understand, accessible way? The writing process is dragging on because I want to get the instructional information just right. In addition, I recently ran across a mommy blogger who is now teaching others how to grade patterns using patched together measurement charts* cribbed from various sources. I won't link to this particular person, but it gave me pause. Her past experience does not support her current endeavors, but she is perceived as an expert because of slick packaging and presentation. It's not that she can't gain skills and teach others, but where is the dividing line between what you don't know and where you know enough?

An expert is someone who has gained mastery, skills and experience of a particular subject. At what point does someone migrate from a beginner to an intermediate and then expert sewist or master pattern maker? I believe it is a journey of a lifetime. And for many, you only become an expert at one aspect because the overarching subject is too vast. In the industry you specialize, influenced by the first employment opportunity that guides your future.

More thoughts on this topic in the future....

*I've studied these charts and compared them to ASTM charts. Her charts contain proportion problems which may create fit issues.

June 16, 2014

Sleeve cap ease to fit around your shoulder is a myth

My most popular blog entry is Tutorial: Reduce/Remove Sleeve Cap Ease. Excessive ease in set-in sleeves continues to be a source of frustration for many. Still, there are those that continue to insist that sleeve cap ease is necessary in order for a sleeve to fit over the curve of your shoulder. Another well meaning sewist claimed my tutorial only worked for children's clothing (my specialty) because children are smaller, but adults definitely need ease.

Kathleen has written a now classic blog entry, Sleeve Cap Ease is Bogus (including a sequel). She even did a series on how to draft an armhole and sleeve correctly so that no ease is needed (partially gated). It would be worth your time to go back and reread those blog entries.

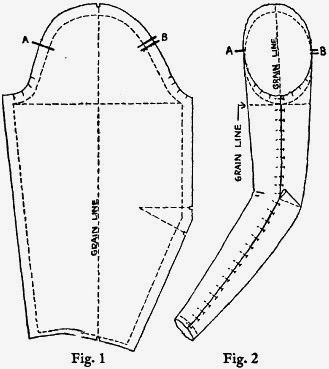

This idea that ease is needed for proper fit is interesting. Unfortunately, it is a false concept. A sleeve should not fit over the curve of a shoulder. Instead, the sleeve should hang straight down from the shoulder. The shoulder seam needs to extend long enough that it reaches to the widest part or tip of the shoulder. In the picture below you can see the shape of both the shoulder and armhole. This draft will allow the sleeve to hang from the shoulder.

Kathleen goes into greater detail about this in her blog entries. If you draft a sleeve as instructed by many pattern making manuals with the recommended 1-2 inches of ease, you will not be able to get beautiful looking sleeves like the ones found being worn by the actors of His Girl Friday. Notice the placement of the armhole seams.

Instead, you will get a sleeve that looks something like this:

|

| Photo courtesy of Kelly Hogaboom and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. |

Sleeve caps with ease amount to lazy pattern making, or at the very least pattern making without knowing better.

Children are really not much different when it comes to fit and pattern design. They do have fewer overall curves, so in many ways pattern making and fit are simpler. What curves they do have though, are smaller. Sewing a set-in sleeve in an infant sized bodice is in many ways more difficult. There is less length to work with and tighter curves. If ease is included it is just enough to allow the operator to get around that smaller circumference easier. The amount of ease is very small (1/4 to 1/2 inch) and is entirely dependent on the fabric. In many cases, it is not needed at all because the differential of a machine can be adjusted.

I can understand if this seems unbelievable. It certainly goes against the grain of conventional sewist wisdom. The best way to know, is to try it for yourself. Try using a pattern with sleeve cap ease and one without. Which sleeve is easier to sew in? Which looks better? At the end of the day, you choose which sleeve you prefer to work with.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)