As a fashion designer there is a way to transition your focus on the things you really want to accomplish. But changing your focus as a fashion designer can be challenging. Designers are attached to their brands and it can become a part of their identity. Letting things go so you can try something new is a bit scary. Though once the decision is made, you can take one step at a time to reach a happier place.

Evaluate your goals

If you have made the decision to transition, it is time to evaluate your goals. Goals can be super specific or more general. Do you want to own and produce your own brand? Do you have financial goals? Do you want to change product categories? It helps to write your goals and vision down. If you start more generally, you can drill down to specific steps. Smaller specific steps leading to your goal are more actionable.

Goals can change over time so it is perfectly fine to cross off or toss goals that are no longer a part of your vision. Goals do not have to be a rigid framework that do not allow for deviation. Life is not like that and changes in life require changes in your goals. As a designer, I have had to make changes in my professional goals as life has happened. This is normal, so allow flexibility in your decision making and goal setting.

Choosing a new focus area

Fashion designers can design many product categories from shoes and accessories to all types of clothing. Usually a designer specializes in one product category and becomes known for one type of work. This can make a designer feel trapped because they feel like they can only design one thing. Large design houses will design and produce an entire look from head to toe. Smaller design entrepreneurs are not financially able to do the same thing and so they produce they same type of product from one season to the next.

If you own your own business, look at adding a new, but related, product category. For example, a children's clothing designer that creates sleepwear could explore playwear or bedding. Adding that new product category can reinvigorate your motivation and provide a challenge that holds your attention.

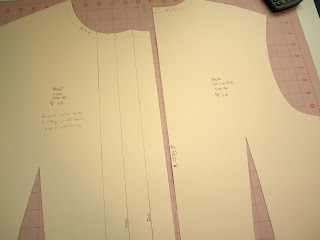

As an employee, you could begin working on your own design ideas on the side. Begin to turn your ideas and dreams into an actual product. Draft the patterns and sew up a sample. Work on it until you are satisfied.

Evaluate and sharpen your skills

Regardless of your current position, you can begin to explore related career tracks in the fashion industry. Begin by listing all of your skills. Today's fashion designer has skills in many areas. Here are just a few ideas:

- Graphic design

- Artist drawing or painting

- Social media marketing

- Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop

- Sewing

- Patternmaking

- Spreadsheets

- Training/Coaching

- Sourcing/Outsourcing

- Product development

Each of the above skills can be used in other employment or freelance. Perhaps you no longer want to create and sell a product or run a business. You could start a consulting business for other designers helping them develop their product. Perhaps you love sourcing materials. You could help other designers find the right fabrics and trims. Or perhaps you love to draw. You could provide freelance drawing services to other designers who can not draw (you would be surprised at how many can't draw). I have a friend that creates drawings of client's wedding dresses as a keepsake.

Perhaps there is an area that you want to improve. Now is the time to sharpen those skills. Take an online class in search engine optimization or social media marketing. Improve your drawing skills by starting a daily drawing practice. Create a portfolio of your work. Create an outline for a training class.

Hire Help

Many fashion designers also run their own companies, bootstrapping as they go. Eventually you reach a point where you need help. The stresses of running a business while also being the creative leader can be overwhelming. At the same time, hiring an employee costs money. If you can't hire an employee to work with you at your office or design studio, look at hiring a virtual assistant. Either way you can outsource or delegate the tasks that you dread doing. If you need or want time to focus on the more creative aspects of your business, then get someone else to handle the more mundane tasks. There are plenty of people that can make phone calls and research sourcing options. A virtual assistant can lessen the financial impact of a regular assistant and still accomplish the small tasks you may not want to deal with on a daily basis.

If you are an employee looking to transition, and have the means to do so, you can still hire an assistant. A virtual assistant can take care of the tasks you can't accomplish during the day when you are at work and help you move things along.

Transitioning your focus to something new

Sometimes it is necessary to make drastic changes. This may mean shutting down a business, switching career tracks, finding new employment, or maybe even starting a new business. If you are in this situation, there are things you can do to help ease the transition.

Before making the leap to something else, have an emergency fund. Prepare financially by building your cash reserves so you can still eat and pay rent. Having to worry about daily living essentials can cause you to abandon your dream and force you to take the next available opportunity even if it does not match your goals. If you are transitioning to freelance work, a fund will greatly improve your chances of success.

Try to have a plan in place with actionable steps. If you quit what you are doing now with no plan, it will take you even longer to transition. Let's say you want to become a coach to other designers. Here is what your plan may look like:

- Start an educational blog

- Collect email addresses of possible clients

- Email potential clients introducing yourself

- Create a proposal and determine rates

I've spent the last year or so on my own transition. I've worked as a patternmaker, technical designer and designer for over 20 years specializing in children's special occasion clothing. There are many things I enjoyed about my work. I loved working with expensive fabrics and trims to create something beautiful for a special event that would be kept as an heirloom or memory. Still, I made basically the same product over and over again with minor variation. Creatively, I became bored. At the same time I was battling chronic fatigue and I was being forced to evaluate my current work load. Since then I have evaluated my skills and found a new related focus that has me energized and is bringing me back to the business one step at a time.