Like many, I have had my ups and downs with keeping a journal or planner. The New Year starts off with a lot of motivation which runs out in a few months. I have purchased or been given planners with pretty pre-printed calendars and spreads and I have gone months without using it. Sometimes those journals are hard to use because the pre-printed spreads do not fit my productivity style or they are to rigid in their approach. Other times the planners are too big and bulky to carry with me despite how beautiful they are designed. The Bullet Journal has been the method or style I have stuck with the longest. I have been bullet journaling for four years, which is a record. There are several things I like about this method.

Customization

You can do whatever you want with your bullet journal. If you browse Youtube, there are a lot of artists and people in the planner community who like to make pretty planners. They spend a lot of time illustrating and drawing out their planners. They love certain pens, pens with special ink and, of course, stickers. You can do this if you want but it does take a lot of time.

I am a bullet journal purist. I create lists and check things off. There is absolutely no need to decorate or illustrate your pages unless you want to do it. You can use any type of journal -- lined, dot, or grid. Discount stores, including Walmart, carry these types of journals and you can get started at a very low cost.

A catch-all place

I really like the idea of my bullet journal being a catch-all. I really dislike posting sticky notes on my desk and around my computer monitor. It's messy and cluttered. I also get sticky note blindness. I just don't see them because I focus on the task that is top of mind. So notes, reminders, phone numbers to add to my contacts list, all get added to the journal to deal with later.

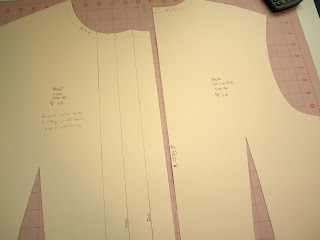

I use my bullet journal for project planning. I create an outline of the idea with individual tasks for each step. As a task is completed, I flip back to the project page and check off each task. Sometimes the project idea tasks migrate across my daily to-do's, but I always have that original reference. This type of project planning is perfect for designers as they start a new season.

I use my bullet journal for note taking during meetings and conferences. No need to bring a separate notebook, it all goes in one place. Later, as I review my notes I can create new tasks based on areas of inspiration or goal setting. I attended a conference back in October and several work-related tasks evolved from my notes. It also helped reinforce ideas that I thought were important.

Bullet journaling as a Fashion Designer

You can use one bullet journal for both personal and work related tasks. It is easier to keep track of one journal versus two, but it would be easy to overwhelm your personal tasks with design work tasks. Designing a collection comes with making hundreds of decisions with dozens of things to keep track of at the same time.

If you are a freelancer or employee, I do recommend

keeping a work journal. It's important to keep track of client work and what is accomplished so you can determine your billable hours. It also adds a layer of protection so you can prove what you did. You can keep this journal in the style of a bullet journal or however you choose.

If you own a fashion business, a bullet journal can absolutely help keep you on track to meet deadlines. A work journal that is separate from a personal journal will help keep the two things separate so that neither space is overwhelmed. I keep my work journal at work so I am unable to look at it home. This sets a healthy boundary so that I truly get a break. I do carry my personal bullet journal with me most places so that anything truly important can be recorded. For truly in the middle of the night work or design ideas, I send a simple email to myself that I will read in the morning.

Either way, you can figure out a method that works best for you. One or two journals, personal and/or work related. The system is flexible enough to experiment until you find the method that is the most useful.

Productivity hacks

A bullet journal is definitely an analog approach to planning and organizing. This method helps me to mentally retain my tasks and ideas for far longer by physically writing them down. It gives me mental space and breathing room by brain dumping tasks and ideas onto paper so that the stress of having to remember it is removed

A bullet journal can be combined with digital calendaring, reminders, and contact lists. The method is flexible enough that you do not have to feel like you are doing double work. If you like to setup a calendar with reminders, then you can certainly do it. Planning out on paper first can help with laying things out digitally. You can use productivity tools like Asana or Monday.com and still use a bullet journal. As project tasks were assigned to me in Asana, they were transferred to my bullet journal. A journal seemed easier to refer back to whereas the digital tools were helpful for future reminders. Either way, you can incorporate both ideas or methods.

The productivity hack that I have recently implemented is to create your to-do lists at the end of the day in preparation for the next day. I always had this vision that I would wake up early and have time to myself to plan my day and do a bit of reading. With my chronic fatigue and busy days, it never happened. I could never remember from one day to the next what tasks needed to be done. So now I spend maybe 15 minutes in the evening reviewing my tasks and creating tomorrow's to-do list. The next morning a simple review of my to-do list gets me started in the right direction.

If you are interested in learning more about bullet journaling, you can read about the

Bullet Journal Method by Ryder Carroll. There are also lots of

journals available on Amazon including

fineliner pens.