This video gives some sneak peaks about what is in the book! Available for purchase at Amazon and MelanderDesigns.com.

Showing posts with label Grading. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Grading. Show all posts

August 20, 2022

July 20, 2022

The Essential Guide to Children's Clothing Sizes and How to Grade Them

I am excited to announce my new book, The Essential Guide to Children's Clothing Sizes and How to Grade Them. This book explains children's clothing sizes in the United States, how they came about, and what sizes are used today. This book includes many things that have never been included in books on children's clothing design in the past.

- A break down and explanation of children's clothing sizes from Preemie to size 16, including boys sizes.

- A brief overview of difficulties in the industry, including obesity, and sleepwear

- An explanation of how create your own grade rules.

- Step-by-step instructions on how to grade basic styles, including grade rule charts.

- Body measurement charts for infants to size 14, including slim and plus sizes for older children.

- The infant measurement chart includes head circumference, neck circumference, hand length and width, foot length and width -- measurements that are hard to find.

- Extra grade rule charts that include Newborn and size 9 months.

- CAD grade rule charts

- Complete measurement studies with additional body measurements, grade rules and references for infants, toddlers, 4-6x, girls (7-14), boys, and young men.

October 29, 2018

Understanding pattern grading for children's clothing

I'm catching up with some questions and comments. It's been a while since I've answered a grading question.

Men's clothing has many more sizes. These sizes are given size names that correspond to actual body measurements such as waist, pant leg inseam, or neck and sleeve. The circumference difference is usually 1 inch but it may be 2 inches for larger sizes.

Children's clothing is different. Children grow exponentially from birth. Their growth makes it difficult to group children into size groups, but over 70 years ago a measurement study managed to give us enough measurement data to do just that. That measurement data shows that the change between children's sizes is not even. This is true regardless of how sizes are arranged or named. The circumference measurement difference may range between 1/2" to 1" or more. There are similar irregularities in length grades. Children's clothing brands interpret measurements in their own way, so you will see variation in the marketplace.

Speaking to this particular question. If you group your children's sizes so they are called 0-3M, 3-6M, 6-9M, etc., your grade rule will still vary between the sizes. But there will be no grade change between a 3M and a 6M in the size called 3-6M. When developing a grade rule for this kind of size system, I interpret the sizes like this:

0-3M = 3M

3-6M = 6M

6-9M = 9M

You can call your sizes whatever you choose, but for pattern making and grading you have to assign a meaning to that size. Interpreting sizes with a size label of 0-3M as a single size 3M is the easiest way to develop grade rules and it seems to work.

My brain is spinning with all the reading I've been doing on this subject. Can you please explain to me why I couldn't grade within my separate size ranges by grading, for example, 3-6 with one particular grade rule and then taking then changing my grade rule for the next section? Would this not be taking the difference growth rates and such into account? I feel like there's probably a reason that I haven't quite grasped yet. Thanks so much.Grading women's clothing is different from grading children's clothing. Women's clothing is graded with either a 1 1/2" or 2" grade between the sizes. This grade rule refers to the change in circumference measurements between the sizes. There is a lot of criticism for this grade rule because it appears to not have a connection to actual body measurements. That assumption is not strictly true, but it is true this practice is a convenience for the industry. It is too difficult to mass produce clothing and create a custom fit for an individual woman. This grading convention has historically proven to fit the most women in the most efficient way.

Men's clothing has many more sizes. These sizes are given size names that correspond to actual body measurements such as waist, pant leg inseam, or neck and sleeve. The circumference difference is usually 1 inch but it may be 2 inches for larger sizes.

Children's clothing is different. Children grow exponentially from birth. Their growth makes it difficult to group children into size groups, but over 70 years ago a measurement study managed to give us enough measurement data to do just that. That measurement data shows that the change between children's sizes is not even. This is true regardless of how sizes are arranged or named. The circumference measurement difference may range between 1/2" to 1" or more. There are similar irregularities in length grades. Children's clothing brands interpret measurements in their own way, so you will see variation in the marketplace.

Speaking to this particular question. If you group your children's sizes so they are called 0-3M, 3-6M, 6-9M, etc., your grade rule will still vary between the sizes. But there will be no grade change between a 3M and a 6M in the size called 3-6M. When developing a grade rule for this kind of size system, I interpret the sizes like this:

0-3M = 3M

3-6M = 6M

6-9M = 9M

You can call your sizes whatever you choose, but for pattern making and grading you have to assign a meaning to that size. Interpreting sizes with a size label of 0-3M as a single size 3M is the easiest way to develop grade rules and it seems to work.

May 26, 2015

Grading from body measurements pt. 3

This is part three of an ongoing discussion about N. A. Schofield's

article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. Part one

is here, part two here. I recommend reading the previous parts of this series before reading this one.

So what were the results of Schofield's experiment? I can't reproduce the actual results here, but it was something like this.

Imagine the square is a bodice pattern piece in one size. The star is supposed to be the same pattern piece but graded to the next size. Clearly, the two shapes have no proportional relationship to each other. The problem is further compounded by a different grade for corresponding pieces.

Imagine these are front and back bodice pattern pieces. Each corresponding pattern piece was graded separately based on the measurement data for that body location. Now imagine trying to sew the front and back together. It can't be done. Schofield freely admits the difficulty in the results. Though she also believes we need to learn how to deal with new shapes in pattern pieces in order to achieve superior fit.

Schofield's experiment left me with a lot of questions. I did not understand completely why she rejected the ASTM measurement data, nor why she went back to essentially raw data. Her grading methodology left me a bit confused. The results were clearly not suitable for industry application. Superior fit is the holy grail of fashion, but I'm not convinced that grading is the entire source of the problem. Superior fit, for each individual might only be achieved on an individual basis. In this case, 3D body scanning and customized clothing is the answer, but is it practical?

I would like to see this experiment repeated. The factors that will impact additional experiments are the measurement data and grading methodology. Why not use ASTM measurement data? Why not use traditional grading methods? I always support those who are willing to test ideas and theories. This was a worthy attempt by Schofield to ask important why and how questions.

So what were the results of Schofield's experiment? I can't reproduce the actual results here, but it was something like this.

Imagine the square is a bodice pattern piece in one size. The star is supposed to be the same pattern piece but graded to the next size. Clearly, the two shapes have no proportional relationship to each other. The problem is further compounded by a different grade for corresponding pieces.

Imagine these are front and back bodice pattern pieces. Each corresponding pattern piece was graded separately based on the measurement data for that body location. Now imagine trying to sew the front and back together. It can't be done. Schofield freely admits the difficulty in the results. Though she also believes we need to learn how to deal with new shapes in pattern pieces in order to achieve superior fit.

Schofield's experiment left me with a lot of questions. I did not understand completely why she rejected the ASTM measurement data, nor why she went back to essentially raw data. Her grading methodology left me a bit confused. The results were clearly not suitable for industry application. Superior fit is the holy grail of fashion, but I'm not convinced that grading is the entire source of the problem. Superior fit, for each individual might only be achieved on an individual basis. In this case, 3D body scanning and customized clothing is the answer, but is it practical?

I would like to see this experiment repeated. The factors that will impact additional experiments are the measurement data and grading methodology. Why not use ASTM measurement data? Why not use traditional grading methods? I always support those who are willing to test ideas and theories. This was a worthy attempt by Schofield to ask important why and how questions.

April 16, 2015

Grading from body measurements pt. 2

This is part two of an ongoing discussion about N. A. Schofield's article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. Part one is here.

My initial reaction to the idea of grading from body measurements was, "Well, of course we should." And in fact, we do for children's clothing. It seemed rather obvious to me to look at children's clothing as a model. Children's sizing is based on the idea of growth, meaning that the measurement intervals between sizes are not always consistent.

Let's look at an example for a 4-6x size range.*

For sizes 4, 5, 6, 6x

Chest: 23, 24, 25, 25.5

Waist: 21.5, 22, 22.5, 23

Hip: 23.5, 24.5, 25.5, 26.5

The grade works out to be, choosing size 5 as the base size:

Chest: 1, 0, 1, 1.5

Waist: 0.5, 0, 0.5, 0.5

Hip: 1, 0, 1, 1

In this example, we have a 1" chest grade, except for size 6x which is 1.5". The waist is a 0.5" inch grade and the hip returns to a 1" grade for all sizes. Each body measurement area has it's own grade.

In women's clothing a 2" grade means that the interval change between the sizes will be 2" for chest, waist, and hips. Though even this isn't true across all brands, and you will find variations. (IMO, this is a good thing)

I don't know the history of women's sizing well enough to explain how this mode of practice came to be nor exactly why. It is clear that it does make grading, especially hand grading, much easier in practice. It is also unclear to me that grading is the source of our fitting woes. Nevertheless, it does make sense to me to go back and look at body measurements and devise a more precise grade rule.

The question then becomes, which body measurements do we use? In my children's example above, the numbers are still nice and easy to work with. The body measurements have been intentionally manipulated to be easy to work with. Raw measurement data was averaged, sorted, and studied to arrive at some numbers. Those numbers were not easy to work with, so a group of industry professionals sat down and made them that way. They modified certain measurements by about 1/8" to achieve consistency. Their modifications were rather minor and easily fall within a statistical margin of error. If you read their reasoning, it makes sense. This manipulation of measurement data for ease of use continues today in more modern measurement studies. It seems deceitful, but at the end of the day is infinitely practical. ASTM D4910 inherits this method of data handling from the measurement studies done in the 1940s, but does provide some updated measurements.

Looking at the Misses body measurement chart, ASTM D5585, it seems to be arranged and handled in the same way as the children's body measurement chart. IOW, the chart does not show a 1, 1.5, or 2 inch grade in the body measurements. It is a lot like the children's example above. There does seem to be a disconnect between measurement data and grading, at least on the surface. Individual companies will decide how to interpret and implement measurement data, and therefore their grade rules. (IMO, I think this is a good thing). And some will use a 2 inch grade, and some will not.

So what measurement data did Schofield use? She rejected the ASTM charts and created her own version of measurements derived from body measurement studies. This presented a problem because measurement studies do not always include the measurements needed for pattern making and grading. Schofield did not normalize the data, in other words make it easy to work with. Also she had to figure out how to deal with missing measurement data. I no longer have a copy of the article and can't look back, but Schofield selected certain measurements over others. How and why she handled those measurements puzzled me.

I believe Schofield's goal was to remove the idea of maintaining an ideal proportion or predictable pattern shape. She wanted to see what the body measurements really did between sizes.

Her results were almost predictable. More on that later.

*These measurements come from the withdrawn child measurement standard CS151-50. Measurements are in inches.

My initial reaction to the idea of grading from body measurements was, "Well, of course we should." And in fact, we do for children's clothing. It seemed rather obvious to me to look at children's clothing as a model. Children's sizing is based on the idea of growth, meaning that the measurement intervals between sizes are not always consistent.

Let's look at an example for a 4-6x size range.*

For sizes 4, 5, 6, 6x

Chest: 23, 24, 25, 25.5

Waist: 21.5, 22, 22.5, 23

Hip: 23.5, 24.5, 25.5, 26.5

The grade works out to be, choosing size 5 as the base size:

Chest: 1, 0, 1, 1.5

Waist: 0.5, 0, 0.5, 0.5

Hip: 1, 0, 1, 1

In this example, we have a 1" chest grade, except for size 6x which is 1.5". The waist is a 0.5" inch grade and the hip returns to a 1" grade for all sizes. Each body measurement area has it's own grade.

In women's clothing a 2" grade means that the interval change between the sizes will be 2" for chest, waist, and hips. Though even this isn't true across all brands, and you will find variations. (IMO, this is a good thing)

I don't know the history of women's sizing well enough to explain how this mode of practice came to be nor exactly why. It is clear that it does make grading, especially hand grading, much easier in practice. It is also unclear to me that grading is the source of our fitting woes. Nevertheless, it does make sense to me to go back and look at body measurements and devise a more precise grade rule.

The question then becomes, which body measurements do we use? In my children's example above, the numbers are still nice and easy to work with. The body measurements have been intentionally manipulated to be easy to work with. Raw measurement data was averaged, sorted, and studied to arrive at some numbers. Those numbers were not easy to work with, so a group of industry professionals sat down and made them that way. They modified certain measurements by about 1/8" to achieve consistency. Their modifications were rather minor and easily fall within a statistical margin of error. If you read their reasoning, it makes sense. This manipulation of measurement data for ease of use continues today in more modern measurement studies. It seems deceitful, but at the end of the day is infinitely practical. ASTM D4910 inherits this method of data handling from the measurement studies done in the 1940s, but does provide some updated measurements.

Looking at the Misses body measurement chart, ASTM D5585, it seems to be arranged and handled in the same way as the children's body measurement chart. IOW, the chart does not show a 1, 1.5, or 2 inch grade in the body measurements. It is a lot like the children's example above. There does seem to be a disconnect between measurement data and grading, at least on the surface. Individual companies will decide how to interpret and implement measurement data, and therefore their grade rules. (IMO, I think this is a good thing). And some will use a 2 inch grade, and some will not.

So what measurement data did Schofield use? She rejected the ASTM charts and created her own version of measurements derived from body measurement studies. This presented a problem because measurement studies do not always include the measurements needed for pattern making and grading. Schofield did not normalize the data, in other words make it easy to work with. Also she had to figure out how to deal with missing measurement data. I no longer have a copy of the article and can't look back, but Schofield selected certain measurements over others. How and why she handled those measurements puzzled me.

I believe Schofield's goal was to remove the idea of maintaining an ideal proportion or predictable pattern shape. She wanted to see what the body measurements really did between sizes.

Her results were almost predictable. More on that later.

*These measurements come from the withdrawn child measurement standard CS151-50. Measurements are in inches.

April 09, 2015

Grading from body measurements pt. 1

Pattern grading is the process by which new sizes are developed from an existing pattern. There are various methods or processes used to grade a pattern. These methods include slash-and-spread, shifting, and CAD. At the end of the day, each method accomplishes the same thing, a new size.

The apparel industry has received a lot of criticism for their sizing, especially of women's clothing. At it's core, sizing goes hand-in-hand with pattern grading. You have to define your sizes in order to grade a pattern. In order to grade a pattern you have to know body measurements for each size. The common grade rules for women's apparel is the 1", 1.5" and 2" grade rules used in the United States. Similar grade rules are found in Europe and the UK. The primary criticism is that these grade rules are not based on anthropometric data, or actual body measurements. Instead these grade rules are just pulled out of a hat without regard to women or their fitting needs. These arbitrary grade rules are merely for the convenience of industry.

This is the point of view taken by N. A. Schofield in her article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. The goal of her research was to test the idea of creating grade rules based on actual body measurements rather than an arbitrary grade rule. There has been a lot of criticism of the industry over sizing and it is a worthy goal to research alternatives. Asking the why questions. Why does the apparel industry do things the way they do? Why do we grade women's clothing this way? Can we do it differently? I've asked a lot of these same questions as I've looked at children's clothing. When I started out, I didn't understand the why and sometimes the answer was not satisfying. I can totally get behind Schofield's motivation to try and find an answer.

And yet, I feel like I am setting up to be very critical of Schofield's research and I don't want to give the impression, as an industry professional, that even asking the questions were wrong. She was right to ask the question and to test an alternative. The results of her research are interesting and ironically (and indirectly) add support to current practices.

So here are some of Schofield's main arguments:

1. 1", 1.5", and 2" grade rules are not based on anthropometric data. Meaning it is not based on body measurements or the proportional relationships between body parts/areas. These grade rules were intended for the convenience and ease of hand grading.

2. Grade rules should be derived from body measurements. This means that grade breaks between bust, waist, and hips should not be consistent. Instead of a 34-36-38 chest measurement, we should be seeing a 34-35.5-38 (just as an example), chest measurement.

3. Size prediction and also body measurement prediction needs refinement. This idea is rather complex. Body measurement studies create a lot of raw data. In order to make sense of it, statisticians will test size prediction by using one or two body measurements. So can you predict the overall body size by using just the height or chest measurement? And if you do that, what influence does that have on other body measurements? If a person gets taller, do they also get wider? It is a complex question and not easily answered because there are so many variables. Statisticians bring order to raw measurement data so that we can organize the body measurements into sizes. They do this by averaging and, in some cases, normalizing the data so we can work with it easily. Schofield implies that we should just rely on the raw measurement data.

The ultimate goal of this study was to improve overall fit of women's apparel by basing grade rules on actual body measurements. I'll have to break up my review of this study into multiple blog entries because I have a lot to say about it. So stay tuned.

The apparel industry has received a lot of criticism for their sizing, especially of women's clothing. At it's core, sizing goes hand-in-hand with pattern grading. You have to define your sizes in order to grade a pattern. In order to grade a pattern you have to know body measurements for each size. The common grade rules for women's apparel is the 1", 1.5" and 2" grade rules used in the United States. Similar grade rules are found in Europe and the UK. The primary criticism is that these grade rules are not based on anthropometric data, or actual body measurements. Instead these grade rules are just pulled out of a hat without regard to women or their fitting needs. These arbitrary grade rules are merely for the convenience of industry.

This is the point of view taken by N. A. Schofield in her article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. The goal of her research was to test the idea of creating grade rules based on actual body measurements rather than an arbitrary grade rule. There has been a lot of criticism of the industry over sizing and it is a worthy goal to research alternatives. Asking the why questions. Why does the apparel industry do things the way they do? Why do we grade women's clothing this way? Can we do it differently? I've asked a lot of these same questions as I've looked at children's clothing. When I started out, I didn't understand the why and sometimes the answer was not satisfying. I can totally get behind Schofield's motivation to try and find an answer.

And yet, I feel like I am setting up to be very critical of Schofield's research and I don't want to give the impression, as an industry professional, that even asking the questions were wrong. She was right to ask the question and to test an alternative. The results of her research are interesting and ironically (and indirectly) add support to current practices.

So here are some of Schofield's main arguments:

1. 1", 1.5", and 2" grade rules are not based on anthropometric data. Meaning it is not based on body measurements or the proportional relationships between body parts/areas. These grade rules were intended for the convenience and ease of hand grading.

2. Grade rules should be derived from body measurements. This means that grade breaks between bust, waist, and hips should not be consistent. Instead of a 34-36-38 chest measurement, we should be seeing a 34-35.5-38 (just as an example), chest measurement.

3. Size prediction and also body measurement prediction needs refinement. This idea is rather complex. Body measurement studies create a lot of raw data. In order to make sense of it, statisticians will test size prediction by using one or two body measurements. So can you predict the overall body size by using just the height or chest measurement? And if you do that, what influence does that have on other body measurements? If a person gets taller, do they also get wider? It is a complex question and not easily answered because there are so many variables. Statisticians bring order to raw measurement data so that we can organize the body measurements into sizes. They do this by averaging and, in some cases, normalizing the data so we can work with it easily. Schofield implies that we should just rely on the raw measurement data.

The ultimate goal of this study was to improve overall fit of women's apparel by basing grade rules on actual body measurements. I'll have to break up my review of this study into multiple blog entries because I have a lot to say about it. So stay tuned.

January 06, 2015

Book review : Sizing in clothing

This is one of the books I ran across while working on my own book on grading. Sizing in Clothing (Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles)

The audience for this book is very narrow in scope. This is not a book for someone starting their own apparel line. Do not run out and buy this book unless you have a real interest in sizing theory - it will not help you figure out the sizing for your line. If you did want to buy it, the book runs in the $200-$250 range. I obtained a copy through inter-library loan, which also proved a bit of a challenge. Only a handful of college libraries carry a copy they are willing to loan outside their library system. So I had to read this book on a deadline and handle the book with kid gloves over the holidays.

Some technical designers, pattern makers, and graders may be interested in some of the included articles. Over the next several weeks, I will post a review/discussion on some of the topics covered. My two favorite articles were on the History of sizing systems and ready-to-wear garments by Winifred Aldrich and Military Sizing. There are other really great topics about sizing and target markets, size standardization (a hot topic!), apparel production and sizing, and of course, pattern grading.

Because each chapter is written by different authors, it's hard to give a review of the book as a whole. Some articles were very well written and easy to read, such as my two favorites listed above. Others are written in a formal academic style which is very difficult to read and even more difficult to ferret out what the author is trying to say. As a collection, the articles cover nearly every angle.

Since the articles are written mostly by academics, there is a bit of a disconnect with those working on the front lines (the exception being the Military sizing article). It would be easy to characterize the writers as sitting in their academic ivory towers telling us what to do because they "know better". Embedded in many of the articles is criticism aimed at the industry for assumed sizing problems that the industry either "created" or refuse to solve. While some of the criticism is unfair in my opinion, the information they provide us is still valuable. I'll discuss some of this later in the individual reviews. Despite all of this, I'm glad there are people out there willing to think about these problems, propose solutions, and test them out.

November 03, 2014

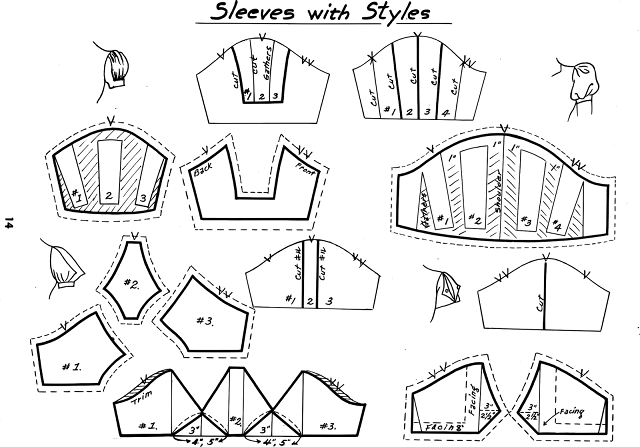

Grading rulers and how-to drawings

I've been hard at work on my grading book. The first half of the book explains children's sizing. The second half is a how-to manual on grading. I've been stuck on the how-to section for quite a while. I could not decide on whether I should do step-by-step photos or illustrations. I fiddled around in Inkscape and managed to pull together some pretty good how-to drawings. The drawing above is a sneak peak.

Photographs would be great but I didn't think I could pull off photographs that were good enough for print. There are some practical matters too. An eBook filled with as many photographs as I need would be enormous. Too big of a file size to process for print (fingers-crossed they turn out ok) and too big to download easily. There are photos in the book, but just a few. So yes, I am planning on an eBook version, though probably not for Kindle.

So the how-to section will be step-by-step drawings. The drawing above is the set-up for hand grading. It shows the guidelines and grading ruler placement. The shaded area represents tag board. The pattern piece is cut in tag board too, but is white for clarity.

The gridded area represents the grading ruler. My grading ruler is the rectangular gridded ruler in the middle below. I was lucky enough to find it at a thrift store stuck in the book below.

This style of hinged grading ruler is no longer available. Never fear, there are options. You can grade with any clear ruler that has 1/16" gradations like the 18 inch ruler in the picture above. You can also buy a grading ruler from Connie Crawford. The price can't be beat! I've been looking at special quilting rulers and those are tremendously over-priced in comparison.

The grading how-to section will cover hand grading in depth and a general overview of grading for CAD. CAD grading depends on the CAD software, so in depth instructions would be difficult to cover for each major system.

Because things can be lost in translation - meaning my drawings and photographs may not convey the best for everyone - there will be at least one how-to video. I'm not sure what I'm setting myself up for, but I'll give it a try.

Photographs would be great but I didn't think I could pull off photographs that were good enough for print. There are some practical matters too. An eBook filled with as many photographs as I need would be enormous. Too big of a file size to process for print (fingers-crossed they turn out ok) and too big to download easily. There are photos in the book, but just a few. So yes, I am planning on an eBook version, though probably not for Kindle.

So the how-to section will be step-by-step drawings. The drawing above is the set-up for hand grading. It shows the guidelines and grading ruler placement. The shaded area represents tag board. The pattern piece is cut in tag board too, but is white for clarity.

The gridded area represents the grading ruler. My grading ruler is the rectangular gridded ruler in the middle below. I was lucky enough to find it at a thrift store stuck in the book below.

This style of hinged grading ruler is no longer available. Never fear, there are options. You can grade with any clear ruler that has 1/16" gradations like the 18 inch ruler in the picture above. You can also buy a grading ruler from Connie Crawford. The price can't be beat! I've been looking at special quilting rulers and those are tremendously over-priced in comparison.

The grading how-to section will cover hand grading in depth and a general overview of grading for CAD. CAD grading depends on the CAD software, so in depth instructions would be difficult to cover for each major system.

Because things can be lost in translation - meaning my drawings and photographs may not convey the best for everyone - there will be at least one how-to video. I'm not sure what I'm setting myself up for, but I'll give it a try.

July 29, 2014

Experts and craftsmanship : who do you trust in the era of slick packaging and presentation?

The age of the Internet has fundamentally changed how we access information. It has changed the way we learn and share. In the sewing community we share projects, ideas, techniques. Some have even found ways to make money doing what they love.

There is a phrase I learned from someone, "You don't know what you don't know."

If you don't know what you don't know, how do you learn what you need to know? How do you even ask the right questions?

Perhaps I'm a bit thoughtful as I struggle to write my book on grading. How do I present a technical skill in an easy to understand, accessible way? The writing process is dragging on because I want to get the instructional information just right. In addition, I recently ran across a mommy blogger who is now teaching others how to grade patterns using patched together measurement charts* cribbed from various sources. I won't link to this particular person, but it gave me pause. Her past experience does not support her current endeavors, but she is perceived as an expert because of slick packaging and presentation. It's not that she can't gain skills and teach others, but where is the dividing line between what you don't know and where you know enough?

An expert is someone who has gained mastery, skills and experience of a particular subject. At what point does someone migrate from a beginner to an intermediate and then expert sewist or master pattern maker? I believe it is a journey of a lifetime. And for many, you only become an expert at one aspect because the overarching subject is too vast. In the industry you specialize, influenced by the first employment opportunity that guides your future.

More thoughts on this topic in the future....

*I've studied these charts and compared them to ASTM charts. Her charts contain proportion problems which may create fit issues.

April 29, 2014

Grading vocabulary - Nest and stack point

As I have attempted to learn how to code (computer programming), I have been stymied by one simple problem. Vocabulary. Most programming manuals or tutorials assume the learner has some basic knowledge about programming and skip explaining essential skills or words. This is even true of the manuals designed for complete idiots and absolute beginners. One good example in the programming world is the word compiler. I understand it on a basic level as a set of instructions that tells the computer how to link various files to create the executable software program.* There are various ways to deal with compilers depending on the programming language and platform used. I didn't know what compilers there were, which to use, how to write the instructions, etc. All I could find was some pretty lousy examples that I could copy and paste and they magically (or not) worked. I could present dozens of examples of this disconnect as I've stumbled my way through working on SodaCAD.

Grading manuals are similar, at least the ones I have used. They lack sufficient or clear explanations of the most basic of terms. Often times the manual writers skip sizing theory and jump to demonstrating their preferred grading method. This includes the much revered Jack Handford grading manual, the manual I still use and recommend today. Handford's book was the first that helped me understand grading but I recently reviewed the book and noticed the notations I made where I was confused.

One of my goals in writing my grading manual is to include a Grading 101 section. The above drawing is the illustration for two terms.

Nest - pattern pieces within a size range that are stacked along a common point or line. Indicated here by the horizontal line and star.

Stack point - the point at which pattern pieces are aligned, generally located in the middle of the piece but may be located elsewhere (indicated by the star). In CAD grading, the stack point may also be called the point of origin and can be easily moved as needed.

I'm still working on my vocabulary list and guide. If there is a term you have heard and would like explained, please leave a comment below

*I realize I probably just used some vocabulary that the readers of this blog might not know. In any event, it illustrates the problem.

Grading manuals are similar, at least the ones I have used. They lack sufficient or clear explanations of the most basic of terms. Often times the manual writers skip sizing theory and jump to demonstrating their preferred grading method. This includes the much revered Jack Handford grading manual, the manual I still use and recommend today. Handford's book was the first that helped me understand grading but I recently reviewed the book and noticed the notations I made where I was confused.

One of my goals in writing my grading manual is to include a Grading 101 section. The above drawing is the illustration for two terms.

Nest - pattern pieces within a size range that are stacked along a common point or line. Indicated here by the horizontal line and star.

Stack point - the point at which pattern pieces are aligned, generally located in the middle of the piece but may be located elsewhere (indicated by the star). In CAD grading, the stack point may also be called the point of origin and can be easily moved as needed.

I'm still working on my vocabulary list and guide. If there is a term you have heard and would like explained, please leave a comment below

*I realize I probably just used some vocabulary that the readers of this blog might not know. In any event, it illustrates the problem.

August 05, 2013

The Organized Fashion Designer

I'm pleased to announce that my book, The Organized Fashion Designer, is now available for purchase. This book is a collection of guides and forms that I have developed and used while working in the fashion industry. Every fashion or sewn product business exists in some state of chaos. Out of desperation, I began to create various forms and organizing systems to keep track of all of the information needed to manufacture products. This led to simple tech packs that could be pulled together in an instant. I kept track of information using expensive database management software and simple paper and pencil forms. I have even used these forms with personal projects to keep my design space organized. Now I'm sharing these forms with new designers and home hobbyists in the hope that chaos can be organized.

The book includes blank forms and how to:

- Create a simple tech pack

- Develop grade rules

- Track every major step of your product development

- figure out how much your product costs to produce

- List sewing instructions

- Create a style number system

- Helpful industry resources

The book is available in three formats.

Spiral Bound

Saddle stitch (stapled pamphlet style)

eBook (PDF)

8.5" x 11" book

54 pages

or from Amazon.

5 star reviews on Etsy:

Thank you so much! Really helpful guide for designers - Linda

Love the ebook! Can't wait to get organized :) - Diane

Thank you!! This book is a great relief. It makes the paperwork look doable and dare I say appealing. - Trapper Jane

Thank you! Great resource! - Jess S

You can purchase the eBook or bundled selections from the book on Etsy.

July 19, 2012

Some more grading questions

I received some more grading questions.

Now there are pattern companies that draft their patterns either in CAD or scan in hand drafted patterns and add all the extra notations in Illustrator. The Big 4 do it that way. No problems there.

Grading by Pattern Shifting

I am wondering what you think of the section in Aldrich's book about grading? It seems like a simplified method in some ways and so I am wondering if for someone simply making the patterns (instead of the clothes) might this method do just fine?

There are different approaches to grading. Aldrich's "method" is similar to Handford, just presented in a different way. The movements of the pattern pieces is done in basically the same way as Handford. I have not graded a pattern using Aldrich's method, but I don't see that it would be a problem. Just keep in mind that her grade rules are based off her own sizing study of a British demographic. It may or may not work for your customer profile.

DIY or hire a pattern grader

Its not that I am adverse to putting in the extra time, but sometimes I wonder to myself if I am doing way more work than necessary in order to avoid "cutting corners" and making a product that in the end is below par.I've been grading patterns for over 15 years. I'm still learning. If you want a superior product, you will have to spend the time learning how it's done and gain necessary experience. People in business either hire someone to fill a knowledge or time gap or they spend a lot of time learning in the school of hard knocks. Grading is not especially difficult, but it does take time and effort to learn it. The best way to learn is by trying and doing. I don't mean to sound harsh, but there is no magic book or trick that will help you get what you want faster.

Can I grade patterns with Adobe Illustrator?

I am not drafting/grading using a cad program but am doing all my work by hand and in Adobe Illustrator if that helps you answer my question better.A lot of people ask me if they can use Adobe Illustrator for pattern making and grading. I suppose you could but to be honest, it's not for the faint of heart. I know there are indie pattern makers using Illustrator to do what you describe. But as a professional pattern maker and grader, Illustrator does not provide the level of accuracy and control that is needed for superior results. If given a choice, I would do all of my pattern making and grading by hand, or in other words with a pencil and paper.

Now there are pattern companies that draft their patterns either in CAD or scan in hand drafted patterns and add all the extra notations in Illustrator. The Big 4 do it that way. No problems there.

July 08, 2012

Designing and grading for a large size range

I get the following question from time to time:

Unfortunately, there is no other precise way to redraft your sample or base sizes except good old-fashioned pattern drafting. If you have some basic pattern blocks for each size range, then it is no big deal. Just starting out, though, it is a lot of work. It will take less time and become easier over time, so no worries. One thing to pay attention to are proportions. You may need to alter the design to accommodate the size while still giving the impression of the same overall design idea.

I am a self taught pattern drafter, drafting patterns for myself and myThere are several things. First, it is not unusual when designing children's clothing to cover a large size range. The reality is it is much more work than you would think. I would recommend reviewing my previous blog entries on grading, especially Creating a Grading Standard (also read the other grading tutorials, they'll be helpful).

kids for years. I decided to turn this into a business recently and am

creating a line of children's patterns for the home sewer. My size range

is 6m-10 and this is where my question is... Can you help me understand the process of redrafting the SAME style/pattern in my different base sizes? I get that I can't just take a size 5 and grade all the other sizes from

there. I own several popular pattern drafting books as well as 2 different

grading books and I can't seem to find this information anywhere. Any

information you can provide me would be SO HELPFUL. I am guessing there is some precise way to redraft my base sizes so the design doesn't change much. Can you shed some light on how they do this in the business? THANK YOU!

Unfortunately, there is no other precise way to redraft your sample or base sizes except good old-fashioned pattern drafting. If you have some basic pattern blocks for each size range, then it is no big deal. Just starting out, though, it is a lot of work. It will take less time and become easier over time, so no worries. One thing to pay attention to are proportions. You may need to alter the design to accommodate the size while still giving the impression of the same overall design idea.

May 02, 2012

Grading a skirt pattern

I sewed a skirt from a Burda pattern 2 years ago in desperation. I had gained weight and none of my skirts fit me anymore. 6 months later, I dropped all that weight and the skirt was simply too big. I liked the skirt pattern and it fit really well, but I had to grade the skirt pattern down in order to use it again.

In order to grade the skirt, I had to figure out the grade for Burda's patterns. I did this by looking at their measurement charts and comparing the sizes. With a little math I determined that Burda was using a 1.5 inch grade in the waist and hips. After comparing my measurements with the chart, I learned I only needed to go down one size.

So I pulled out my handy Jack Handford grading book and followed the instructions for grading a woman's skirt one size down. There are charts and instructions for a 1, 1.5, and 2 inch grade. It was so much easier to do than I expected. I knocked this out pretty quick. This book is now out of print, but if you can find it, buy it.

And I may be too much of a nerd, but I assigned a style number and created my own cutting spec for future reference. Now all I have to decide is which fabric to use to make up my next skirt.

In order to grade the skirt, I had to figure out the grade for Burda's patterns. I did this by looking at their measurement charts and comparing the sizes. With a little math I determined that Burda was using a 1.5 inch grade in the waist and hips. After comparing my measurements with the chart, I learned I only needed to go down one size.

So I pulled out my handy Jack Handford grading book and followed the instructions for grading a woman's skirt one size down. There are charts and instructions for a 1, 1.5, and 2 inch grade. It was so much easier to do than I expected. I knocked this out pretty quick. This book is now out of print, but if you can find it, buy it.

And I may be too much of a nerd, but I assigned a style number and created my own cutting spec for future reference. Now all I have to decide is which fabric to use to make up my next skirt.

February 09, 2011

Answers to some pattern grading questions

Tabitha of the Refugee Crafter sent me these questions. I thought her questions were enough for a separate blog entry.

What pattern pieces do I grade?

Thank you so much for all the patternmaking information you've provided on this blog! You've helped me make the jump from altering other's patterns to creating my own patterns this last year. (I purchased Aldrich's Metric Pattern Cutting for Children's Wear and Babywear

I'd love to now make the move to selling my own patterns but need a little direction in regards to grading which I am hoping you can provide. (I really am quite new to all this so please forgive the naivety of my questions!)

1. If I have created a ruffled shirt pattern in a size 12 months (just for example) can I grade each of its specific pattern pieces up or do I have to go back to the basic block, grade it up, and then alter it (again) to create another larger sized pattern? (Common sense tells me I should just be able to grade my pattern up, but I was confused by a line in the Aldrich book's grading section and thought I'd ask you for clarification. I hope my question makes sense.)

You would grade the pattern pieces for your style.

Can I use a computer software program to grade a pattern?

2. You often refer to grading on a CAD program. What is this program and is it widely available and reasonably priced? Does it have a steep learning curve? (I'm well versed in the vector-based Adobe Illustrator and the rest of the Creative Suite, would that help in learning this?)

There are several CAD programs out there specifically designed for apparel pattern making and grading. Unfortunately, they are not reasonably priced. Software packages start at about $10,000. The grading module is often times extra. If you are computer savvy and have used CAD programs in the past, then making the leap to an apparel specific CAD program is no big deal. For most though, it is a steep learning curve.

I have been following several independent pattern makers that make and sell patterns to the home sewing market. They are using Adobe Illustrator, so I guess it is possible to use that software to draft and grade your patterns. I don't endorse the practice because I don't know that Adobe Illustrator can create drafts that are accurate or precise. I suppose it is possible, but I've tried it in the past and it was an exercise in frustration. It would be a time consuming task regardless because many pattern making procedures are not automated. I would imagine grading would require the use of layers. Adobe Illustrator is not a technical drawing program.

The ideal procedure would be draft your patterns in CAD, grade them, and then export them to Adobe Illustrator to pretty them up. If you draft and/or grade by hand, you will have to digitize your patterns first. And remember that a CAD program will not teach you to grade. It's a tool not unlike a pencil and piece of paper.

What about the Jack Handford book?

3. You also mention Jack Handford's grading book. Is this book only useful if you are doing grading by hand or would it also be useful if used in conjunction with a CAD program? If a CAD program is out of the question is this my best bet?

I grade by hand and with CAD. I use the Jack Handford grading book

August 31, 2009

Comparing pattern shaping and children's sizes follow-up

Kathleen suggested that I post an update on a previous grading post I did about a year ago. You can read what I wrote previously at When Patterns Collide. In that post I suggested that it would be possible to combine the 24M and 2T and the 4T and the 4. My reasoning being that the 24M and the 2T are essentially the same sizes - why differentiate them? The subject is a little complex and perhaps controversial - at least to pattern making geeks. My goal was to reduce the work load. I was drafting and grading all of my patterns by hand. I am incredibly slow grading by hand. In addition, I was trying to solve one particular sizing problem that shows up in childrenswear, that is hard to illustrate. Since I shut down my Prairie Roses line, I am not knee deep in pattern making as I was a year ago. But perhaps it may be helpful to explain what I ended up doing.

Originally, I broke up my sizes into these ranges:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M, 24M - sample size 12M

2T, 3T, 4T - sample size 3T

4, 5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

These ranges are rather typical of what you will find in retail stores. When developing my patterns, I have to make and grade the patterns for each size range separately. You cannot make one set of patterns in one size and grade them up and down all the way. It won't work because that many sizes will cause minute grading errors and strange fit, especially on the smallest and largest sizes. As you define your grading and size measurements, you will find that the 24M and 2T and the 4T and 4 overlap. I followed the Jack Handford grading rules, which are pretty darn good, but end up with a result like this:

Originally, I broke up my sizes into these ranges:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M, 24M - sample size 12M

2T, 3T, 4T - sample size 3T

4, 5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

These ranges are rather typical of what you will find in retail stores. When developing my patterns, I have to make and grade the patterns for each size range separately. You cannot make one set of patterns in one size and grade them up and down all the way. It won't work because that many sizes will cause minute grading errors and strange fit, especially on the smallest and largest sizes. As you define your grading and size measurements, you will find that the 24M and 2T and the 4T and 4 overlap. I followed the Jack Handford grading rules, which are pretty darn good, but end up with a result like this:

In the picture above, the size 4 is laying on top of the size 4T. The size 4T is actually too long in length and too wide. I double checked all of my grading and there was no mistake. The size 4T was graded off my 3T and the size 4 off of the 5. The shaping of the sample size pattern pieces varied a little. The toddler was a little boxier because toddlers don't have any waist shaping, whereas a 5 year old does. If I were to leave my patterns this way, someone will eventually hang the two sizes next to each other and think there was some kind of manufacturing mistake. I needed to fix my patterns so that each size is incrementally bigger.

To do this, I rearranged my size ranges, combining some sizes:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M - sample size 12M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4 - sample size 3T

5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

The next thing I did was reworked the shaping of my toddler sizes to look more like the 4-6x range. I pulled the waist in some and made the armhole smaller. I made these shaping changes because I found that my toddler patterns were just a little too big. Now, I can lay all of my bodice pattern pieces in order and they get incrementally larger from the 3M to the 6x. Your patterns may look different, but it is worth comparing the sizes on the outside edges of your ranges to make sure you don't have something weird show up like I did.

Even though I combined some sizes, I kept this behind the scenes. My customers still saw all of the sizes separated out. If someone ordered a size 24M and another ordered a 2T, the dress would be exactly the same except for the size tag. I offered all of the sizes on my website so that customers would see something familiar. Perhaps it seems a little dishonest? I don't think so because in the real world a 24M child is the same size as a 2T and I was willing to take the chance. For what its worth, no one ever complained or returned those sizes for fit issues.

Now, I don't know that what I did is "the way it should be done". In the past though, I have had people question why the 24M was larger than the 2T and I had no explanation. Once I worked through grading all of my patterns by hand, it started to click in my head. The relationship of the shape of the pattern pieces, the grade, and body measurements are all connected.

To do this, I rearranged my size ranges, combining some sizes:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M - sample size 12M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4 - sample size 3T

5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

The next thing I did was reworked the shaping of my toddler sizes to look more like the 4-6x range. I pulled the waist in some and made the armhole smaller. I made these shaping changes because I found that my toddler patterns were just a little too big. Now, I can lay all of my bodice pattern pieces in order and they get incrementally larger from the 3M to the 6x. Your patterns may look different, but it is worth comparing the sizes on the outside edges of your ranges to make sure you don't have something weird show up like I did.

Even though I combined some sizes, I kept this behind the scenes. My customers still saw all of the sizes separated out. If someone ordered a size 24M and another ordered a 2T, the dress would be exactly the same except for the size tag. I offered all of the sizes on my website so that customers would see something familiar. Perhaps it seems a little dishonest? I don't think so because in the real world a 24M child is the same size as a 2T and I was willing to take the chance. For what its worth, no one ever complained or returned those sizes for fit issues.

Now, I don't know that what I did is "the way it should be done". In the past though, I have had people question why the 24M was larger than the 2T and I had no explanation. Once I worked through grading all of my patterns by hand, it started to click in my head. The relationship of the shape of the pattern pieces, the grade, and body measurements are all connected.

February 04, 2009

Who creates grade rules?

Some one asked me a grading question the other day. She wanted to know who creates grade rules?

A pattern maker, grader, or you could make the grade rules. If you choose to make the grade rules yourself, I have some guides available in The Organized Fashion Designer and The Simple Tech Pack. It's harder with children's clothing because there isn't as much standardization. An experienced grader should have some standard charts or be able to develop rules off of your measurement charts. I would personally start developing grade rules by referencing the Jack Handford book and make modifications as needed. I would only let a pattern maker or grader do it who has experience with it.

You can buy measurement charts from ASTM as a place to start. The ASTM measurement charts for children are probably the best resource for children's body measurements. Be cautious of using free charts found on the Internet. I have seen free measurement charts on the Internet riddled with inconsistencies that could lead to serious errors.

If you have time, you may want to sew up the smallest and largest sizes just to double check the grade and sizing. It doesn't have to be in your production fabric or anything. A fitting is the only way to know if your grade is correct. You won't need to do this on every style or very often. Kind of important when starting out though.

Labels:

ASTM,

Grade rules,

Grading,

Measurement charts,

Patternmaking,

References,

Size Charts,

Sizing

September 02, 2008

Comparing pattern shaping and children's sizes

As many children's wear designers know, children's clothing has a lot of sizes. It can become quite the dilemma when trying to decide which sizes to offer. Some DE's offer their styles in as many as 21 sizes. Way back in 2006 I suggested a theory to reduce the number of sizes by combining or eliminating some of them. You may want to go back and review the entry Too Many Sizes and other related entries to see how I have arrived at today.

Anyway, I have tried to put the theory into practice and I have made some progress. I only offer my styles in sizes 3M to 6x. I am still working on the grades for the 4-6x styles, so I am nearly there. My sizes break down like this:

3M, 6M, 9M*, 12M, 18M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4

5, 6, 6x

I don't really consider the 9M as a true size. It is a half size between the 6M and 12M and is graded by splitting the grade between the 6M and 12M. The 24M and 2T are essentially the same as are the 4T and 4 - those sizes have been combined for grading purposes. My website still delineates the combined sizes as separate sizes.

This blog entry is not a discussion on the why and wherefores of children's sizing - a surprisingly complex and controversial topic. Instead, I wanted to show a possible grading/pattern problem that shows up now and then. I have been grading and comparing my basic bodice blocks. You should do this too because someone will eventually see the problem and it will be more difficult to fix.

I have drafted my basic bodice block three times, in each of my sample sizes for each of my size ranges - 12M, 3T, 5. (BTW, you can't use the same pattern piece and grade it in all the sizes. Believe me, that is one large headache). The next step is to grade each range separately. Keep in mind that each sample size will have slightly different shaping, but the general shape and proportion should be related.

Before getting too far, the outer fringes of each size range should be compared. For example, the size 18M should be smaller than the 24M/2T and the size 4T/4 should be smaller than the 5. Originally, I had graded the size 4T and 4 separately. In other words the 4T was based off the 3T sample and the 4 was based off the 5. The reason I combined the 4T and 4 was because the shape and overall size was so similar it was a duplication in effort, and I also ran into the problem where the 4T was actually larger than the 4. If you do separate out the sizes than the 4T must be smaller than the 4. If you don't check your grades, someone will bring two dresses to you and say the patterns are wrong, size labels are switched or some other problem.

In the photos below you can see the problem more clearly. In the top picture, the size 4 is laying on top of the 4T. You can see the 4 is smaller than the 4T. In the bottom picture the 4T is on top of the 4 and it is clearly longer with a larger armhole.

To solve this problem, I have been reworking my toddler patterns. I started by combining sizes 4T and 4 so I have one less size to grade. Next my toddler bodices were redrafted to have a shape similar to the 5 (less boxy, smaller armhole). Finally, I regraded the toddler patterns. This is still a work in progress, but the results are much better - each size is progressively larger.

I had the same problem with my size 18M and 24M/2T. In this case it wasn't a grading problem. Instead my infant patterns were proportionally too long compared to the toddler. I fixed this by shortening the bodice slightly.

Anyway, the point is that you should make sure and check the sizes on the outer fringes of each size range and make adjustments so that each size is progressively larger. You can adjust the grade rules (much easier in CAD, btw) or change the shape of the patterns.

(I am ignoring the idea that in the real world an 18M child could be larger than a 24M child. If that is the case, a parent would buy a larger size than 18M and just complain about the craziness of US sizing standards. When I did private label programs for the big box retailers their grade/POM charts progressively got larger with each size. Logically it makes sense even if reality is very different. Anyway, you can allow your sizes to overlap if you want, you'll just need to have an explanation as to why when a sewing contractor becomes confused.).

Anyway, I have tried to put the theory into practice and I have made some progress. I only offer my styles in sizes 3M to 6x. I am still working on the grades for the 4-6x styles, so I am nearly there. My sizes break down like this:

3M, 6M, 9M*, 12M, 18M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4

5, 6, 6x

I don't really consider the 9M as a true size. It is a half size between the 6M and 12M and is graded by splitting the grade between the 6M and 12M. The 24M and 2T are essentially the same as are the 4T and 4 - those sizes have been combined for grading purposes. My website still delineates the combined sizes as separate sizes.

This blog entry is not a discussion on the why and wherefores of children's sizing - a surprisingly complex and controversial topic. Instead, I wanted to show a possible grading/pattern problem that shows up now and then. I have been grading and comparing my basic bodice blocks. You should do this too because someone will eventually see the problem and it will be more difficult to fix.

I have drafted my basic bodice block three times, in each of my sample sizes for each of my size ranges - 12M, 3T, 5. (BTW, you can't use the same pattern piece and grade it in all the sizes. Believe me, that is one large headache). The next step is to grade each range separately. Keep in mind that each sample size will have slightly different shaping, but the general shape and proportion should be related.

Before getting too far, the outer fringes of each size range should be compared. For example, the size 18M should be smaller than the 24M/2T and the size 4T/4 should be smaller than the 5. Originally, I had graded the size 4T and 4 separately. In other words the 4T was based off the 3T sample and the 4 was based off the 5. The reason I combined the 4T and 4 was because the shape and overall size was so similar it was a duplication in effort, and I also ran into the problem where the 4T was actually larger than the 4. If you do separate out the sizes than the 4T must be smaller than the 4. If you don't check your grades, someone will bring two dresses to you and say the patterns are wrong, size labels are switched or some other problem.

In the photos below you can see the problem more clearly. In the top picture, the size 4 is laying on top of the 4T. You can see the 4 is smaller than the 4T. In the bottom picture the 4T is on top of the 4 and it is clearly longer with a larger armhole.

To solve this problem, I have been reworking my toddler patterns. I started by combining sizes 4T and 4 so I have one less size to grade. Next my toddler bodices were redrafted to have a shape similar to the 5 (less boxy, smaller armhole). Finally, I regraded the toddler patterns. This is still a work in progress, but the results are much better - each size is progressively larger.

I had the same problem with my size 18M and 24M/2T. In this case it wasn't a grading problem. Instead my infant patterns were proportionally too long compared to the toddler. I fixed this by shortening the bodice slightly.

Anyway, the point is that you should make sure and check the sizes on the outer fringes of each size range and make adjustments so that each size is progressively larger. You can adjust the grade rules (much easier in CAD, btw) or change the shape of the patterns.

(I am ignoring the idea that in the real world an 18M child could be larger than a 24M child. If that is the case, a parent would buy a larger size than 18M and just complain about the craziness of US sizing standards. When I did private label programs for the big box retailers their grade/POM charts progressively got larger with each size. Logically it makes sense even if reality is very different. Anyway, you can allow your sizes to overlap if you want, you'll just need to have an explanation as to why when a sewing contractor becomes confused.).

Labels:

Analysis,

Clothing for Children,

Comparison,

Grading,

Patternmaking,

Size Charts,

Sizing,

Tutorials

April 18, 2008

Grading Complex Styles pt. 2

Part 2 of this series continues the discussion of how to grade complex styles. It is not necessary to have the Handford book to understand the concept, but some experience with grading would be helpful.

This part of the series was going to contain a lot of explanation with lots of examples. There are two reasons that I held off on that. The first is I am considering writing a book on the subject. I am sure it will be a best seller and I will be able to retire early [eye-roll]. The second is that it would be impossible to discuss every possible scenario. It would be best to explain the principle and let you work out your specific grading problem on your own. You will benefit with having to struggle with the material and learn lots in the process.

Just a side note, these pieces have been simplified, no darts or extra gathers. I am also ignoring the seam allowances. The grading is done the same way regardless. This demonstration only shows how to figure out a length grade. The same principle works for widths.

Anyway, let's move on to the examples....

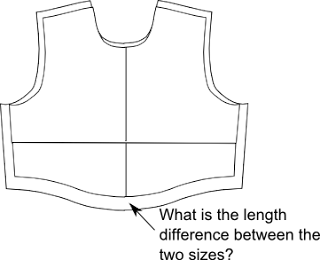

In order to grade a complex style, you need to have basic blocks that are already graded. On top I have a basic block that is already graded. Below that is my ungraded pattern pieces for a bodice with a mid-riff.

There are many ways to determine the total length grade. In this case, I just want to know what the length difference is between the graded basic block and the ungraded pieces. I want to grade my pieces up to the next larger size. To do this, I just lay the ungraded pattern pieces on top of the next size and align the pieces along the horizontal and vertical axis. My drawings are missing the horizontal, but you can pretend there is a line that runs from the side-seam/armscye points across the pieces. BTW if you would rather, you can figure all this out mathematically....

Once you know the length grade difference, you can then decide where you want that length growth to occur on your ungraded pattern pieces. In the examples below, you can have that length split between the two pieces or all of it in one piece or the other (shown in red).

The question you have to ask is:

This is where the beauty of computerized grading happens. I can play with the grade as much as I want - plugging in different numbers until the proportions look the way I want for each size. Hand grading would be a little more complex. The more complex the style, the more difficult the grade can become when doing it by hand. Handford's suggestion to tape the pieces together with long strips of tagboard can work in hand grading. The grader will have to determine if additional grade points should be added and how much movement should occur. This can be done by using Handford's red lines of distribution. Sophisticated manipulation at each grade point can only occur in CAD.

Still the principle works the same regardless of how complex the style or method.

1. Determine your total length/width grades.

2. Calculate the length/width difference between sizes at the grade points.

3. Decide where the growth should occur by comparing the total grade and the difference between each size at the needed grade points. What proportionally looks correct? How is my fit affected?

This part of the series was going to contain a lot of explanation with lots of examples. There are two reasons that I held off on that. The first is I am considering writing a book on the subject. I am sure it will be a best seller and I will be able to retire early [eye-roll]. The second is that it would be impossible to discuss every possible scenario. It would be best to explain the principle and let you work out your specific grading problem on your own. You will benefit with having to struggle with the material and learn lots in the process.

Just a side note, these pieces have been simplified, no darts or extra gathers. I am also ignoring the seam allowances. The grading is done the same way regardless. This demonstration only shows how to figure out a length grade. The same principle works for widths.

Anyway, let's move on to the examples....

In order to grade a complex style, you need to have basic blocks that are already graded. On top I have a basic block that is already graded. Below that is my ungraded pattern pieces for a bodice with a mid-riff.

There are many ways to determine the total length grade. In this case, I just want to know what the length difference is between the graded basic block and the ungraded pieces. I want to grade my pieces up to the next larger size. To do this, I just lay the ungraded pattern pieces on top of the next size and align the pieces along the horizontal and vertical axis. My drawings are missing the horizontal, but you can pretend there is a line that runs from the side-seam/armscye points across the pieces. BTW if you would rather, you can figure all this out mathematically....

Once you know the length grade difference, you can then decide where you want that length growth to occur on your ungraded pattern pieces. In the examples below, you can have that length split between the two pieces or all of it in one piece or the other (shown in red).

The question you have to ask is:

This is where the beauty of computerized grading happens. I can play with the grade as much as I want - plugging in different numbers until the proportions look the way I want for each size. Hand grading would be a little more complex. The more complex the style, the more difficult the grade can become when doing it by hand. Handford's suggestion to tape the pieces together with long strips of tagboard can work in hand grading. The grader will have to determine if additional grade points should be added and how much movement should occur. This can be done by using Handford's red lines of distribution. Sophisticated manipulation at each grade point can only occur in CAD.

Still the principle works the same regardless of how complex the style or method.

1. Determine your total length/width grades.

2. Calculate the length/width difference between sizes at the grade points.

3. Decide where the growth should occur by comparing the total grade and the difference between each size at the needed grade points. What proportionally looks correct? How is my fit affected?

Labels:

Golden Mean,

Grading,

Growth,

Patternmaking,

Proportion,

Sewing Patterns,

Size Charts,

Sizing

April 13, 2008

Grading Complex Styles pt. 1

Part 1 of this grading series will make more sense if you have a copy of Jack Handford's Professional Pattern Grading book. Unfortunately, the book is now out of print. Still, this entry may be helpful in grading complex styles, especially part 2...

An anonymous reader left this comment:

This is a good question and can be confusing. The first thing I had to do was go back and look at Handford's book to see those red lines. Sometimes when I read a technical book my eyes glaze over and I skim until I find the info I am looking for. To be honest, I have had to study Handford's book several times to grasp what he is saying. In any event, I couldn't recall those red lines....

The red lines are illustrated on page 1-2 of Handford's book. He uses the red lines to indicate where a pattern grows or shrinks. The rest of the book has more illustrations of basic pattern pieces that show this. The key is to read page 3:

In other words, a grader could draw those lines of distribution on each pattern piece and then cut the pattern apart to spread or overlap them for the next size. He is absolutely right that such a task would be extremely time consuming, error prone and tedious. This is the failure of the Price/Zamkoff book on grading because this is how they explain grading. It was the primary reason I was so confused about grading too. If you were to grade by hand, could you imagine making duplicate copies of your base pattern so you could cut it apart? You would then need to carefully align the pieces, tape them securely, redraw the pattern, and cut it out. Then you would have to start the whole process over again for the next size. Yikes!

I don't mean to be so hard on Price/Zamkoff because they explain the concept of grading correctly. The problem is that it is not practical, even in a CAD environment.

I am not sure why Handford places those red lines in his illustrations other than to illustrate where the growth is occurring as you grade using his method. In his method, you move a pattern piece a certain direction at each grade point. The grade points are related to those red lines but are actually located at a pattern edge, usually a corner or mid-point.

Anyway, the reason I didn't remember seeing those red lines is because I ignored them. As a CAD grader I simply select a point and enter in the amount of growth. In my head I know a piece is growing in the middle of the pattern even when I assign the growth to an outside corner or point.

Anyway, I have blathered too long.... The commenter is correct that with complex styles the growth/shrinkage must be placed properly. Handford illustrates a slightly more complex style of a bodice with midriff on pages 93-94. The pieces are taped together with strips of tagboard and graded at the same time. On page 89 Handford makes the suggestion of placing the style on a form to determine where growth/shrinkage should occur. While his suggestion is valid, it is difficult to make the conceptual leap from a 3D form with lines to a table top with flat pattern pieces.

I have never done this. Partly because I have only graded children's pattern pieces. There have only been a handful of styles that I would consider very complex. Since I did this on CAD I had the luxury of playing around with the grading until I felt it was correct. I came up with my own method that works for me. It is not much different from putting a jigsaw puzzle together and only involves a little bit of math.

CAD makes grading complex styles very easy. Unfortunately, the night is getting late and so a complete explanation will have to wait. For now, you must know your total width and length grades, say for a bodice pattern piece. If you have a bodice with a midriff and the total length grade is 1" (I don't know I am making this up...), divide the total length grade between the two pieces so that the growth looks proportionally correct.... Anyway, more later...

An anonymous reader left this comment:

I love your blog. Thank you so much for all the information. I've recently started grading patterns. I can grade simple styles by following Handford or other books' steps no problem. But when it comes to complex designs, such as clothing that has unusual shapes and consists of multiple panels, I have trouble placing the "distribution lines" (red lines in Handford's book) on the patterns. Handford suggests by putting the patterns on the mannequins and draw the red lines. But sometimes it isn't practical as I'm using a CAD program.

Any suggestions?

This is a good question and can be confusing. The first thing I had to do was go back and look at Handford's book to see those red lines. Sometimes when I read a technical book my eyes glaze over and I skim until I find the info I am looking for. To be honest, I have had to study Handford's book several times to grasp what he is saying. In any event, I couldn't recall those red lines....

The red lines are illustrated on page 1-2 of Handford's book. He uses the red lines to indicate where a pattern grows or shrinks. The rest of the book has more illustrations of basic pattern pieces that show this. The key is to read page 3:

Obviously the cutting and spreading or overlapping of each part of each pattern to grade it one size up or one size down would be far too time consuming and invite much chance for error to be practical.

In other words, a grader could draw those lines of distribution on each pattern piece and then cut the pattern apart to spread or overlap them for the next size. He is absolutely right that such a task would be extremely time consuming, error prone and tedious. This is the failure of the Price/Zamkoff book on grading because this is how they explain grading. It was the primary reason I was so confused about grading too. If you were to grade by hand, could you imagine making duplicate copies of your base pattern so you could cut it apart? You would then need to carefully align the pieces, tape them securely, redraw the pattern, and cut it out. Then you would have to start the whole process over again for the next size. Yikes!