This is part three of an ongoing discussion about N. A. Schofield's

article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. Part one

is here, part two here. I recommend reading the previous parts of this series before reading this one.

So what were the results of Schofield's experiment? I can't reproduce the actual results here, but it was something like this.

Imagine the square is a bodice pattern piece in one size. The star is supposed to be the same pattern piece but graded to the next size. Clearly, the two shapes have no proportional relationship to each other. The problem is further compounded by a different grade for corresponding pieces.

Imagine these are front and back bodice pattern pieces. Each corresponding pattern piece was graded separately based on the measurement data for that body location. Now imagine trying to sew the front and back together. It can't be done. Schofield freely admits the difficulty in the results. Though she also believes we need to learn how to deal with new shapes in pattern pieces in order to achieve superior fit.

Schofield's experiment left me with a lot of questions. I did not understand completely why she rejected the ASTM measurement data, nor why she went back to essentially raw data. Her grading methodology left me a bit confused. The results were clearly not suitable for industry application. Superior fit is the holy grail of fashion, but I'm not convinced that grading is the entire source of the problem. Superior fit, for each individual might only be achieved on an individual basis. In this case, 3D body scanning and customized clothing is the answer, but is it practical?

I would like to see this experiment repeated. The factors that will impact additional experiments are the measurement data and grading methodology. Why not use ASTM measurement data? Why not use traditional grading methods? I always support those who are willing to test ideas and theories. This was a worthy attempt by Schofield to ask important why and how questions.

Showing posts with label Measurement charts. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Measurement charts. Show all posts

May 26, 2015

April 16, 2015

Grading from body measurements pt. 2

This is part two of an ongoing discussion about N. A. Schofield's article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. Part one is here.

My initial reaction to the idea of grading from body measurements was, "Well, of course we should." And in fact, we do for children's clothing. It seemed rather obvious to me to look at children's clothing as a model. Children's sizing is based on the idea of growth, meaning that the measurement intervals between sizes are not always consistent.

Let's look at an example for a 4-6x size range.*

For sizes 4, 5, 6, 6x

Chest: 23, 24, 25, 25.5

Waist: 21.5, 22, 22.5, 23

Hip: 23.5, 24.5, 25.5, 26.5

The grade works out to be, choosing size 5 as the base size:

Chest: 1, 0, 1, 1.5

Waist: 0.5, 0, 0.5, 0.5

Hip: 1, 0, 1, 1

In this example, we have a 1" chest grade, except for size 6x which is 1.5". The waist is a 0.5" inch grade and the hip returns to a 1" grade for all sizes. Each body measurement area has it's own grade.

In women's clothing a 2" grade means that the interval change between the sizes will be 2" for chest, waist, and hips. Though even this isn't true across all brands, and you will find variations. (IMO, this is a good thing)

I don't know the history of women's sizing well enough to explain how this mode of practice came to be nor exactly why. It is clear that it does make grading, especially hand grading, much easier in practice. It is also unclear to me that grading is the source of our fitting woes. Nevertheless, it does make sense to me to go back and look at body measurements and devise a more precise grade rule.

The question then becomes, which body measurements do we use? In my children's example above, the numbers are still nice and easy to work with. The body measurements have been intentionally manipulated to be easy to work with. Raw measurement data was averaged, sorted, and studied to arrive at some numbers. Those numbers were not easy to work with, so a group of industry professionals sat down and made them that way. They modified certain measurements by about 1/8" to achieve consistency. Their modifications were rather minor and easily fall within a statistical margin of error. If you read their reasoning, it makes sense. This manipulation of measurement data for ease of use continues today in more modern measurement studies. It seems deceitful, but at the end of the day is infinitely practical. ASTM D4910 inherits this method of data handling from the measurement studies done in the 1940s, but does provide some updated measurements.

Looking at the Misses body measurement chart, ASTM D5585, it seems to be arranged and handled in the same way as the children's body measurement chart. IOW, the chart does not show a 1, 1.5, or 2 inch grade in the body measurements. It is a lot like the children's example above. There does seem to be a disconnect between measurement data and grading, at least on the surface. Individual companies will decide how to interpret and implement measurement data, and therefore their grade rules. (IMO, I think this is a good thing). And some will use a 2 inch grade, and some will not.

So what measurement data did Schofield use? She rejected the ASTM charts and created her own version of measurements derived from body measurement studies. This presented a problem because measurement studies do not always include the measurements needed for pattern making and grading. Schofield did not normalize the data, in other words make it easy to work with. Also she had to figure out how to deal with missing measurement data. I no longer have a copy of the article and can't look back, but Schofield selected certain measurements over others. How and why she handled those measurements puzzled me.

I believe Schofield's goal was to remove the idea of maintaining an ideal proportion or predictable pattern shape. She wanted to see what the body measurements really did between sizes.

Her results were almost predictable. More on that later.

*These measurements come from the withdrawn child measurement standard CS151-50. Measurements are in inches.

My initial reaction to the idea of grading from body measurements was, "Well, of course we should." And in fact, we do for children's clothing. It seemed rather obvious to me to look at children's clothing as a model. Children's sizing is based on the idea of growth, meaning that the measurement intervals between sizes are not always consistent.

Let's look at an example for a 4-6x size range.*

For sizes 4, 5, 6, 6x

Chest: 23, 24, 25, 25.5

Waist: 21.5, 22, 22.5, 23

Hip: 23.5, 24.5, 25.5, 26.5

The grade works out to be, choosing size 5 as the base size:

Chest: 1, 0, 1, 1.5

Waist: 0.5, 0, 0.5, 0.5

Hip: 1, 0, 1, 1

In this example, we have a 1" chest grade, except for size 6x which is 1.5". The waist is a 0.5" inch grade and the hip returns to a 1" grade for all sizes. Each body measurement area has it's own grade.

In women's clothing a 2" grade means that the interval change between the sizes will be 2" for chest, waist, and hips. Though even this isn't true across all brands, and you will find variations. (IMO, this is a good thing)

I don't know the history of women's sizing well enough to explain how this mode of practice came to be nor exactly why. It is clear that it does make grading, especially hand grading, much easier in practice. It is also unclear to me that grading is the source of our fitting woes. Nevertheless, it does make sense to me to go back and look at body measurements and devise a more precise grade rule.

The question then becomes, which body measurements do we use? In my children's example above, the numbers are still nice and easy to work with. The body measurements have been intentionally manipulated to be easy to work with. Raw measurement data was averaged, sorted, and studied to arrive at some numbers. Those numbers were not easy to work with, so a group of industry professionals sat down and made them that way. They modified certain measurements by about 1/8" to achieve consistency. Their modifications were rather minor and easily fall within a statistical margin of error. If you read their reasoning, it makes sense. This manipulation of measurement data for ease of use continues today in more modern measurement studies. It seems deceitful, but at the end of the day is infinitely practical. ASTM D4910 inherits this method of data handling from the measurement studies done in the 1940s, but does provide some updated measurements.

Looking at the Misses body measurement chart, ASTM D5585, it seems to be arranged and handled in the same way as the children's body measurement chart. IOW, the chart does not show a 1, 1.5, or 2 inch grade in the body measurements. It is a lot like the children's example above. There does seem to be a disconnect between measurement data and grading, at least on the surface. Individual companies will decide how to interpret and implement measurement data, and therefore their grade rules. (IMO, I think this is a good thing). And some will use a 2 inch grade, and some will not.

So what measurement data did Schofield use? She rejected the ASTM charts and created her own version of measurements derived from body measurement studies. This presented a problem because measurement studies do not always include the measurements needed for pattern making and grading. Schofield did not normalize the data, in other words make it easy to work with. Also she had to figure out how to deal with missing measurement data. I no longer have a copy of the article and can't look back, but Schofield selected certain measurements over others. How and why she handled those measurements puzzled me.

I believe Schofield's goal was to remove the idea of maintaining an ideal proportion or predictable pattern shape. She wanted to see what the body measurements really did between sizes.

Her results were almost predictable. More on that later.

*These measurements come from the withdrawn child measurement standard CS151-50. Measurements are in inches.

April 09, 2015

Grading from body measurements pt. 1

Pattern grading is the process by which new sizes are developed from an existing pattern. There are various methods or processes used to grade a pattern. These methods include slash-and-spread, shifting, and CAD. At the end of the day, each method accomplishes the same thing, a new size.

The apparel industry has received a lot of criticism for their sizing, especially of women's clothing. At it's core, sizing goes hand-in-hand with pattern grading. You have to define your sizes in order to grade a pattern. In order to grade a pattern you have to know body measurements for each size. The common grade rules for women's apparel is the 1", 1.5" and 2" grade rules used in the United States. Similar grade rules are found in Europe and the UK. The primary criticism is that these grade rules are not based on anthropometric data, or actual body measurements. Instead these grade rules are just pulled out of a hat without regard to women or their fitting needs. These arbitrary grade rules are merely for the convenience of industry.

This is the point of view taken by N. A. Schofield in her article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. The goal of her research was to test the idea of creating grade rules based on actual body measurements rather than an arbitrary grade rule. There has been a lot of criticism of the industry over sizing and it is a worthy goal to research alternatives. Asking the why questions. Why does the apparel industry do things the way they do? Why do we grade women's clothing this way? Can we do it differently? I've asked a lot of these same questions as I've looked at children's clothing. When I started out, I didn't understand the why and sometimes the answer was not satisfying. I can totally get behind Schofield's motivation to try and find an answer.

And yet, I feel like I am setting up to be very critical of Schofield's research and I don't want to give the impression, as an industry professional, that even asking the questions were wrong. She was right to ask the question and to test an alternative. The results of her research are interesting and ironically (and indirectly) add support to current practices.

So here are some of Schofield's main arguments:

1. 1", 1.5", and 2" grade rules are not based on anthropometric data. Meaning it is not based on body measurements or the proportional relationships between body parts/areas. These grade rules were intended for the convenience and ease of hand grading.

2. Grade rules should be derived from body measurements. This means that grade breaks between bust, waist, and hips should not be consistent. Instead of a 34-36-38 chest measurement, we should be seeing a 34-35.5-38 (just as an example), chest measurement.

3. Size prediction and also body measurement prediction needs refinement. This idea is rather complex. Body measurement studies create a lot of raw data. In order to make sense of it, statisticians will test size prediction by using one or two body measurements. So can you predict the overall body size by using just the height or chest measurement? And if you do that, what influence does that have on other body measurements? If a person gets taller, do they also get wider? It is a complex question and not easily answered because there are so many variables. Statisticians bring order to raw measurement data so that we can organize the body measurements into sizes. They do this by averaging and, in some cases, normalizing the data so we can work with it easily. Schofield implies that we should just rely on the raw measurement data.

The ultimate goal of this study was to improve overall fit of women's apparel by basing grade rules on actual body measurements. I'll have to break up my review of this study into multiple blog entries because I have a lot to say about it. So stay tuned.

The apparel industry has received a lot of criticism for their sizing, especially of women's clothing. At it's core, sizing goes hand-in-hand with pattern grading. You have to define your sizes in order to grade a pattern. In order to grade a pattern you have to know body measurements for each size. The common grade rules for women's apparel is the 1", 1.5" and 2" grade rules used in the United States. Similar grade rules are found in Europe and the UK. The primary criticism is that these grade rules are not based on anthropometric data, or actual body measurements. Instead these grade rules are just pulled out of a hat without regard to women or their fitting needs. These arbitrary grade rules are merely for the convenience of industry.

This is the point of view taken by N. A. Schofield in her article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. The goal of her research was to test the idea of creating grade rules based on actual body measurements rather than an arbitrary grade rule. There has been a lot of criticism of the industry over sizing and it is a worthy goal to research alternatives. Asking the why questions. Why does the apparel industry do things the way they do? Why do we grade women's clothing this way? Can we do it differently? I've asked a lot of these same questions as I've looked at children's clothing. When I started out, I didn't understand the why and sometimes the answer was not satisfying. I can totally get behind Schofield's motivation to try and find an answer.

And yet, I feel like I am setting up to be very critical of Schofield's research and I don't want to give the impression, as an industry professional, that even asking the questions were wrong. She was right to ask the question and to test an alternative. The results of her research are interesting and ironically (and indirectly) add support to current practices.

So here are some of Schofield's main arguments:

1. 1", 1.5", and 2" grade rules are not based on anthropometric data. Meaning it is not based on body measurements or the proportional relationships between body parts/areas. These grade rules were intended for the convenience and ease of hand grading.

2. Grade rules should be derived from body measurements. This means that grade breaks between bust, waist, and hips should not be consistent. Instead of a 34-36-38 chest measurement, we should be seeing a 34-35.5-38 (just as an example), chest measurement.

3. Size prediction and also body measurement prediction needs refinement. This idea is rather complex. Body measurement studies create a lot of raw data. In order to make sense of it, statisticians will test size prediction by using one or two body measurements. So can you predict the overall body size by using just the height or chest measurement? And if you do that, what influence does that have on other body measurements? If a person gets taller, do they also get wider? It is a complex question and not easily answered because there are so many variables. Statisticians bring order to raw measurement data so that we can organize the body measurements into sizes. They do this by averaging and, in some cases, normalizing the data so we can work with it easily. Schofield implies that we should just rely on the raw measurement data.

The ultimate goal of this study was to improve overall fit of women's apparel by basing grade rules on actual body measurements. I'll have to break up my review of this study into multiple blog entries because I have a lot to say about it. So stay tuned.

March 05, 2015

Communicating size and fit through size labels and charts

The primary way most clothing brands communicate size information is through a size label. This works in most retail settings. Online (and print catalog) clothes shopping adds the benefit of including an easy to use, sometimes interactive size chart. Additional instructions on how to measure yourself is also helpful.

None of these solutions are completely fool proof. First, the manufacturer interprets and adapts measurement data to meet the needs of their identified customer. This means they have created and implemented a size system in anticipation of what their customer wants. But a customer may want something to be closer/looser fitting, and shorter/longer lengths than the manufacturer. How does one balance size and fit for a diverse population with ever shifting expectations?

The current trend among new fashion companies is to design for a very narrow customer profile. By targeting a very specific customer, the manufacturers can optimize the fit of their brand to their customer. Larger big box brands have to fit a wide range of body shapes and sizes and their clothes will never fit as well as a more exclusive brand. In some cases a manufacturer will modify their sizes for an existing size system, so that they change what a size means for their target market. In other words, a size 8 for one brand will mean something entirely different for another. This is why there is so much variation in the marketplace between brands.

On the surface this sounds like vanity sizing run amok. If manufacturers change the underlying sizes to fit their version of a size, then surely they are deceiving us into believing we are a smaller size than we truly are. Truth in advertising and all that, right?

The problem with only one size standard across brands is that it does not allow for variation. Women in particular have a large variety of body shapes and sizes. Because manufacturers are free to adapt to meet the needs of their customers having multiple versions of a size will allow people to find the version that fits them best. Once they do, and if the styling is right, they will become loyal customers.

The problem comes back to how to communicate that to the customer. As I said at top, providing more information helps the customer to make a more informed choice. And that is the true challenge.

*This blog entry is part of my on going review of Sizing in Clothing, and is a discussion inspired by the article, Communication of sizing and fit by J. Chun. This article goes into a little more depth about how sizes have evolved and what they might mean.

| ||

| A pictogram showing body dimensions for a specific size. |

The current trend among new fashion companies is to design for a very narrow customer profile. By targeting a very specific customer, the manufacturers can optimize the fit of their brand to their customer. Larger big box brands have to fit a wide range of body shapes and sizes and their clothes will never fit as well as a more exclusive brand. In some cases a manufacturer will modify their sizes for an existing size system, so that they change what a size means for their target market. In other words, a size 8 for one brand will mean something entirely different for another. This is why there is so much variation in the marketplace between brands.

On the surface this sounds like vanity sizing run amok. If manufacturers change the underlying sizes to fit their version of a size, then surely they are deceiving us into believing we are a smaller size than we truly are. Truth in advertising and all that, right?

The problem with only one size standard across brands is that it does not allow for variation. Women in particular have a large variety of body shapes and sizes. Because manufacturers are free to adapt to meet the needs of their customers having multiple versions of a size will allow people to find the version that fits them best. Once they do, and if the styling is right, they will become loyal customers.

The problem comes back to how to communicate that to the customer. As I said at top, providing more information helps the customer to make a more informed choice. And that is the true challenge.

*This blog entry is part of my on going review of Sizing in Clothing, and is a discussion inspired by the article, Communication of sizing and fit by J. Chun. This article goes into a little more depth about how sizes have evolved and what they might mean.

February 10, 2015

Size standardization for clothing

In academic circles there is the idea that we need one measurement and sizing standard to solve all our fitting problems. A top down approach with no allowance for variation. Customers often complain that manufacturers have no idea what they are doing because nothing ever fits. Manufacturers face an enormous challenge in trying to interpret size specifications while at the same time meeting the needs of their customers. The more I read about sizing the more chaotic it seems. At the end of the day there is more than one way to look at size standardization, and I think only one battle to fight.

One standard to rule them all

Yes, the idea that one standard can be established for everyone. By forcing compliance we will have peace on earth, and yes, our clothes will fit! Considering the variety of shapes and sizes in the United States alone, the idea is really a fantasy.

Loosely conforming to a standard while yet adapting to meet a customer's need.

Even if one standard to rule them all is unrealistic, we still need a standard. ASTM and the latest Sizing USA study have provided us with a standard that any manufacturer can use (for a price, of course). These measurement and sizing specs can act as a guide, a place to start. As a manufacturer develops their customer profile, they can adapt these standards to meet the needs of their customer.

Over the years, it's important to compare your product against these standards. I've seen patterns and sizing drift from these standards naturally through errors. These errors are not intentional, they just happen and can easily pass from one style to the next. So a careful study and comparison can bring things back. This includes measuring fit models and comparing them against the standard and analyzing customer returns due to fit issues.

In-house size standardization

Once a sizing standard is established for a brand, it is important to adhere to that standard during product development. As an example, all new pants styles have the same finished length and waist sizes as specified. Variations in fit can come from multiple sources due to fabric variations (or problems), construction issues (taking too big/small a seam allowance, cutting errors), or variations in a pattern. You have to be careful not to draft a pattern from scratch every time. Pattern makers in the industry will use the patterns from an already proven style to develop the new style. This practice ensures consistent fit across styles. A quality control process through each step of development and production is necessary to find problems before they become big ones.

A few words on vanity sizing

Vanity sizing implies that a manufacturer wilfully chooses to ignore a size standard and relabel a size smaller than it actually is. I do not believe there is a vast conspiracy to do this intentionally. Instead I think manufacturers are trying to meet the needs of their customers while trying to conform to a standard.

*This blog entry was inspired from my reading in the book Sizing in Clothing and more specifically the article Sizing Standardization by K. L. LaBat. I made very few notes on this article and don't remember much of what I read. I did make a note that LaBat tried to prove the existence of vanity sizing by studying children's age-based sizing. I thought the argument was rather weak.

One standard to rule them all

Yes, the idea that one standard can be established for everyone. By forcing compliance we will have peace on earth, and yes, our clothes will fit! Considering the variety of shapes and sizes in the United States alone, the idea is really a fantasy.

- One standard guarantees that some of the population will not have any clothes that fit. One could argue this situation exists today, so why not try one standard. With no allowance to adapt to fit the wide range of shapes and sizes, then outliers will never have clothes that fit.

- Our population is constantly changing. The most recent sizing study revealed that we are taller and weigh more than we did in the past. One standard would quickly become outdated.

- Sizing studies are very expensive and labor intensive. Studies are not done frequently, so manufacturers will always be behind what is happening in the real world.

Loosely conforming to a standard while yet adapting to meet a customer's need.

Even if one standard to rule them all is unrealistic, we still need a standard. ASTM and the latest Sizing USA study have provided us with a standard that any manufacturer can use (for a price, of course). These measurement and sizing specs can act as a guide, a place to start. As a manufacturer develops their customer profile, they can adapt these standards to meet the needs of their customer.

Over the years, it's important to compare your product against these standards. I've seen patterns and sizing drift from these standards naturally through errors. These errors are not intentional, they just happen and can easily pass from one style to the next. So a careful study and comparison can bring things back. This includes measuring fit models and comparing them against the standard and analyzing customer returns due to fit issues.

In-house size standardization

Once a sizing standard is established for a brand, it is important to adhere to that standard during product development. As an example, all new pants styles have the same finished length and waist sizes as specified. Variations in fit can come from multiple sources due to fabric variations (or problems), construction issues (taking too big/small a seam allowance, cutting errors), or variations in a pattern. You have to be careful not to draft a pattern from scratch every time. Pattern makers in the industry will use the patterns from an already proven style to develop the new style. This practice ensures consistent fit across styles. A quality control process through each step of development and production is necessary to find problems before they become big ones.

A few words on vanity sizing

Vanity sizing implies that a manufacturer wilfully chooses to ignore a size standard and relabel a size smaller than it actually is. I do not believe there is a vast conspiracy to do this intentionally. Instead I think manufacturers are trying to meet the needs of their customers while trying to conform to a standard.

*This blog entry was inspired from my reading in the book Sizing in Clothing and more specifically the article Sizing Standardization by K. L. LaBat. I made very few notes on this article and don't remember much of what I read. I did make a note that LaBat tried to prove the existence of vanity sizing by studying children's age-based sizing. I thought the argument was rather weak.

January 27, 2015

Creating sizing systems for clothing

This is a continuation of my review of Sizing in Clothing. The previous blog entries are History of Sizing, and the Book Review.

What does it take to create a sizing system? We often taken for granted a size chart on a retail website or print catalog. And when something doesn't fit, it's easy to blame the size system used by the manufacturer. And we've all been there. Shopping for blue jeans or a swimsuit causes a lot of anxiety and stress as we go through more than one size to find something that fits. A. Petrova discussed all of the variables that go into making those size charts that help you select the right size in the article Creating Sizing Systems found in the Sizing in Clothing book.

So what does it take? The first big step is to measure a population and then to divide that population into various body shapes such as Misses, Petites, Tall, Plus, etc. Each category is defined by certain control dimensions such as height, weight, waist, chest, hips, or whatever is considered the key dimensions. Usually there are 3-4 key body measurements. These kind of measurement studies are expensive and are usually undertaken by government, universities, and trade organizations.

Next, each category is subdivided into sizes contained within a size range. Each category is labelled a size designation. It could be Small-Medium-Large, or numbers such as 2, 4, 6, 8, 10. These size labels are meaningless until associated with a set of body measurements. (We could get into a discussion of vanity sizing here but it really doesn't matter what you call a size. It's the underlying body measurements that are key). In the US, we are accustomed to knowing what size to start with when shopping without knowing our body measurements. In the EU, there are similar difficulties though there has been some push to adopt the centilong system. This system identifies a size by height with some corresponding girth measurements. Not all European manufacturers have done this and some are as inconsistent in application as their American counterparts.

A. Petrova continues the article with some ideas on how to develop size systems or charts based on garment styles versus just body measurements. The biggest disadvantage to this idea is that the customer would need to know several size scales when shopping, making shopping a complicated experience. The advantage is that fit could be fine tuned, maybe.

So who is to blame when clothes don't fit? Is it the size chart? Maybe, maybe not. There are so many variables that it is hard to select just one reason. The fit model used in pattern development may match the size chart, but not be representative of the consumer. In other words there could be a mismatch between expectations and reality between the manufacturer and the customer. Grade rules may not match or equal actual body grades - which is a discussion for another article. Perhaps the size chart information was incomplete, lacked sufficient instruction, or had a typo. Poor construction or poor fabric quality play a factor. When analyzing sales information and returns, all of these things have to be considered.

|

| By Downtowngal (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

So what does it take? The first big step is to measure a population and then to divide that population into various body shapes such as Misses, Petites, Tall, Plus, etc. Each category is defined by certain control dimensions such as height, weight, waist, chest, hips, or whatever is considered the key dimensions. Usually there are 3-4 key body measurements. These kind of measurement studies are expensive and are usually undertaken by government, universities, and trade organizations.

Next, each category is subdivided into sizes contained within a size range. Each category is labelled a size designation. It could be Small-Medium-Large, or numbers such as 2, 4, 6, 8, 10. These size labels are meaningless until associated with a set of body measurements. (We could get into a discussion of vanity sizing here but it really doesn't matter what you call a size. It's the underlying body measurements that are key). In the US, we are accustomed to knowing what size to start with when shopping without knowing our body measurements. In the EU, there are similar difficulties though there has been some push to adopt the centilong system. This system identifies a size by height with some corresponding girth measurements. Not all European manufacturers have done this and some are as inconsistent in application as their American counterparts.

A. Petrova continues the article with some ideas on how to develop size systems or charts based on garment styles versus just body measurements. The biggest disadvantage to this idea is that the customer would need to know several size scales when shopping, making shopping a complicated experience. The advantage is that fit could be fine tuned, maybe.

So who is to blame when clothes don't fit? Is it the size chart? Maybe, maybe not. There are so many variables that it is hard to select just one reason. The fit model used in pattern development may match the size chart, but not be representative of the consumer. In other words there could be a mismatch between expectations and reality between the manufacturer and the customer. Grade rules may not match or equal actual body grades - which is a discussion for another article. Perhaps the size chart information was incomplete, lacked sufficient instruction, or had a typo. Poor construction or poor fabric quality play a factor. When analyzing sales information and returns, all of these things have to be considered.

January 20, 2015

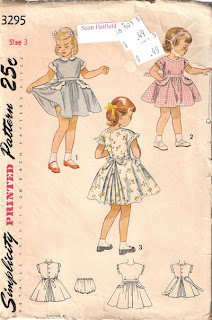

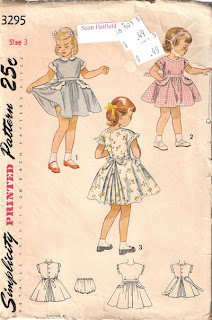

Relying on old body measurements and pattern drafting instructions

There is a certain bit of nostalgia when looking back in time. We often say, "They don't build things like they used to," implying that we paid closer attention to quality and details. This same kind of thinking is also found in pattern making and sewing. There is a general assumption that the way things were done in the past are better then they are now. Some pull out old measurement charts and drafting instructions to recreate the past for a better present. We don't even have to go very far. There is the hope of a stylish outfit made of a 1950's sewing pattern and thinking that it will fit.

Before I go any further, let me say there is nothing wrong with looking backward and trying to understand how things were done. It is a fun exercise to draft a pattern using old instructions or sewing up that vintage pattern. This is about using old body measurement data and pattern drafting instructions to create modern clothing.

There are some key factors that make up a size - height, weight, girth, and shape. I suppose in the 1890s pattern makers and tailors were just beginning to understand the relationships between each of those factors. At least for men's clothing. Women's clothing was still a guessing game requiring customized fit. It wasn't until the 1940s that we began to see the connection to height, weight, and girth. Statistical analysis could finally show that when one factor changes, the others do as well. The studies done by Ruth O'Brien and her committee allowed us to see and understand body proportions and shapes and use that information to predict overall size. This information was not truly implemented until the 1950s and 1960s. Other studies have come along to add to our knowledge. A study in the early 1970s expanded our knowledge of children's body measurements. Another study, SizeUSA, was released in 2004 and greatly enhanced our knowledge of the US population using 3D body scanners.*

If you draft a pattern using older drafting instructions and body measurement charts, you will create something that is based on that time's understanding of body proportions and measurements. If that is your goal, then all is well and good. But if you find a free measurement chart dating back even 50 years, then you are placing your product in the 1950s.

We know this because not only has our understanding of anthropometry increased, but we know that the body measurements of a population change over time. If you are interested in creating your own line, it is in your best interest to obtain the most recent (and reliable) measurement data you can.

*Unfortunately the SizeUSA data is held behind a very expensive lock and key. Access is only available to those willing to pay a pretty hefty sum despite the study receiving tax dollars. Some ASTM body measurement charts have been updated to incorporate the study data. The ASTM children's body measurement chart is a mash-up of data that incorporates multiple studies dating back to Ruth O'Brien's 1941 study and some more modern data.

January 08, 2015

The history of standardized sizes for clothing

Do you ever wonder how people came up with the idea of sizing clothes? The creation of sizes allowed for the mass production of ready-to-wear garments. It was not created at a meeting of industry professionals, but evolved over time. Great leaps in sizing occurred because of war - somebody had to quickly and efficiently outfit an army.

Winifred Aldrich traces the development of sizes and ready to wear in her article History of Sizing and Ready-to-Wear Garments found in the Sizing in Clothing book*. Aldrich is a British pattern maker, designer, and researcher. I own two of her pattern drafting manuals and consider them among the best drafting manuals available (link in the sidebar to the left for the children's drafting manual). She knows her stuff, and she presents it well.

book*. Aldrich is a British pattern maker, designer, and researcher. I own two of her pattern drafting manuals and consider them among the best drafting manuals available (link in the sidebar to the left for the children's drafting manual). She knows her stuff, and she presents it well.

The understanding of body proportions began slowly with tailors producing clothing for men. They used strips of paper to measure the body and transfer the measurements to cloth. In time tailors devised tape measures and drafting systems. A size was not the beginning of the drafting job, rather the completed garment represented the size of the customer. As the industrial revolution progressed, tailors began to teach and sell their drafting systems. This included some already drafted patterns, sometimes in more than one size.

The concept was revolutionary and men began to be able to purchase their clothing ready made. Women, on the other hand, still had most of their clothing custom made into the early 20th century. There were attempts at creating patterns for women with named sizes, but it still required customization. There was a lack of knowledge of women's body measurements most likely because of the Victorian ideals of the time.

It is important to understand that our understanding of body measurements and proportions were not formalized until the 1940's. Ruth O'Brien, an employee of the U.S. Department of Home Economics and the Department of Agriculture, was commissioned to conduct a body measurement study of the American population. The purpose was to create a set of size standards based on reliable data that the apparel industry could use. The work involved in this study was enormous and revolutionary. O'Brien and her department created a measurement procedure that is still in existence today (only to be superseded by 3D body scanning). The data from these studies have been study and analyzed around the world.

To put this in perspective, it wasn't until the 1940s that we could finally see and understand human proportions with any clarity. It's easy to pan this early work as outdated and wrong but the 1940's was not that long ago. We still have so much to learn and understand.

A fun little factoid. Grading using the shifting or slide method, a common method still used today, can be traced back to 1908.

Aldrich's article goes into much more depth about the history of sizing. She includes pictures of early patterns and sizing systems. It is well worth a read if you can get a copy of it. This article is a combination and expansion of two previously written articles found in the journal Textile History.

*As I review individual articles from the Sizing in clothing book, I will not give a detailed discussion of each article. Rather, I will summarize and highlight a few key points along with my own thoughts on the subject.

Winifred Aldrich traces the development of sizes and ready to wear in her article History of Sizing and Ready-to-Wear Garments found in the Sizing in Clothing

The understanding of body proportions began slowly with tailors producing clothing for men. They used strips of paper to measure the body and transfer the measurements to cloth. In time tailors devised tape measures and drafting systems. A size was not the beginning of the drafting job, rather the completed garment represented the size of the customer. As the industrial revolution progressed, tailors began to teach and sell their drafting systems. This included some already drafted patterns, sometimes in more than one size.

The concept was revolutionary and men began to be able to purchase their clothing ready made. Women, on the other hand, still had most of their clothing custom made into the early 20th century. There were attempts at creating patterns for women with named sizes, but it still required customization. There was a lack of knowledge of women's body measurements most likely because of the Victorian ideals of the time.

It is important to understand that our understanding of body measurements and proportions were not formalized until the 1940's. Ruth O'Brien, an employee of the U.S. Department of Home Economics and the Department of Agriculture, was commissioned to conduct a body measurement study of the American population. The purpose was to create a set of size standards based on reliable data that the apparel industry could use. The work involved in this study was enormous and revolutionary. O'Brien and her department created a measurement procedure that is still in existence today (only to be superseded by 3D body scanning). The data from these studies have been study and analyzed around the world.

To put this in perspective, it wasn't until the 1940s that we could finally see and understand human proportions with any clarity. It's easy to pan this early work as outdated and wrong but the 1940's was not that long ago. We still have so much to learn and understand.

A fun little factoid. Grading using the shifting or slide method, a common method still used today, can be traced back to 1908.

Aldrich's article goes into much more depth about the history of sizing. She includes pictures of early patterns and sizing systems. It is well worth a read if you can get a copy of it. This article is a combination and expansion of two previously written articles found in the journal Textile History.

*As I review individual articles from the Sizing in clothing book, I will not give a detailed discussion of each article. Rather, I will summarize and highlight a few key points along with my own thoughts on the subject.

December 20, 2010

Tutorial: Reduce or Remove Sleeve Cap Ease pt. 2

I received a really great question on my previous tutorial on how to remove or reduce sleeve cap ease. Gina's question deserves it's own blog post.

If you are working with a commercial pattern for adults, the approach will be similar. You can't always reduce the bicep line and the overall changes may be quite significant. Patterns from the Big 4 notoriously have too much sleeve cap ease. To be fair, if you follow the drafting instructions in some pattern drafting books, you end up adding in a fair amount of ease too. One pattern making book has instructions that result in as much as 1.5 inches of ease in a set-in toddler sleeve. Way too much. Such a practice is not common in the fashion industry and the production sewers will refuse to set-in the sleeves.

I had difficulty coming up with a solution and so I had to ask my pattern making friends at the Fashion Incubator Forum. We have to assume that everything fits Gina as it should, though it's possible there is some other fit issue that is contributing to the bicep width problem to begin with.(1) There are two possible solutions and neither is quick nor easy. Both will require testing. To add bicep width, slash and spread or slash and pivot the sleeve to the desired measurement. This alteration will require fixing the sleeve cap anyway.

1. Draft a new sleeve from scratch. (My solution)

2. Reduce the sleeve cap height equal to the amount of ease to be removed. (From Nora of the Fashion Incubator Forum).

Sometimes it's just easier to start over. It may save time in the long run and you will get exactly the sleeve you want.

If you would rather fix the sleeve, you can try Nora's suggestion. Nora's suggestion leaves the bicep width alone and only adjusts the sleeve cap height.

1. Begin by walking the sleeve along the armhole in a similar manner to my previous tutorial. In this case, start at the bottom and walk the armhole toward the shoulder. You will need to walk the sleeve on both the front and back armholes matching up the front of the sleeve with the front bodice and the back bodice with the back sleeve. Your sleeve should not be symmetrical and you will need to check the entire armhole. As you work, you may want to check the entire armhole and sleeve cap.

2. Measure from the seam line of the shoulder on the bodice to the center notch of the sleeve. This will be equal to the amount of ease on one side of your sleeve. Repeat for the back armhole. Total up the ease for the front and the back of the sleeve. This will equal the total sleeve cap ease.

3. Reduce the sleeve cap height equal to the amount of ease that needs to be removed and redraw the sleeve cap. You will need to repeat these steps until you get exactly the amount of ease needed to set the sleeve and no more.

Neither Nora nor I can guarantee that this method is the answer. This method will require lots of back and forth testing and iteration. The method is similar enough to my previous tutorial that I think it will work eventually. If you have the patience for lots of testing, then go for it. Also remember that you may still need *some* ease. When we say zero ease, we don't really mean zero ease. You may need some to help set the sleeve in. The only way to know is to sew up a few samples. 1/4" to 1/2" of total ease is not unusual. This ease is required to help sew opposing curves together. The sleeve should be against the feed dogs as it moves under the foot and the action of the feed dogs may require a little bit of ease so that the sleeve cap and armscye meet up in the end.

1. The armhole could be too small or too big. It may be in the wrong location or scooped wrong under the arms.

Thanks to Nora for her suggestion.

Well, what do you do if you have big arms but too much ease? If I move it over I will lose bicep room. I am working with a dress right now and everything fits but the sleeves are tight and the have too much ease. How do I widen the sleeve get rid of ease and fit it to the armhole?This is a really great question and may require me to consider re-writing my tutorial. My previous tutorial is based off my experience drafting patterns for children's clothing. Usually it is not a problem to reduce the bicep line because it's usually too big anyway. My overall changes are small because I am perfecting patterns that I have drafted myself.

Thanks

If you are working with a commercial pattern for adults, the approach will be similar. You can't always reduce the bicep line and the overall changes may be quite significant. Patterns from the Big 4 notoriously have too much sleeve cap ease. To be fair, if you follow the drafting instructions in some pattern drafting books, you end up adding in a fair amount of ease too. One pattern making book has instructions that result in as much as 1.5 inches of ease in a set-in toddler sleeve. Way too much. Such a practice is not common in the fashion industry and the production sewers will refuse to set-in the sleeves.

I had difficulty coming up with a solution and so I had to ask my pattern making friends at the Fashion Incubator Forum. We have to assume that everything fits Gina as it should, though it's possible there is some other fit issue that is contributing to the bicep width problem to begin with.(1) There are two possible solutions and neither is quick nor easy. Both will require testing. To add bicep width, slash and spread or slash and pivot the sleeve to the desired measurement. This alteration will require fixing the sleeve cap anyway.

1. Draft a new sleeve from scratch. (My solution)

2. Reduce the sleeve cap height equal to the amount of ease to be removed. (From Nora of the Fashion Incubator Forum).

Sometimes it's just easier to start over. It may save time in the long run and you will get exactly the sleeve you want.

If you would rather fix the sleeve, you can try Nora's suggestion. Nora's suggestion leaves the bicep width alone and only adjusts the sleeve cap height.

1. Begin by walking the sleeve along the armhole in a similar manner to my previous tutorial. In this case, start at the bottom and walk the armhole toward the shoulder. You will need to walk the sleeve on both the front and back armholes matching up the front of the sleeve with the front bodice and the back bodice with the back sleeve. Your sleeve should not be symmetrical and you will need to check the entire armhole. As you work, you may want to check the entire armhole and sleeve cap.

2. Measure from the seam line of the shoulder on the bodice to the center notch of the sleeve. This will be equal to the amount of ease on one side of your sleeve. Repeat for the back armhole. Total up the ease for the front and the back of the sleeve. This will equal the total sleeve cap ease.

3. Reduce the sleeve cap height equal to the amount of ease that needs to be removed and redraw the sleeve cap. You will need to repeat these steps until you get exactly the amount of ease needed to set the sleeve and no more.

Neither Nora nor I can guarantee that this method is the answer. This method will require lots of back and forth testing and iteration. The method is similar enough to my previous tutorial that I think it will work eventually. If you have the patience for lots of testing, then go for it. Also remember that you may still need *some* ease. When we say zero ease, we don't really mean zero ease. You may need some to help set the sleeve in. The only way to know is to sew up a few samples. 1/4" to 1/2" of total ease is not unusual. This ease is required to help sew opposing curves together. The sleeve should be against the feed dogs as it moves under the foot and the action of the feed dogs may require a little bit of ease so that the sleeve cap and armscye meet up in the end.

1. The armhole could be too small or too big. It may be in the wrong location or scooped wrong under the arms.

Thanks to Nora for her suggestion.

August 31, 2009

Comparing pattern shaping and children's sizes follow-up

Kathleen suggested that I post an update on a previous grading post I did about a year ago. You can read what I wrote previously at When Patterns Collide. In that post I suggested that it would be possible to combine the 24M and 2T and the 4T and the 4. My reasoning being that the 24M and the 2T are essentially the same sizes - why differentiate them? The subject is a little complex and perhaps controversial - at least to pattern making geeks. My goal was to reduce the work load. I was drafting and grading all of my patterns by hand. I am incredibly slow grading by hand. In addition, I was trying to solve one particular sizing problem that shows up in childrenswear, that is hard to illustrate. Since I shut down my Prairie Roses line, I am not knee deep in pattern making as I was a year ago. But perhaps it may be helpful to explain what I ended up doing.

Originally, I broke up my sizes into these ranges:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M, 24M - sample size 12M

2T, 3T, 4T - sample size 3T

4, 5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

These ranges are rather typical of what you will find in retail stores. When developing my patterns, I have to make and grade the patterns for each size range separately. You cannot make one set of patterns in one size and grade them up and down all the way. It won't work because that many sizes will cause minute grading errors and strange fit, especially on the smallest and largest sizes. As you define your grading and size measurements, you will find that the 24M and 2T and the 4T and 4 overlap. I followed the Jack Handford grading rules, which are pretty darn good, but end up with a result like this:

Originally, I broke up my sizes into these ranges:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M, 24M - sample size 12M

2T, 3T, 4T - sample size 3T

4, 5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

These ranges are rather typical of what you will find in retail stores. When developing my patterns, I have to make and grade the patterns for each size range separately. You cannot make one set of patterns in one size and grade them up and down all the way. It won't work because that many sizes will cause minute grading errors and strange fit, especially on the smallest and largest sizes. As you define your grading and size measurements, you will find that the 24M and 2T and the 4T and 4 overlap. I followed the Jack Handford grading rules, which are pretty darn good, but end up with a result like this:

In the picture above, the size 4 is laying on top of the size 4T. The size 4T is actually too long in length and too wide. I double checked all of my grading and there was no mistake. The size 4T was graded off my 3T and the size 4 off of the 5. The shaping of the sample size pattern pieces varied a little. The toddler was a little boxier because toddlers don't have any waist shaping, whereas a 5 year old does. If I were to leave my patterns this way, someone will eventually hang the two sizes next to each other and think there was some kind of manufacturing mistake. I needed to fix my patterns so that each size is incrementally bigger.

To do this, I rearranged my size ranges, combining some sizes:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M - sample size 12M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4 - sample size 3T

5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

The next thing I did was reworked the shaping of my toddler sizes to look more like the 4-6x range. I pulled the waist in some and made the armhole smaller. I made these shaping changes because I found that my toddler patterns were just a little too big. Now, I can lay all of my bodice pattern pieces in order and they get incrementally larger from the 3M to the 6x. Your patterns may look different, but it is worth comparing the sizes on the outside edges of your ranges to make sure you don't have something weird show up like I did.

Even though I combined some sizes, I kept this behind the scenes. My customers still saw all of the sizes separated out. If someone ordered a size 24M and another ordered a 2T, the dress would be exactly the same except for the size tag. I offered all of the sizes on my website so that customers would see something familiar. Perhaps it seems a little dishonest? I don't think so because in the real world a 24M child is the same size as a 2T and I was willing to take the chance. For what its worth, no one ever complained or returned those sizes for fit issues.

Now, I don't know that what I did is "the way it should be done". In the past though, I have had people question why the 24M was larger than the 2T and I had no explanation. Once I worked through grading all of my patterns by hand, it started to click in my head. The relationship of the shape of the pattern pieces, the grade, and body measurements are all connected.

To do this, I rearranged my size ranges, combining some sizes:

3M, 6M, 9M, 12M, 18M - sample size 12M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4 - sample size 3T

5, 6, 6x - sample size 5

The next thing I did was reworked the shaping of my toddler sizes to look more like the 4-6x range. I pulled the waist in some and made the armhole smaller. I made these shaping changes because I found that my toddler patterns were just a little too big. Now, I can lay all of my bodice pattern pieces in order and they get incrementally larger from the 3M to the 6x. Your patterns may look different, but it is worth comparing the sizes on the outside edges of your ranges to make sure you don't have something weird show up like I did.

Even though I combined some sizes, I kept this behind the scenes. My customers still saw all of the sizes separated out. If someone ordered a size 24M and another ordered a 2T, the dress would be exactly the same except for the size tag. I offered all of the sizes on my website so that customers would see something familiar. Perhaps it seems a little dishonest? I don't think so because in the real world a 24M child is the same size as a 2T and I was willing to take the chance. For what its worth, no one ever complained or returned those sizes for fit issues.

Now, I don't know that what I did is "the way it should be done". In the past though, I have had people question why the 24M was larger than the 2T and I had no explanation. Once I worked through grading all of my patterns by hand, it started to click in my head. The relationship of the shape of the pattern pieces, the grade, and body measurements are all connected.

February 04, 2009

Who creates grade rules?

Some one asked me a grading question the other day. She wanted to know who creates grade rules?

A pattern maker, grader, or you could make the grade rules. If you choose to make the grade rules yourself, I have some guides available in The Organized Fashion Designer and The Simple Tech Pack. It's harder with children's clothing because there isn't as much standardization. An experienced grader should have some standard charts or be able to develop rules off of your measurement charts. I would personally start developing grade rules by referencing the Jack Handford book and make modifications as needed. I would only let a pattern maker or grader do it who has experience with it.

You can buy measurement charts from ASTM as a place to start. The ASTM measurement charts for children are probably the best resource for children's body measurements. Be cautious of using free charts found on the Internet. I have seen free measurement charts on the Internet riddled with inconsistencies that could lead to serious errors.

If you have time, you may want to sew up the smallest and largest sizes just to double check the grade and sizing. It doesn't have to be in your production fabric or anything. A fitting is the only way to know if your grade is correct. You won't need to do this on every style or very often. Kind of important when starting out though.

Labels:

ASTM,

Grade rules,

Grading,

Measurement charts,

Patternmaking,

References,

Size Charts,

Sizing

January 09, 2008

Grading Pants Notes pt. 2

The following are my notes on grading infant-toddler pants. Having a copy of the Jack Handford grading manual will be helpful in understanding what these notes mean. Hopefully you have at least read the introduction and the instructions for grading a bodice. If you don't have a copy of the book, save these notes anyway - they may come in handy. This is part 2 of the series. Part 1 contains an explanation of direction arrows.

This will be a short entry and only partially about grading pants. Mostly it is about Handford's notation and what caused me confusion.

In this drawing I superimposed the direction arrows onto a bodice pattern. There is a similar drawing in Handford's book, page 6 and in Kathleen Fasanella's book, pg 174. All movements start from your point of origin which I have indicated in my drawing. Depending on how you set-up your grading, it will be helpful to draw direction arrows on your patterns.

In this drawing I superimposed the direction arrows onto a bodice pattern. There is a similar drawing in Handford's book, page 6 and in Kathleen Fasanella's book, pg 174. All movements start from your point of origin which I have indicated in my drawing. Depending on how you set-up your grading, it will be helpful to draw direction arrows on your patterns.

Now notice the little black triangle under the point of origin. Handford uses this triangle in many drawings. I interpreted those triangles to mean the "point of origin" and that is where I messed up.

Compare the drawings for pants of women (pg 77), men (188-189), and children (219). You'll notice that Handford adds or drops those black triangles almost randomly. Some drawings have them, some don't.

The black triangles don't indicate "point of origin". Instead, I think Handford is borrowing the notation from geometry where it means "right angle". Your direction arrows should be perpendicular - at 90 degrees. If you look at the pants drafts (sorry no more drawings for today), you can see his direction arrows are drawn down the center of the pant legs with two black triangles - meaning the lines should all be perpendicular. In my head, I was seeing "point of origin" or (0,0) on an X-Y coordinate plane. Interpreting things this way caused me to move my pattern pieces incorrectly (my own dumb fault for trying to over analyze things).

Anyway, by nesting my pieces I found my error and realized Handford's direction arrows do not always show the point of origin on all of his drawings. They just show direction.

Clear as mud?

This will be a short entry and only partially about grading pants. Mostly it is about Handford's notation and what caused me confusion.

In this drawing I superimposed the direction arrows onto a bodice pattern. There is a similar drawing in Handford's book, page 6 and in Kathleen Fasanella's book, pg 174. All movements start from your point of origin which I have indicated in my drawing. Depending on how you set-up your grading, it will be helpful to draw direction arrows on your patterns.

In this drawing I superimposed the direction arrows onto a bodice pattern. There is a similar drawing in Handford's book, page 6 and in Kathleen Fasanella's book, pg 174. All movements start from your point of origin which I have indicated in my drawing. Depending on how you set-up your grading, it will be helpful to draw direction arrows on your patterns.Now notice the little black triangle under the point of origin. Handford uses this triangle in many drawings. I interpreted those triangles to mean the "point of origin" and that is where I messed up.

Compare the drawings for pants of women (pg 77), men (188-189), and children (219). You'll notice that Handford adds or drops those black triangles almost randomly. Some drawings have them, some don't.

The black triangles don't indicate "point of origin". Instead, I think Handford is borrowing the notation from geometry where it means "right angle". Your direction arrows should be perpendicular - at 90 degrees. If you look at the pants drafts (sorry no more drawings for today), you can see his direction arrows are drawn down the center of the pant legs with two black triangles - meaning the lines should all be perpendicular. In my head, I was seeing "point of origin" or (0,0) on an X-Y coordinate plane. Interpreting things this way caused me to move my pattern pieces incorrectly (my own dumb fault for trying to over analyze things).

Anyway, by nesting my pieces I found my error and realized Handford's direction arrows do not always show the point of origin on all of his drawings. They just show direction.

Clear as mud?

Labels:

Directions,

Grading,

Manufacturing,

Measurement charts,

Notation,

Patternmaking,

Sizing

January 03, 2008

Grading Pants Notes pt. 1

The following are my notes on grading infant-toddler pants. Having a copy of the Jack Handford grading manual will be helpful in understanding what these notes mean. Hopefully you have at least read the introduction and the instructions for grading a bodice. If you don't have a copy of the book, save these notes anyway - they may come in handy.

These are the first of my notes on grading pants using the Jack Handford book. Part one of these notes is an explanation about directions and movements of the pattern pieces. Later I will talk specifically about grading pants, shorts, and what I think is a mistake in the children's chapter. Handford's book is a textbook and like most design text books he starts with grading women's styles. The book progresses from woman's bodices, pants, and skirts, to men's styles, and finally to children. When design/pattern making/grading book authors finally get to the children's info, the information becomes abbreviated and incomplete (if they include it at all). Handford's book is different because he does include infant and toddler information and it is more complete than any other grading manual out there. Still, he falls into the same trap. He assumes the student has worked through all of the previous chapters before arriving at the children's chapter. He assumes you have a strong grading background and understand his method completely. But what about those who have no interest in grading woman's clothing and skip ahead to the chapters with the most relevant information? This is what I did.

Now I do have a strong grading background - computer grading. Hand and computer grading are similar and Handford's method is how it is done in the industry. The direction of the grading is done in a similar fashion. The grade rules are similar. The grade steps are the same. But physically moving a hard, paper pattern around versus selecting points and entering relative coordinates is different. Despite that, I have a general sense of how a pattern should grow or shrink between sizes - and that helped me finally understand Handford's method better.

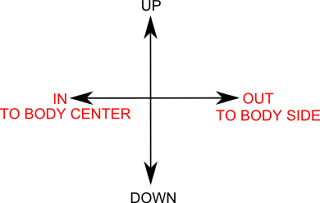

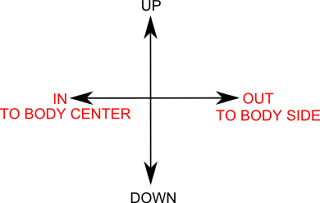

To start out, you will need to compare the grade instructions for women's pants to children. If you turn to page 79 (grading of women's back pant), you will notice arrows with words around each pattern piece. The arrows look like this drawing. If you flip over to the toddler pant grade (page 225), you will see arrows, but no words. It is at this point that Handford assumes you will know what direction is In, Out, Up, or Down. Now study the drawings of the women's pant and the children's pant. Do you see any other differences? There is one major difference that threw me off - I'll explain later...

To start out, you will need to compare the grade instructions for women's pants to children. If you turn to page 79 (grading of women's back pant), you will notice arrows with words around each pattern piece. The arrows look like this drawing. If you flip over to the toddler pant grade (page 225), you will see arrows, but no words. It is at this point that Handford assumes you will know what direction is In, Out, Up, or Down. Now study the drawings of the women's pant and the children's pant. Do you see any other differences? There is one major difference that threw me off - I'll explain later...

The next thing to understand are directions. All patterns will move IN, OUT, UP, or DOWN. Handford shows how this works on page 6 in relation to a bodice. The children's chapter doesn't have these extra helps. So I drew arrows like on the right and below to help remind me of grading direction. I added the words to body center or to body side to remind me of how to move the pattern IN or OUT. As you can see, IN or OUT can change depending on whether you are grading a left or right piece (applies to front or back too). Directions may change again when grading darts. Be sure to study styles with darts to see the changes. Infant-Toddler styles do not have darts, so movements will occur like these drawings. Movements UP move toward the body head and DOWN toward the feet. UP and DOWN movements are always the same.

The next thing to understand are directions. All patterns will move IN, OUT, UP, or DOWN. Handford shows how this works on page 6 in relation to a bodice. The children's chapter doesn't have these extra helps. So I drew arrows like on the right and below to help remind me of grading direction. I added the words to body center or to body side to remind me of how to move the pattern IN or OUT. As you can see, IN or OUT can change depending on whether you are grading a left or right piece (applies to front or back too). Directions may change again when grading darts. Be sure to study styles with darts to see the changes. Infant-Toddler styles do not have darts, so movements will occur like these drawings. Movements UP move toward the body head and DOWN toward the feet. UP and DOWN movements are always the same.

I hope I haven't thoroughly confused anyone yet. I felt like this brief explanation of the notation and movements was necessary before getting into more detail.

I hope I haven't thoroughly confused anyone yet. I felt like this brief explanation of the notation and movements was necessary before getting into more detail.

If you have questions, please leave them in comments.

These are the first of my notes on grading pants using the Jack Handford book. Part one of these notes is an explanation about directions and movements of the pattern pieces. Later I will talk specifically about grading pants, shorts, and what I think is a mistake in the children's chapter. Handford's book is a textbook and like most design text books he starts with grading women's styles. The book progresses from woman's bodices, pants, and skirts, to men's styles, and finally to children. When design/pattern making/grading book authors finally get to the children's info, the information becomes abbreviated and incomplete (if they include it at all). Handford's book is different because he does include infant and toddler information and it is more complete than any other grading manual out there. Still, he falls into the same trap. He assumes the student has worked through all of the previous chapters before arriving at the children's chapter. He assumes you have a strong grading background and understand his method completely. But what about those who have no interest in grading woman's clothing and skip ahead to the chapters with the most relevant information? This is what I did.

Now I do have a strong grading background - computer grading. Hand and computer grading are similar and Handford's method is how it is done in the industry. The direction of the grading is done in a similar fashion. The grade rules are similar. The grade steps are the same. But physically moving a hard, paper pattern around versus selecting points and entering relative coordinates is different. Despite that, I have a general sense of how a pattern should grow or shrink between sizes - and that helped me finally understand Handford's method better.

To start out, you will need to compare the grade instructions for women's pants to children. If you turn to page 79 (grading of women's back pant), you will notice arrows with words around each pattern piece. The arrows look like this drawing. If you flip over to the toddler pant grade (page 225), you will see arrows, but no words. It is at this point that Handford assumes you will know what direction is In, Out, Up, or Down. Now study the drawings of the women's pant and the children's pant. Do you see any other differences? There is one major difference that threw me off - I'll explain later...

To start out, you will need to compare the grade instructions for women's pants to children. If you turn to page 79 (grading of women's back pant), you will notice arrows with words around each pattern piece. The arrows look like this drawing. If you flip over to the toddler pant grade (page 225), you will see arrows, but no words. It is at this point that Handford assumes you will know what direction is In, Out, Up, or Down. Now study the drawings of the women's pant and the children's pant. Do you see any other differences? There is one major difference that threw me off - I'll explain later... The next thing to understand are directions. All patterns will move IN, OUT, UP, or DOWN. Handford shows how this works on page 6 in relation to a bodice. The children's chapter doesn't have these extra helps. So I drew arrows like on the right and below to help remind me of grading direction. I added the words to body center or to body side to remind me of how to move the pattern IN or OUT. As you can see, IN or OUT can change depending on whether you are grading a left or right piece (applies to front or back too). Directions may change again when grading darts. Be sure to study styles with darts to see the changes. Infant-Toddler styles do not have darts, so movements will occur like these drawings. Movements UP move toward the body head and DOWN toward the feet. UP and DOWN movements are always the same.

The next thing to understand are directions. All patterns will move IN, OUT, UP, or DOWN. Handford shows how this works on page 6 in relation to a bodice. The children's chapter doesn't have these extra helps. So I drew arrows like on the right and below to help remind me of grading direction. I added the words to body center or to body side to remind me of how to move the pattern IN or OUT. As you can see, IN or OUT can change depending on whether you are grading a left or right piece (applies to front or back too). Directions may change again when grading darts. Be sure to study styles with darts to see the changes. Infant-Toddler styles do not have darts, so movements will occur like these drawings. Movements UP move toward the body head and DOWN toward the feet. UP and DOWN movements are always the same. I hope I haven't thoroughly confused anyone yet. I felt like this brief explanation of the notation and movements was necessary before getting into more detail.

I hope I haven't thoroughly confused anyone yet. I felt like this brief explanation of the notation and movements was necessary before getting into more detail.If you have questions, please leave them in comments.

November 29, 2007

Aldrich vs. Armstrong pattern drafting books

The two most useful (IMO) books for children's pattern making are by Winifred Aldrich

From Tiki:

I've been doing the same, pouring over measuring charts and re-working patterns. My 4 y.o. is my fit model, though, so I do have the luxury (ha!) of dressing her up when I need a fit, but it's by no means easier than having a dress form that won't want to dance around the room while I'm trying to check the fit.If you draft your own versions from each method, I would be interested in hearing your comments. I agree with a lot of what Tiki has said about the ease of drafting Aldrich over Armstrong. Though I prefer Armstrong for some things. I am fairly certain that Aldrich created all of the drafts in her book. I think the points of reference are unique to each draft and can't be used for comparison between drafts. It may make things simpler if they were consistent. Also some of the differences may come down to European vs. American fit and expectations. Europeans tend to fit closer to the body - Americans have a boxier fit.

Thank you so much for your explanation below about the flat patterns. I meant to respond earlier, but then got caught up in the holiday madness. Anyway, after much pondering conceptually over the "right" pattern method, I was encouraged by your explanation, especially that it's the fit that matters, not so much the method for getting there. I know that probably sounds simple and obvious, but since I have no formal patternmaking training, everything is a learning experience and I sometimes get stymied because I want to do everything "right." So I finally put pencil to paper to draft Aldrich's and Armstrong's patterns and compare them to mine. My patterns are a more like Aldrich's classic, although my armhole shape isn't quite as cut out (so my armhole is somewhat in between her flat and classic). I think the shoulder width on her flat block is too wide, but I guess that's part of what creates a boxier fit versus the slimmer fit of her classic block.

I did notice that Aldrich seems to modify the front armhole and lowers the front shoulder slope even in her "flat" blocks for wovens (on the infant woven on p. 25 and on the body/shirt block on p. 39), although it's not as pronounced as in her classic block (on p. 89). And when I cut out my front and back patterns for the classic block and woven flat block, the shape and contrast between the front and back of each are not that different. In other words, the difference in the armhole shape between the front of the classic and the back of the classic is very similar to the difference in the armhole shape between the front woven flat block and the back woven flat block (I laid the fronts over the backs and compared). Of course, the armhole shaping between the front classic block and the front woven flat block are significantly different, as are the back classic and back woven flat. I'm not sure exactly what that means, really, except that she seems to apply the "true" flat (meaning identical front and back except for the neckline) as you suggested to casual knit boxy styles like t-shirts (which she drafts also for older children on p. 45).