October 09, 2013

Adapting a block pattern into something else pt. 1 : Noting changes for the new style

A block pattern is a sewing pattern that has been proven. It is a pattern that has been trued, perfected and finished with seam allowances. The pattern has been sewn up and tested for fit. In other words, a block pattern just works. A block pattern becomes a part of a pattern file which can be used to make other patterns.

In the industry we rarely draft from scratch. Instead we modify existing patterns (or blocks) into something else. Some pattern making gurus talk about using slopers. Slopers are basic patterns drafted from body measurements and do not have seam allowances. Industry level pattern makers use block patterns, with seam allowances on, to make patterns for new styles*. It saves time.

It's easier than you might think to do this and this is just one example. I'm sure other pattern makers have their own procedures. My own procedures adapt to whatever it is I'm working on and whether I'm using CAD or traditional methods.

The problem:

I have this much loved cashmere sweater jacket. I snagged it off a sales rack a couple of years ago and I absolutely love the cut and fit. You know, the perfect layering piece, warm and soft for those cool days. I usually clean it by running it through the dryer using a Dryel kit. This last time was a disaster as I had left a piece of chocolate in a pocket. Chocolate ended up all over the sweater and everything else. So, I decided to run it through the hand wash cycle on my washer. That was a mistake. While the chocolate did come out, the sweater shrank. It shrunk just enough that I'm not sure I can wear it anymore. It made me very sad. And yes, I know better. I should have hand washed it.

The solution:

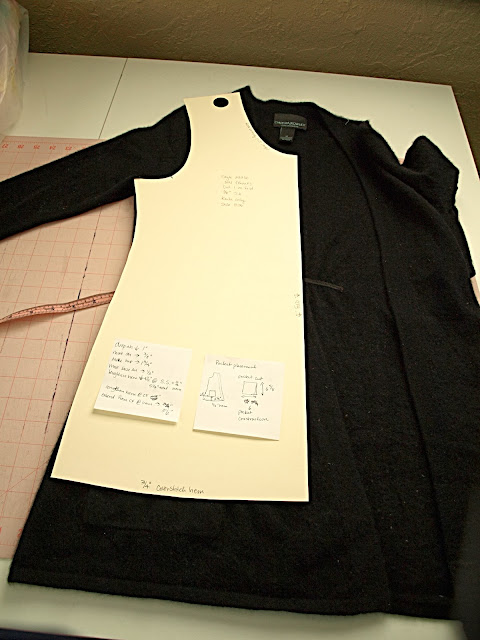

I always said that once this sweater was in pieces, I would make up a pattern to make a new one. So here it is. I recently finished up my t-shirt pattern, a block pattern ready to go. I began by carefully laying out the sweater and positioning the front t-shirt pattern on top. I then used scraps of paper to note the differences between the sweater and the pattern. You can see my notes in the picture above.

The notes** usually say something like: Move SH pt out 1/2" (left arrow) ; or Extend hem (down arrow) 3 inches. These notes are sometimes accompanied with drawings as needed. If I was working in CAD, I would just mentally note the differences and make the changes as as I went along. Since I'm drafting with pencil and paper, the notes are essential.

The next step is to trace off the t-shirt pattern and start applying the changes. More on that later.

*There are a lot of pattern making myths out there. I'm trying to keep this blog entry very focused but I'm happy to answer pattern making questions and myths in future posts. Please leave your question or comment below.

**These notes eventually find their way to my pattern piece catalog. I assign a pattern piece number, note the style/pattern piece that the new piece came from, and then tell what changes were applied and any other relevant details. Blank forms for managing patterns are available in my Pattern Making bundle or in the book with complete instructions.

September 30, 2013

A case study in paying for fabric waste

I recently had a customer bring me some fabric for some flannel blankets. She mentioned off hand that some of the fabric had not been cut very straight by the fabric store sales clerk. This is not terribly unusual - I see it all the time with my custom hemstitching customers. I've seen it with fabric that I have purchased. I don't blame the sales clerks entirely. The sales clerks have to handle (wrestle) the fabric on the bolts, try to straighten it out, and then use dull scissors to cut it. The entire set-up wastes time and gives a poor outcome nearly every time. Is it any wonder that the industry prefers fabric on rolls? This is one reason I always buy a bit more yardage.

This particular case was fairly egregious. My customer wanted to have 3 flannel blankets that measured about 36" x 45", so she bought 6 pieces of flannel in one yard lengths. Every piece was cut like the picture below, some were cut as much as 4 inches off.

If I were to take the conservative approach and say the fabrics were cut only 2 inches off, that would still leave the blankets 2 inches shorter than expected once I cut the fabric straight.

Doing a little math, 6 fabrics times 2 inches means that 12 inches of fabric is wasted. In other words, my customer paid for 1/3 of a yard of fabric that ended up in the trash. I was a bit annoyed considering the current retail prices for fabric. Flannel runs about $6.99 a yard at Joann's which calculates out to about $2.31 in the garbage. And this is the conservative estimate.

Perhaps its not a huge loss. But it's still money in the trash.

I'm not sure if there is a way to avoid this problem. Just buy extra if you need to be sure and have a certain length. Do you have any similar examples?

This particular case was fairly egregious. My customer wanted to have 3 flannel blankets that measured about 36" x 45", so she bought 6 pieces of flannel in one yard lengths. Every piece was cut like the picture below, some were cut as much as 4 inches off.

If I were to take the conservative approach and say the fabrics were cut only 2 inches off, that would still leave the blankets 2 inches shorter than expected once I cut the fabric straight.

Doing a little math, 6 fabrics times 2 inches means that 12 inches of fabric is wasted. In other words, my customer paid for 1/3 of a yard of fabric that ended up in the trash. I was a bit annoyed considering the current retail prices for fabric. Flannel runs about $6.99 a yard at Joann's which calculates out to about $2.31 in the garbage. And this is the conservative estimate.

Perhaps its not a huge loss. But it's still money in the trash.

I'm not sure if there is a way to avoid this problem. Just buy extra if you need to be sure and have a certain length. Do you have any similar examples?

September 23, 2013

Repairing a leather sewing machine belt

If you own a sewing machine (industrial or otherwise) with a leather sewing machine belt, chances are that you will have to either replace or repair it at some point. Leather belts will stretch or shrink, and/or break. The climate of your workspace and other variables play into the life and condition of the belt. The area around the belt clip tends to get a lot of wear too. Leather belts are a little old school, but they do have a few advantages. They are customizable and relatively easy to fix.

You'll know you have a problem when the belt ends up in pieces or the machine is not operating properly. The leather belt on my Singer Hemstitcher 72w-19 machine stretched out over time and my machine was not going as fast as it should. It was time to shorten the belt.

Any workshop should have a toolbox. For this job, you'll need these tools:

One more note. There is a special tool designed to punch a hole in the leather belt for the belt clip. It's expensive. It doesn't work well (from what I'm told) and you don't need it. A drill with the right drill bit works really, really well.

In my case, I first removed the belt from the machine by bending the existing belt clip apart with pliers. You won't be able to reuse it, so don't bother trying to save it (this is why you want a box of 500!).

Next, determine how much to shorten the belt. It won't be as much as you think. If you make the belt too short, the belt won't fit or the belt will exert too much tension on the machine causing the machine to work harder than it should. Using the utility knife, I only shortened the belt 1/4".

About 1/4" from the cut end, drill a hole through the center of the belt. Be sure to drill the hole on top of some scrap wood so you don't damage your work table! You do need your other hand to help steady the belt as you drill, but I was taking a demo picture by myself. All other safe tool handling rules apply.

Place the belt clip through both holes to test, but don't mash the belt clip closed yet (Yes, I've done this!). Take the belt clip off one side and take the belt to the machine and thread it through the holes in the table. Attach the belt clip to the belt ends and place it over the handwheel and motor pulley to test the tension.

How much tension is needed? It depends on your machine. You need just enough to turn the handwheel properly. In the photo below I'm testing the tension (or slack) on the belt. This is about how much I need to have the machine operate properly.

Finally, mash the belt clip closed with the pliers (sometimes you need a hammer) and you're good to go. It's amazing that a 1/4" shorter in length makes a big difference!

You'll know you have a problem when the belt ends up in pieces or the machine is not operating properly. The leather belt on my Singer Hemstitcher 72w-19 machine stretched out over time and my machine was not going as fast as it should. It was time to shorten the belt.

Any workshop should have a toolbox. For this job, you'll need these tools:

- Drill

- 3/32nd drill bit

- Scrap wood

- Pliers

- Hammer

- Utility knife (not pictured)

- Belt clips (not pictured)

One more note. There is a special tool designed to punch a hole in the leather belt for the belt clip. It's expensive. It doesn't work well (from what I'm told) and you don't need it. A drill with the right drill bit works really, really well.

In my case, I first removed the belt from the machine by bending the existing belt clip apart with pliers. You won't be able to reuse it, so don't bother trying to save it (this is why you want a box of 500!).

Next, determine how much to shorten the belt. It won't be as much as you think. If you make the belt too short, the belt won't fit or the belt will exert too much tension on the machine causing the machine to work harder than it should. Using the utility knife, I only shortened the belt 1/4".

About 1/4" from the cut end, drill a hole through the center of the belt. Be sure to drill the hole on top of some scrap wood so you don't damage your work table! You do need your other hand to help steady the belt as you drill, but I was taking a demo picture by myself. All other safe tool handling rules apply.

Place the belt clip through both holes to test, but don't mash the belt clip closed yet (Yes, I've done this!). Take the belt clip off one side and take the belt to the machine and thread it through the holes in the table. Attach the belt clip to the belt ends and place it over the handwheel and motor pulley to test the tension.

How much tension is needed? It depends on your machine. You need just enough to turn the handwheel properly. In the photo below I'm testing the tension (or slack) on the belt. This is about how much I need to have the machine operate properly.

Finally, mash the belt clip closed with the pliers (sometimes you need a hammer) and you're good to go. It's amazing that a 1/4" shorter in length makes a big difference!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)