December 11, 2017

A new quilt project : Patches and Pinwheels

I have been following Bonnie Hunter for a few years and I finally decided to try one of her quilt patterns. I selected Patches and Pinwheels, one of her free patterns at her website. I wanted to try one of her quilt patterns because I wanted a feel for how she designs her quilts. I admire Bonnie's ability to sit down at a machine and sew scraps together to create a quilt - though I suspect she uses eQuilter design software more than we know. On the surface, this method of using fabric scraps in ready to go sizes seemed very relaxing. I also want to migrate into designing my own quilts. I know I can, but I get stuck at the planning stages. I needed to loosen up in my expectations of color and fabric and just play.

The fabric for this quilt comes mostly from upcycled men's shirts, but I threw a few of mine in there as well. With my first attempt, I did not pay attention to the fiber content of the shirts and some of them were more polyester then cotton. I ended up not liking the fabric from those shirts, so they ended up in the garbage - minus their buttons. After that I primarily used only cotton shirts. I supplemented with some shirts from the thrift store which yielded a surprising amount of fabric and a few fat quarters from the fabric store.

My first few attempts at cutting apart a man's shirt to harvest the fabric took me much longer than I expected. There is this little bit of fear about potentially ruining an otherwise good shirt. An irrational fear because several of these shirts had worn collars and cuffs and were not suitable for donation. After cutting down several, I developed a system and they went pretty fast.

The cutting and sewing went pretty well until I was ready to square up my blocks. The pinwheel blocks are fine for the most part. The 16 patch blocks were not. Bonnie Hunter recommends checking the piecing periodically to ensure everything measures as it should. I did not check very often. I figure my machine was set properly after the first few blocks and away I went. Come to find out that most of my 16-patch blocks all measured 1/4-3/8" too small. If the sewing or cutting is off just a little bit on a few of those 2 inch squares, the problem is quickly multiplied across the entire block.

So yes, I am going back through the 16-patch block and redoing them. This is a good lesson on precise cutting and sewing and checking measurements.

November 30, 2016

Hawaiian quilt pt. 2 and where I am now

On January 1, 2016, I finished piecing the Hawaiian quilt, complete with borders. It was an all day sewing marathon while I watched a Justice Network marathon (one of the few antenna based channels that comes in clear). Next up is to figure out the backing and then quilting. I plan on having a local quilter do the quilting, which is why this is still sitting here. Overall I am very happy with how this came together and when I finish it, I will post more pictures.

The thing I learned from this project was precision sewing. That crucial 1/4" seam allowance. I've read about it in many quilting books and tutorials and thought that I understood it. And then I discovered that my blocks did not measure up or match corresponding blocks. It wasn't terrible, but it was enough to bother me. I took the time to carefully square up each block, which included trimming the blocks down about an 1/8" so they were all the same size. The blocks are rotated 90 degrees, so there was really no need for the seams to match on corresponding blocks. Next time, I will pay more attention and check measurements as I go.

So why the long blog absence? It was really quite simple. I started working as a pattern maker again. It was a bit of a surprise opportunity to go back. At the same time I was dealing with a severe bout of chronic fatigue. So between the two jobs and the chronic fatigue, I had nothing left. I've been feeling better recently, though every now and then I'm reminded this is something I will have to deal with for a long time. I have a lot to say about how doctors treated me and what it took for me to recover, somewhat. But that is for another day and another blog.

In the meantime, I do want to get back to blogging. I will probably focus on whatever projects I am currently working on rather than pattern making and design. I have finished a few projects over the last year and a half, so there is more to come.

June 08, 2015

Hawaiian quilt pt. 1

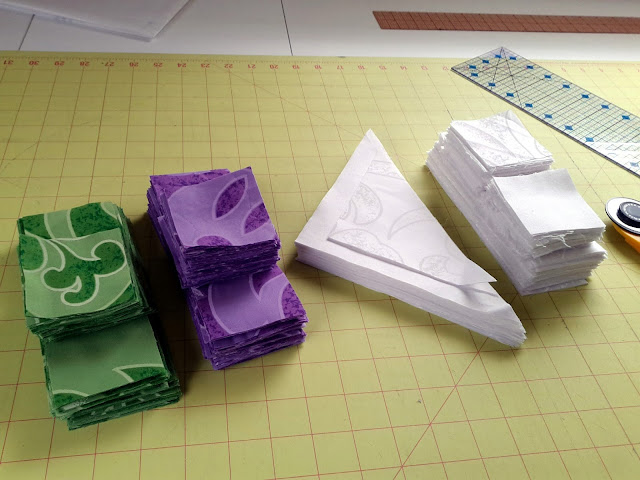

I started a quilt. The idea for this quilt has been floating around my head for a few years. I had some Hawaiian printed cottons left over from other projects and I wanted to use them in a modern style quilt. I have only three colors to work with, purple, green, and white. I had a hard time visualizing the overall look of the quilt, so I drew up a version using Inkscape*. I could have taken this a step further and scanned the fabric into the drawing, but this was close enough. I still have not decided on the final borders. It partially depends on how much of each color I have left after piecing the blocks. I'm fairly certain I will not be using green on the outside border. I may go for white instead with green bias binding.

Here are the actual fabrics, cut and ready to go.

The pattern came from Fat Quarter Fun

*Inkscape has some nifty drawing tools, including cloning. I did not use that feature here, but it would have been a perfect opportunity to use it.

May 26, 2015

Grading from body measurements pt. 3

This is part three of an ongoing discussion about N. A. Schofield's

article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. Part one

is here, part two here. I recommend reading the previous parts of this series before reading this one.

So what were the results of Schofield's experiment? I can't reproduce the actual results here, but it was something like this.

Imagine the square is a bodice pattern piece in one size. The star is supposed to be the same pattern piece but graded to the next size. Clearly, the two shapes have no proportional relationship to each other. The problem is further compounded by a different grade for corresponding pieces.

Imagine these are front and back bodice pattern pieces. Each corresponding pattern piece was graded separately based on the measurement data for that body location. Now imagine trying to sew the front and back together. It can't be done. Schofield freely admits the difficulty in the results. Though she also believes we need to learn how to deal with new shapes in pattern pieces in order to achieve superior fit.

Schofield's experiment left me with a lot of questions. I did not understand completely why she rejected the ASTM measurement data, nor why she went back to essentially raw data. Her grading methodology left me a bit confused. The results were clearly not suitable for industry application. Superior fit is the holy grail of fashion, but I'm not convinced that grading is the entire source of the problem. Superior fit, for each individual might only be achieved on an individual basis. In this case, 3D body scanning and customized clothing is the answer, but is it practical?

I would like to see this experiment repeated. The factors that will impact additional experiments are the measurement data and grading methodology. Why not use ASTM measurement data? Why not use traditional grading methods? I always support those who are willing to test ideas and theories. This was a worthy attempt by Schofield to ask important why and how questions.

So what were the results of Schofield's experiment? I can't reproduce the actual results here, but it was something like this.

Imagine the square is a bodice pattern piece in one size. The star is supposed to be the same pattern piece but graded to the next size. Clearly, the two shapes have no proportional relationship to each other. The problem is further compounded by a different grade for corresponding pieces.

Imagine these are front and back bodice pattern pieces. Each corresponding pattern piece was graded separately based on the measurement data for that body location. Now imagine trying to sew the front and back together. It can't be done. Schofield freely admits the difficulty in the results. Though she also believes we need to learn how to deal with new shapes in pattern pieces in order to achieve superior fit.

Schofield's experiment left me with a lot of questions. I did not understand completely why she rejected the ASTM measurement data, nor why she went back to essentially raw data. Her grading methodology left me a bit confused. The results were clearly not suitable for industry application. Superior fit is the holy grail of fashion, but I'm not convinced that grading is the entire source of the problem. Superior fit, for each individual might only be achieved on an individual basis. In this case, 3D body scanning and customized clothing is the answer, but is it practical?

I would like to see this experiment repeated. The factors that will impact additional experiments are the measurement data and grading methodology. Why not use ASTM measurement data? Why not use traditional grading methods? I always support those who are willing to test ideas and theories. This was a worthy attempt by Schofield to ask important why and how questions.

April 16, 2015

Grading from body measurements pt. 2

This is part two of an ongoing discussion about N. A. Schofield's article Pattern Grading found in the Sizing in Clothing book. Part one is here.

My initial reaction to the idea of grading from body measurements was, "Well, of course we should." And in fact, we do for children's clothing. It seemed rather obvious to me to look at children's clothing as a model. Children's sizing is based on the idea of growth, meaning that the measurement intervals between sizes are not always consistent.

Let's look at an example for a 4-6x size range.*

For sizes 4, 5, 6, 6x

Chest: 23, 24, 25, 25.5

Waist: 21.5, 22, 22.5, 23

Hip: 23.5, 24.5, 25.5, 26.5

The grade works out to be, choosing size 5 as the base size:

Chest: 1, 0, 1, 1.5

Waist: 0.5, 0, 0.5, 0.5

Hip: 1, 0, 1, 1

In this example, we have a 1" chest grade, except for size 6x which is 1.5". The waist is a 0.5" inch grade and the hip returns to a 1" grade for all sizes. Each body measurement area has it's own grade.

In women's clothing a 2" grade means that the interval change between the sizes will be 2" for chest, waist, and hips. Though even this isn't true across all brands, and you will find variations. (IMO, this is a good thing)

I don't know the history of women's sizing well enough to explain how this mode of practice came to be nor exactly why. It is clear that it does make grading, especially hand grading, much easier in practice. It is also unclear to me that grading is the source of our fitting woes. Nevertheless, it does make sense to me to go back and look at body measurements and devise a more precise grade rule.

The question then becomes, which body measurements do we use? In my children's example above, the numbers are still nice and easy to work with. The body measurements have been intentionally manipulated to be easy to work with. Raw measurement data was averaged, sorted, and studied to arrive at some numbers. Those numbers were not easy to work with, so a group of industry professionals sat down and made them that way. They modified certain measurements by about 1/8" to achieve consistency. Their modifications were rather minor and easily fall within a statistical margin of error. If you read their reasoning, it makes sense. This manipulation of measurement data for ease of use continues today in more modern measurement studies. It seems deceitful, but at the end of the day is infinitely practical. ASTM D4910 inherits this method of data handling from the measurement studies done in the 1940s, but does provide some updated measurements.

Looking at the Misses body measurement chart, ASTM D5585, it seems to be arranged and handled in the same way as the children's body measurement chart. IOW, the chart does not show a 1, 1.5, or 2 inch grade in the body measurements. It is a lot like the children's example above. There does seem to be a disconnect between measurement data and grading, at least on the surface. Individual companies will decide how to interpret and implement measurement data, and therefore their grade rules. (IMO, I think this is a good thing). And some will use a 2 inch grade, and some will not.

So what measurement data did Schofield use? She rejected the ASTM charts and created her own version of measurements derived from body measurement studies. This presented a problem because measurement studies do not always include the measurements needed for pattern making and grading. Schofield did not normalize the data, in other words make it easy to work with. Also she had to figure out how to deal with missing measurement data. I no longer have a copy of the article and can't look back, but Schofield selected certain measurements over others. How and why she handled those measurements puzzled me.

I believe Schofield's goal was to remove the idea of maintaining an ideal proportion or predictable pattern shape. She wanted to see what the body measurements really did between sizes.

Her results were almost predictable. More on that later.

*These measurements come from the withdrawn child measurement standard CS151-50. Measurements are in inches.

My initial reaction to the idea of grading from body measurements was, "Well, of course we should." And in fact, we do for children's clothing. It seemed rather obvious to me to look at children's clothing as a model. Children's sizing is based on the idea of growth, meaning that the measurement intervals between sizes are not always consistent.

Let's look at an example for a 4-6x size range.*

For sizes 4, 5, 6, 6x

Chest: 23, 24, 25, 25.5

Waist: 21.5, 22, 22.5, 23

Hip: 23.5, 24.5, 25.5, 26.5

The grade works out to be, choosing size 5 as the base size:

Chest: 1, 0, 1, 1.5

Waist: 0.5, 0, 0.5, 0.5

Hip: 1, 0, 1, 1

In this example, we have a 1" chest grade, except for size 6x which is 1.5". The waist is a 0.5" inch grade and the hip returns to a 1" grade for all sizes. Each body measurement area has it's own grade.

In women's clothing a 2" grade means that the interval change between the sizes will be 2" for chest, waist, and hips. Though even this isn't true across all brands, and you will find variations. (IMO, this is a good thing)

I don't know the history of women's sizing well enough to explain how this mode of practice came to be nor exactly why. It is clear that it does make grading, especially hand grading, much easier in practice. It is also unclear to me that grading is the source of our fitting woes. Nevertheless, it does make sense to me to go back and look at body measurements and devise a more precise grade rule.

The question then becomes, which body measurements do we use? In my children's example above, the numbers are still nice and easy to work with. The body measurements have been intentionally manipulated to be easy to work with. Raw measurement data was averaged, sorted, and studied to arrive at some numbers. Those numbers were not easy to work with, so a group of industry professionals sat down and made them that way. They modified certain measurements by about 1/8" to achieve consistency. Their modifications were rather minor and easily fall within a statistical margin of error. If you read their reasoning, it makes sense. This manipulation of measurement data for ease of use continues today in more modern measurement studies. It seems deceitful, but at the end of the day is infinitely practical. ASTM D4910 inherits this method of data handling from the measurement studies done in the 1940s, but does provide some updated measurements.

Looking at the Misses body measurement chart, ASTM D5585, it seems to be arranged and handled in the same way as the children's body measurement chart. IOW, the chart does not show a 1, 1.5, or 2 inch grade in the body measurements. It is a lot like the children's example above. There does seem to be a disconnect between measurement data and grading, at least on the surface. Individual companies will decide how to interpret and implement measurement data, and therefore their grade rules. (IMO, I think this is a good thing). And some will use a 2 inch grade, and some will not.

So what measurement data did Schofield use? She rejected the ASTM charts and created her own version of measurements derived from body measurement studies. This presented a problem because measurement studies do not always include the measurements needed for pattern making and grading. Schofield did not normalize the data, in other words make it easy to work with. Also she had to figure out how to deal with missing measurement data. I no longer have a copy of the article and can't look back, but Schofield selected certain measurements over others. How and why she handled those measurements puzzled me.

I believe Schofield's goal was to remove the idea of maintaining an ideal proportion or predictable pattern shape. She wanted to see what the body measurements really did between sizes.

Her results were almost predictable. More on that later.

*These measurements come from the withdrawn child measurement standard CS151-50. Measurements are in inches.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)