Anyway, I have tried to put the theory into practice and I have made some progress. I only offer my styles in sizes 3M to 6x. I am still working on the grades for the 4-6x styles, so I am nearly there. My sizes break down like this:

3M, 6M, 9M*, 12M, 18M

24M/2T, 3T, 4T/4

5, 6, 6x

I don't really consider the 9M as a true size. It is a half size between the 6M and 12M and is graded by splitting the grade between the 6M and 12M. The 24M and 2T are essentially the same as are the 4T and 4 - those sizes have been combined for grading purposes. My website still delineates the combined sizes as separate sizes.

This blog entry is not a discussion on the why and wherefores of children's sizing - a surprisingly complex and controversial topic. Instead, I wanted to show a possible grading/pattern problem that shows up now and then. I have been grading and comparing my basic bodice blocks. You should do this too because someone will eventually see the problem and it will be more difficult to fix.

I have drafted my basic bodice block three times, in each of my sample sizes for each of my size ranges - 12M, 3T, 5. (BTW, you can't use the same pattern piece and grade it in all the sizes. Believe me, that is one large headache). The next step is to grade each range separately. Keep in mind that each sample size will have slightly different shaping, but the general shape and proportion should be related.

Before getting too far, the outer fringes of each size range should be compared. For example, the size 18M should be smaller than the 24M/2T and the size 4T/4 should be smaller than the 5. Originally, I had graded the size 4T and 4 separately. In other words the 4T was based off the 3T sample and the 4 was based off the 5. The reason I combined the 4T and 4 was because the shape and overall size was so similar it was a duplication in effort, and I also ran into the problem where the 4T was actually larger than the 4. If you do separate out the sizes than the 4T must be smaller than the 4. If you don't check your grades, someone will bring two dresses to you and say the patterns are wrong, size labels are switched or some other problem.

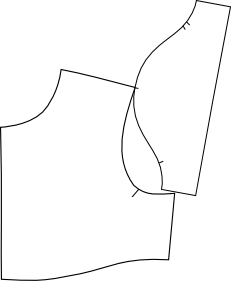

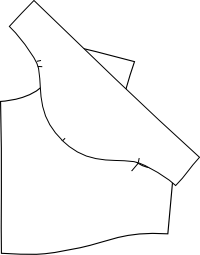

In the photos below you can see the problem more clearly. In the top picture, the size 4 is laying on top of the 4T. You can see the 4 is smaller than the 4T. In the bottom picture the 4T is on top of the 4 and it is clearly longer with a larger armhole.

To solve this problem, I have been reworking my toddler patterns. I started by combining sizes 4T and 4 so I have one less size to grade. Next my toddler bodices were redrafted to have a shape similar to the 5 (less boxy, smaller armhole). Finally, I regraded the toddler patterns. This is still a work in progress, but the results are much better - each size is progressively larger.

I had the same problem with my size 18M and 24M/2T. In this case it wasn't a grading problem. Instead my infant patterns were proportionally too long compared to the toddler. I fixed this by shortening the bodice slightly.

Anyway, the point is that you should make sure and check the sizes on the outer fringes of each size range and make adjustments so that each size is progressively larger. You can adjust the grade rules (much easier in CAD, btw) or change the shape of the patterns.

(I am ignoring the idea that in the real world an 18M child could be larger than a 24M child. If that is the case, a parent would buy a larger size than 18M and just complain about the craziness of US sizing standards. When I did private label programs for the big box retailers their grade/POM charts progressively got larger with each size. Logically it makes sense even if reality is very different. Anyway, you can allow your sizes to overlap if you want, you'll just need to have an explanation as to why when a sewing contractor becomes confused.).